by Emrys Westacott

In Homo Deus, the 2017 follow-up to his widely read Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari dismisses the idea of free will in cavalier fashion. Contemporary science, he argues, has proved it to be a fiction. In support of this claim, he offers several arguments.

In Homo Deus, the 2017 follow-up to his widely read Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari dismisses the idea of free will in cavalier fashion. Contemporary science, he argues, has proved it to be a fiction. In support of this claim, he offers several arguments.

- Everything we do is fully determined by our “genes, hormones, and neurons,” and these “obey the same physical and chemical laws governing the rest of reality.” So from a scientific point of view, if we ask why a man performed any act, “answering ‘Because he chose to’ doesn’t cut the mustard. Instead, geneticists and brain scientists provide a much more detailed answer: ‘He did it due to such-and-such electro-chemical processes in the brain that were shaped by a particular genetic make-up, which in turn reflect evolutionary pressures coupled with random mutations.”[1]

- The concept of free will is incompatible with the theory of evolution. According to Darwin’s theory, we came to be what we are by passing on genes that proved useful in the struggle to survive. If human actions (e.g. eating and mating) were freely chosen, then we couldn’t explain our evolution in terms of natural selection.

- Recent laboratory research proves that our feeling that we make free choices is an illusion. Subjects whose brains are being monitored are told to press one of two switches. They think they are making a free choice; but a scientist watching a brain scanner can predict which switch they will press before the subject is even aware of having made a choice. This shows, says Harari, that “I don’t choose my desires. I only feel them, and act accordingly.”[2]

- The idea of free will is bound up with the idea of an individual self that constitutes the inner essence of each human being. This modern notion of the self is really just a hangover from the religious concept of the soul. But all these notions–soul, self, essence–are outmoded; “so to ask, ‘How does the self choose its desires?’ …[is] like asking a bachelor, ‘How does your wife choose her clothes?’ In reality there is only a stream of consciousness, and desires arise and pass away within this stream, but there is no permanent self that owns the desires…”[3]

Harari advances these arguments with great confidence. Yet they are far from conclusive. Read more »

Once upon a time, in a beautiful but endangered forest far far away a prince and princess met, fell in love and married. They were blessed with a hundred children. “I wonder,” said the princess, somewhat exhausted from her exertions, “how best to raise our dear ones to care for each other and their beautiful forest home?” “I have heard,” replied her husband “that reading to children matters.”

Once upon a time, in a beautiful but endangered forest far far away a prince and princess met, fell in love and married. They were blessed with a hundred children. “I wonder,” said the princess, somewhat exhausted from her exertions, “how best to raise our dear ones to care for each other and their beautiful forest home?” “I have heard,” replied her husband “that reading to children matters.”

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

I was always a skinny fuck. Forever the thinnest kid in the class, and for a longtime the second shortest boy (thank you, David Mehler). My stick-figure proportions were the thing of legend. I could suck my stomach in so far that some people swore they could touch the inside of my spine. My uncle used to refer to me as the Biafra Boy, a tasteless reference to the gruesome famine that accompanied the Nigerian Civil War (1967 – 70). In an effort to fatten me up, my grandmother would serve me breakfast cereal with half-and-half instead of milk. It was to no avail. A growth spurt in the 8th grade got me well above the short kids, but my body didn’t fill out. I graduated high school standing five feet, nine and a half inches tall, and weighing less than 120 pounds.

I was always a skinny fuck. Forever the thinnest kid in the class, and for a longtime the second shortest boy (thank you, David Mehler). My stick-figure proportions were the thing of legend. I could suck my stomach in so far that some people swore they could touch the inside of my spine. My uncle used to refer to me as the Biafra Boy, a tasteless reference to the gruesome famine that accompanied the Nigerian Civil War (1967 – 70). In an effort to fatten me up, my grandmother would serve me breakfast cereal with half-and-half instead of milk. It was to no avail. A growth spurt in the 8th grade got me well above the short kids, but my body didn’t fill out. I graduated high school standing five feet, nine and a half inches tall, and weighing less than 120 pounds.

