Gaia Vince in The Guardian:

Fathers are happier, less stressed and less tired than mothers, finds a study from the American Time Use Survey. Not unrelated, surely, is the regular report that mothers do more housework and childcare than fathers, even when both parents work full time. When the primary breadwinner is the mother versus the father, she also shoulders the mental load of family management, being three times more likely to handle and schedule their activities, appointments, holidays and gatherings, organise the family finances and take care of home maintenance, according to Slate, the US website. (Men, incidentally, are twice as likely as women to think household chores are divided equally.) In spite of their outsized contributions, full-time working mothers also feel more guilt than full-time working fathers about the negative impact on their children of working. One argument that is often used to explain the anxiety that working mothers experience is that it – and many other social ills – is the result of men and women not living “as nature intended”. This school of thought suggests that men are naturally the dominant ones, whereas women are naturally homemakers.

Fathers are happier, less stressed and less tired than mothers, finds a study from the American Time Use Survey. Not unrelated, surely, is the regular report that mothers do more housework and childcare than fathers, even when both parents work full time. When the primary breadwinner is the mother versus the father, she also shoulders the mental load of family management, being three times more likely to handle and schedule their activities, appointments, holidays and gatherings, organise the family finances and take care of home maintenance, according to Slate, the US website. (Men, incidentally, are twice as likely as women to think household chores are divided equally.) In spite of their outsized contributions, full-time working mothers also feel more guilt than full-time working fathers about the negative impact on their children of working. One argument that is often used to explain the anxiety that working mothers experience is that it – and many other social ills – is the result of men and women not living “as nature intended”. This school of thought suggests that men are naturally the dominant ones, whereas women are naturally homemakers.

But the patriarchy is not the “natural” human state. It is, though, very real, often a question of life or death. At least 126 million women and girls around the world are “missing” due to sex-selective abortions, infanticide or neglect, according to United Nations Population Fund figures. Women in some countries have so little power they are essentially infantilised, unable to travel, drive, even show their faces, without male permission. In Britain, with its equality legislation, two women are killed each week by a male partner, and the violence begins in girlhood: it was reported last month that one in 16 US girls was forced into their first experience of sex. The best-paid jobs are mainly held by men; the unpaid labour mainly falls to women. Globally, 82% of ministerial positions are held by men. Whole fields of expertise are predominantly male, such as physical sciences (and women garner less recognition for their contributions – they have received just 2.77% of the Nobel prizes for sciences).

More here.

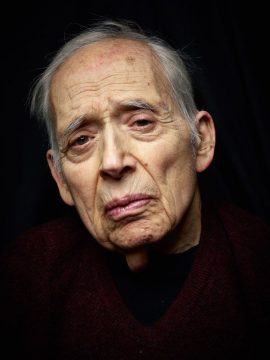

Had she not died at 27 of an accidental heroin overdose, Janis Joplin would be 76 — two years younger than Paul Simon and four years younger than Mavis Staples. Singers with scorched voices sometimes settle more deeply into them. (Have you heard the most recent Marianne Faithfull album?) One wonders at the body of recordings Joplin might have made.

Had she not died at 27 of an accidental heroin overdose, Janis Joplin would be 76 — two years younger than Paul Simon and four years younger than Mavis Staples. Singers with scorched voices sometimes settle more deeply into them. (Have you heard the most recent Marianne Faithfull album?) One wonders at the body of recordings Joplin might have made.

Farwell’s music would lose many of these Romantic characteristics after his first journey to the West, undertaken in the autumn of 1903. He explored pueblos and Indian reservations, gazing in wonder at the sublime beauty of the desert—to Farwell, a love of Native American cultures was inseparable from a veneration of the land. Indeed, his first sight of the Grand Canyon put him in a rapturous state: “I sat there watching the lights and shadows play and change over the strange distances and depths of this wonderworld,” he later recalled, “and heard the unwritten symphonies of the ages past and the ages to come.” (Half a century later, the Sonoran Desert would similarly inspire Elliott Carter, who came away from a year’s sojourn in Arizona with one of his first masterpieces, the String Quartet No. 1.)

