by Michael Liss

How do you feel about an Imperial Presidency?

Attorney General William Barr has been on a bit of a bender recently. He’s suggested that communities that are critical of law enforcement will lose police protection, disagreed with the Inspector General’s report about the FBI and the Russia investigation, and warmed the hearts of the faithful at Notre Dame in decrying a “war on religion.”

While Mr. Barr rarely fails to make news, his most consequential opinions came in a speech he gave to the Federalist Society on November 15, 2019, in which he went on, at some length, as to why he supports the broadest possible interpretation of Presidential powers.

If you have read reports about Mr. Barr’s remarks, you probably already know they have been criticized for their ferocious partisanship. There is unquestionably a considerable amount of energy devoted to critiquing those who get in President Trump’s way (Congress, the federal courts, Progressives, and private citizens who exercise their right of free speech). But Mr. Barr is not only a man of intensity, he is also one of words (over 6000 here), and, when moved to talk about substance, he has a lot to say. You can find the text on the Department of Justice website.

If you have read reports about Mr. Barr’s remarks, you probably already know they have been criticized for their ferocious partisanship. There is unquestionably a considerable amount of energy devoted to critiquing those who get in President Trump’s way (Congress, the federal courts, Progressives, and private citizens who exercise their right of free speech). But Mr. Barr is not only a man of intensity, he is also one of words (over 6000 here), and, when moved to talk about substance, he has a lot to say. You can find the text on the Department of Justice website.

It’s pointless to argue with Barr about his personal political views, regardless of the tone in which they are delivered. And it’s shouting into gale-force winds to note that his zeal for an uber-powerful Presidency seems to wax and wane depending on the party identification of the person occupying the Oval Office. What is interesting, and important, is reviewing the customized version of history that leads him to take his present view of both Presidential power and the nature of the relationships among the three branches of government.

His first dive into the past is a fascinating one:

The grammar school civics class version of our Revolution is that it was a rebellion against monarchial tyranny, and that, in framing our Constitution, one of the main preoccupations of the Founders was to keep the Executive weak. This is misguided. By the time of the Glorious Revolution of 1689, monarchical power was effectively neutered and had begun its steady decline. Parliamentary power was well on its way to supremacy and was effectively in the driver’s seat. By the time of the American Revolution, the patriots well understood that their prime antagonist was an overweening Parliament. Indeed, British thinkers came to conceive of Parliament, rather than the people, as the seat of Sovereignty.

I went to grammar school, and I think this is a very clever argument, albeit completely misleading. He’s conflated two separate thoughts—a debatable one that the colonists were not rejecting a strong executive, with an unsupported one that “patriots well understood that their prime antagonist was an overweening Parliament.” And he’s forgotten that Parliament was not some malevolent jellyfish made up of a thousand stinging MPs and Lords. They, too, had Executive leadership—a Cabinet and a Prime Minister (Lord North, during most of the Revolutionary War whom, ironically, 19th Century historians judged too subservient to the King).

What most of the colonists opposed, and what caused them to revolt, was authoritarianism, regardless of the package in which it came. They did not reject the authority of Parliament in order to embrace King George III, and, by extension, did not see an all-powerful Executive as a desirable alternative to an all-powerful legislature. As Jefferson put it in the Declaration of Independence, “[a] Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.” The men who signed the Declaration were asserting their aspiration to be free of government by fiat, free of government without representation. That’s what British rule meant to them.

Jefferson’s words are the poetry of that aspiration, but we don’t necessarily need to look deeply into his writings or those of the other Founders to deduce this—we also can judge it from conduct. The newly independent states did not leap into a complex and binding contract including a powerful Chief Executive. Instead, they opted for the Articles of Confederation, which had no Chief Executive at all. Given a first choice of governing schemes, men of property and influence (the only folks who counted) chose the loosest form of alliance. The reasons for this were many—but the most prominent had to be the unwillingness to cede local control to a larger entity in which they would risk losing influence. The once-colonists saw themselves more as citizens of the individual States, and not the United States.

Barr asserts that

American thinkers who considered inaugurating a republican form of government tended to think of the Executive component as essentially an errand boy of a Supreme legislative branch. Often the Executive (sometimes constituted as a multi-member council) was conceived as a creature of the Legislature, dependent on and subservient to that body, whose sole function was carrying out the Legislative will.

Again, this is only partially true. American aristocracy surely preferred to rule, rather than to be ruled, and Benjamin Franklin, for example, had a miserable time as the largely figurehead Governor of Pennsylvania. But New York’s Governor George Clinton, on the other hand, had a tight fist on power, and Virginia’s Governor from 1784-86 was the formidable Patrick Henry (who was later to lead the opposition to the ratification of the new Constitution).

Barr’s conclusion is that the failures of the Articles of Confederation were simply a result of a lack of Executive authority: “They had seen that the War had almost been lost and was a bumbling enterprise because of the lack of strong Executive leadership.” Again, he’s conflating two things. The management of the War was a bumbling enterprise, but it was a bumbling enterprise because of both a lack of a strong Executive and an overall lack of a strong federal government. It’s telling that Barr doesn’t acknowledge the contradiction in his own position: The most powerful nation in the world at that time was England—the very same country he previously derided as being in the hands of a Parliament with a figurehead King as Chief Executive.