It is indeed supremely difficult to effectively refute the claim that John von Neumann is likely the most intelligent person who has ever lived. By the time of his death in 1957 at the modest age of 53, the Hungarian polymath had not only revolutionized several subfields of mathematics and physics but also made foundational contributions to pure economics and statistics and taken key parts in the invention of the atomic bomb, nuclear energy and digital computing.

It is indeed supremely difficult to effectively refute the claim that John von Neumann is likely the most intelligent person who has ever lived. By the time of his death in 1957 at the modest age of 53, the Hungarian polymath had not only revolutionized several subfields of mathematics and physics but also made foundational contributions to pure economics and statistics and taken key parts in the invention of the atomic bomb, nuclear energy and digital computing. After the 2008 election, the New Yorker’s Ryan Lizza reported that Obama had told his incoming political director, Patrick Gaspard, “I think that I’m a better speechwriter than my speechwriters. I know more about policies on any particular issue than my policy directors. And I’ll tell you right now that I’m going to think I’m a better political director than my political director.”

After the 2008 election, the New Yorker’s Ryan Lizza reported that Obama had told his incoming political director, Patrick Gaspard, “I think that I’m a better speechwriter than my speechwriters. I know more about policies on any particular issue than my policy directors. And I’ll tell you right now that I’m going to think I’m a better political director than my political director.” President Trump has far surpassed Nixon in his zeal to ignore, jettison or rewrite the nation’s norms. Even his allies in the Republican Party, in which Trump still has

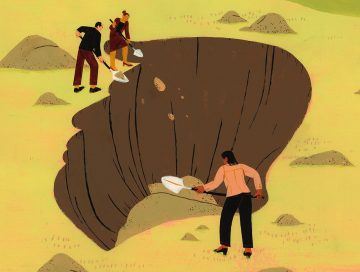

President Trump has far surpassed Nixon in his zeal to ignore, jettison or rewrite the nation’s norms. Even his allies in the Republican Party, in which Trump still has  The hero of Thomas Hardy’s tragic novel Jude the Obscure (1895) is a poor stonemason living in a Victorian village who is desperate to study Latin and Greek at university. He gazes, from the top of a ladder leaning against a rural barn, on the spires of the University of Christminster (a fictional substitute for Oxford). The spires, vanes and domes ‘like the topaz gleamed’ in the distance. The lustrous topaz shares its golden colour with the stone used to build Oxbridge colleges, but it is also one of the hardest minerals in nature. Jude’s fragile psyche and health inevitably collapse when he discovers just how unbreakable are the social barriers that exclude him from elite culture and perpetuate his class position, however lovely the buildings seem that concretely represent them, shimmering on the horizon. By Hardy’s time, the trope of the exclusion of the working class from the classical cultural realm, especially from access to the ancient languages, had become a standard feature of British fiction. Charles Dickens probes the class system with a tragicomic scalpel in David Copperfield (1850). The envious Uriah sees David as a privileged young snob, but he refuses to accept the offer of Latin lessons because he is ‘far too umble. There are people enough to tread upon me in my lowly state, without my doing outrage to their feelings by possessing learning.’

The hero of Thomas Hardy’s tragic novel Jude the Obscure (1895) is a poor stonemason living in a Victorian village who is desperate to study Latin and Greek at university. He gazes, from the top of a ladder leaning against a rural barn, on the spires of the University of Christminster (a fictional substitute for Oxford). The spires, vanes and domes ‘like the topaz gleamed’ in the distance. The lustrous topaz shares its golden colour with the stone used to build Oxbridge colleges, but it is also one of the hardest minerals in nature. Jude’s fragile psyche and health inevitably collapse when he discovers just how unbreakable are the social barriers that exclude him from elite culture and perpetuate his class position, however lovely the buildings seem that concretely represent them, shimmering on the horizon. By Hardy’s time, the trope of the exclusion of the working class from the classical cultural realm, especially from access to the ancient languages, had become a standard feature of British fiction. Charles Dickens probes the class system with a tragicomic scalpel in David Copperfield (1850). The envious Uriah sees David as a privileged young snob, but he refuses to accept the offer of Latin lessons because he is ‘far too umble. There are people enough to tread upon me in my lowly state, without my doing outrage to their feelings by possessing learning.’ Democracy depends

Democracy depends