Farwell’s music would lose many of these Romantic characteristics after his first journey to the West, undertaken in the autumn of 1903. He explored pueblos and Indian reservations, gazing in wonder at the sublime beauty of the desert—to Farwell, a love of Native American cultures was inseparable from a veneration of the land. Indeed, his first sight of the Grand Canyon put him in a rapturous state: “I sat there watching the lights and shadows play and change over the strange distances and depths of this wonderworld,” he later recalled, “and heard the unwritten symphonies of the ages past and the ages to come.” (Half a century later, the Sonoran Desert would similarly inspire Elliott Carter, who came away from a year’s sojourn in Arizona with one of his first masterpieces, the String Quartet No. 1.) Adam Tooze in Foreign Policy:

Adam Tooze in Foreign Policy: Isaac Stanley in openDemocracy:

Isaac Stanley in openDemocracy: Jeffrey Fleishman in the LA Times:

Jeffrey Fleishman in the LA Times: Fathers are happier, less stressed and less tired than mothers, finds a study from the American Time Use Survey. Not unrelated, surely, is the regular report that mothers do more housework and childcare than fathers, even when both parents work full time. When the primary breadwinner is the mother versus the father, she also shoulders the mental load of family management, being three times more likely to handle and schedule their activities, appointments, holidays and gatherings, organise the family finances and take care of home maintenance, according to Slate, the US website. (Men, incidentally, are twice as likely as women to think household chores are divided equally.) In spite of their outsized contributions, full-time working mothers also feel more guilt than full-time working fathers about the negative impact on their children of working. One argument that is often used to explain the anxiety that working mothers experience is that it – and many other social ills – is the result of men and women not living “as nature intended”. This school of thought suggests that men are naturally the dominant ones, whereas women are naturally homemakers.

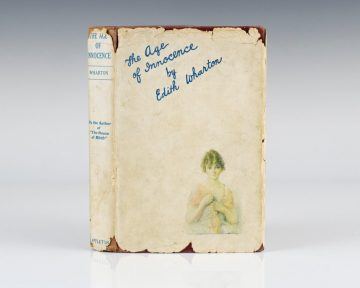

Fathers are happier, less stressed and less tired than mothers, finds a study from the American Time Use Survey. Not unrelated, surely, is the regular report that mothers do more housework and childcare than fathers, even when both parents work full time. When the primary breadwinner is the mother versus the father, she also shoulders the mental load of family management, being three times more likely to handle and schedule their activities, appointments, holidays and gatherings, organise the family finances and take care of home maintenance, according to Slate, the US website. (Men, incidentally, are twice as likely as women to think household chores are divided equally.) In spite of their outsized contributions, full-time working mothers also feel more guilt than full-time working fathers about the negative impact on their children of working. One argument that is often used to explain the anxiety that working mothers experience is that it – and many other social ills – is the result of men and women not living “as nature intended”. This school of thought suggests that men are naturally the dominant ones, whereas women are naturally homemakers. A literary “classic” is a recurring character in one’s life. One reads it, years go by, one reads it again, and it becomes the sum of those readings over time. One identifies with the character closest to one in age — and then one’s age changes. Eventually, each classic tells two stories: its own, and the story of all the times one has read it. In a way, in “The Age of Innocence,” Edith Wharton wrote an allegory of this very process: of the way stories acquire new meanings over time. Like most novels, “The Age of Innocence” offers a version of its author’s biography. Newland Archer, the central character, is, like Wharton herself, someone who has lived long enough to see the ideals of his youth become outdated.

A literary “classic” is a recurring character in one’s life. One reads it, years go by, one reads it again, and it becomes the sum of those readings over time. One identifies with the character closest to one in age — and then one’s age changes. Eventually, each classic tells two stories: its own, and the story of all the times one has read it. In a way, in “The Age of Innocence,” Edith Wharton wrote an allegory of this very process: of the way stories acquire new meanings over time. Like most novels, “The Age of Innocence” offers a version of its author’s biography. Newland Archer, the central character, is, like Wharton herself, someone who has lived long enough to see the ideals of his youth become outdated.