The Articles failed for any number of prosaic reasons. No one took the new nation seriously, and there was little reason to do so. Thirteen states loosely tied together, each exercising a considerable amount of autonomy, and, in effect, possessing veto power over national policy, were inadequate to the challenges of building a new nation surrounded by hostile powers. The British, despite having signed the Treaty of Paris four years earlier to end the War of Independence, never quite reconciled themselves to the idea of leaving, and there were forts where the disembarkation process seemed particularly slow. States were fighting over boundaries; no one was collecting taxes; the new nation’s currency was a largely worthless script; and trade was a tangle of often inward-directed tariffs and preferences.

Many (not all) of the leaders of the Revolution knew there had to be change, but Barr is careless in implying that the choice was obvious, was acknowledged by a broad consensus, and was primarily tied to the lack of a strong Chief Executive.

In fact, there was nothing even approaching unanimity that the Articles should be abandoned. An effort to tinker with them crashed and burned at Annapolis when only five states (and just 12 men) showed up. Things were sufficiently delicate that even the phrase “Constitutional Convention” was too much for many, so the folks with the figurative wrecking ball (Madison, Adams, Hamilton, Franklin, John Jay, and, quietly, George Washington), had to tip-toe up to it by insisting, in effect, that they were just replacing the shutters and doing a fresh paint-job. It is only after they all assembled in Philadelphia, and Virginia sprung its complex and far-reaching “Virginia Plan,” that many of the delegates realized the true purpose of the meeting. Not all were happy about it.

I don’t want to fall into the trap of misstating history just to show Barr does the same. There was substantial support from many of the attendees for change, and that change included a Chief Executive with a job description that went beyond sinecure. Where he and I differ is the Framers’ understanding of the scope of Presidential authority.

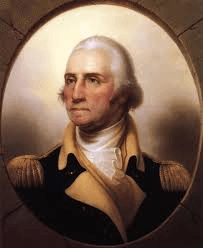

From my perspective, you have to give great weight to the centrality of George Washington to the entire debate. This is not because of anything he wrote (not a word of the Constitution was penned by him), nor because of anything he said during the Convention (he was a literally silent Chair). Rather, it was because he was the Indispensable Man. In 1787, before political parties, and before Washington actually had a governing record as President to gripe about, people judged him on his service to the fledgling nation, which was considered unsurpassed. They saw him as incorruptible, above politics, and honor-bound to duty. His motives were never in question.

We can be certain that the mostly high-born and influential attendees might have had a slightly more skeptical view, but it was irrelevant. Every single one of them knew the public believed in Washington’s near demi-god status, and that Washington’s blessing was needed for a new form of government. He had taken the first step by supporting a Constitutional Convention and becoming its Chair. Would he take the second by throwing his weight in favor of the finished product?

This created a fascinating dynamic in the drafting and debate when the conversation turned to a Chief Executive. Washington wasn’t going to agree to any role that lacked substance. This wasn’t just a matter of pride. Washington prized his life at Mount Vernon and felt he had to fulfill his pledge to emulate the Roman General Cincinnatus and retire (permanently) to private life. He also had an acute sense of his own mortality. The Washington men didn’t survive past their 50s, and, by the time of the Convention, he was already 55. Only a call to a higher duty could lure him.

In short, the job had to be a big one. And, to complicate things further, the debate and the negotiations literally had to take place in front of his eyes. Things could get tense. If the new form of government was to have an Executive, and that job were to have the legitimacy in the public’s eyes that Barr insisted that Governors lacked, it had to be affirmed by Washington. Washington’s acceptance of the Presidency gave it the prestige it needed, and by extension, lent that prestige to the entire new governing scheme.

All that being said, the attendees weren’t there just to satisfy Washington, and the adoption of a vibrant Chief Executive wasn’t a universal panacea. A new government meant a complex rearrangement of power among the States, among regions, and between the government and its citizens. There were at least four points of view represented at the Convention and in the 13 States. Some believed the Articles were perfectly fine: They liked the autonomy it afforded their States (and the power it gave to the aristocracy in those States) and were loath to give it up. The importance of this group became even more apparent during the ratification stage. Others accepted the idea that a new government was needed, with an Executive office, but not a new strong Executive—whatever powers the nominal head of state might have would be substantially circumscribed by a Legislature that would dominate, and it was the makeup of that Legislature (one house or two, proportional representation or not) that concerned them more. The third group conceived of an Executive closer to the type of Presidency we have today. The fourth’s views might be found both in Madison’s original construct, which included a Presidential veto of State laws, and in the extraordinary speech at the Convention given by Hamilton, who literally proposed a President for Life.

Obviously, Washington would never have gone for either a continuation of the Articles or a largely ceremonial Presidency. But, if the debate were to advance to a newer form of government with a stronger Chief Executive another problem would have to be addressed: Washington himself could be trusted with authority, but his successor was an unknown. Making the job big enough for Washington to accept would, at minimum, potentially endow it with more power than the Convention would have been comfortable giving to a lesser man. So, if we are to divine the Framers’ intent as to the extent of Presidential power, we should accept that the text of the Constitution is the boundary. That is the most that the Framers were willing to grant (and the States willing to ratify) to even Washington—and that, only after a Bill of Rights was attached. If Barr is floating, as the Framers’ idea, an all-powerful-yet-benevolent-tribune-of-the-people President, then he’s spinning it out of whole cloth. That construct is not supported by the text of the Constitution (or The Federalist Papers), or by contemporaneous behavior. What the Framers agreed to and wrote, and what the States subsequently ratified, is what they meant, not less, but not more. Any broader assertion of Presidential power than exceeds that original grant of authority to Washington (and his successors) has to be defended on other grounds.

You may not be surprised that William Barr has a plan for that. That’s a different battle, and I”ll take it up on another day.