IT’S NOT QUITE CLEAR

IT’S NOT QUITE CLEAR Michael Kimmelman, architecture critic at the New York Times, calls the new design ‘smart, surgical, sprawling and slightly soulless’. I would take ‘slightly soulless’ over ‘aggressively spectacular’, and given the political controversies visited on other museums due to their problematic mega-donors (the opioid Sackler family, the anarcho-libertarian Koch brothers, the police-weapon magnate Warren Kanders, and other bad actors), such a review counts as a rave. And by and large the new MoMA is a success. Of course, there are some missteps. The walls darken in the Surrealist galleries, as though to warn us, through mood control, that here modernism plunges into the unconscious. The new MoMA is more open to campy artists like Florine Stettheimer, brutish figures like Jean Dubuffet, and erotic fantasists like Hans Bellmer, but it is still rather reserved about overtly political artists, whether of the right or the left (revolutionary Russians stand in for many others). And though the intermedial presentation of film and photography is an advance, the lived history of these media, as registered in a noisy projector or an old magazine, is mostly lost – the contemplative rituals of painting still predominate, albeit not as much as before. Apart from a magnificent array of Brancusi sculptures, which introduces the fifth floor, a forceful mix of Post-Minimalist objects, which opens the fourth floor, and the Serra installation, which lends needed gravitas to the contemporary galleries, sculpture is still treated as secondary.

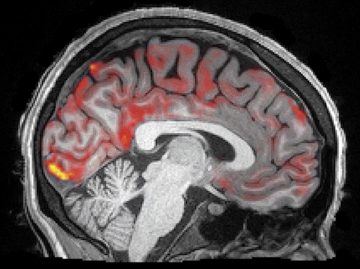

Michael Kimmelman, architecture critic at the New York Times, calls the new design ‘smart, surgical, sprawling and slightly soulless’. I would take ‘slightly soulless’ over ‘aggressively spectacular’, and given the political controversies visited on other museums due to their problematic mega-donors (the opioid Sackler family, the anarcho-libertarian Koch brothers, the police-weapon magnate Warren Kanders, and other bad actors), such a review counts as a rave. And by and large the new MoMA is a success. Of course, there are some missteps. The walls darken in the Surrealist galleries, as though to warn us, through mood control, that here modernism plunges into the unconscious. The new MoMA is more open to campy artists like Florine Stettheimer, brutish figures like Jean Dubuffet, and erotic fantasists like Hans Bellmer, but it is still rather reserved about overtly political artists, whether of the right or the left (revolutionary Russians stand in for many others). And though the intermedial presentation of film and photography is an advance, the lived history of these media, as registered in a noisy projector or an old magazine, is mostly lost – the contemplative rituals of painting still predominate, albeit not as much as before. Apart from a magnificent array of Brancusi sculptures, which introduces the fifth floor, a forceful mix of Post-Minimalist objects, which opens the fourth floor, and the Serra installation, which lends needed gravitas to the contemporary galleries, sculpture is still treated as secondary. The brain waves generated during deep sleep appear to trigger a cleaning system in the brain that protects it against Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases.

The brain waves generated during deep sleep appear to trigger a cleaning system in the brain that protects it against Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. “What would your feelings be,” asks Ambrose in Arthur Machen’s novel The House of Souls, “… if your cat or your dog began to talk to you, and to dispute with you in human accents?” He goes on:

“What would your feelings be,” asks Ambrose in Arthur Machen’s novel The House of Souls, “… if your cat or your dog began to talk to you, and to dispute with you in human accents?” He goes on: K

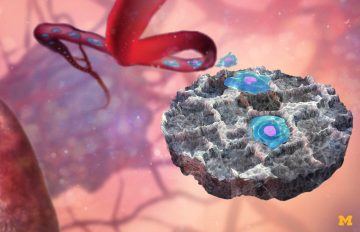

K ANN ARBOR—Invasive procedures to biopsy tissue from cancer-tainted organs could be replaced by simply taking samples from a tiny “decoy” implanted just beneath the skin, University of Michigan researchers have demonstrated in mice. These devices have a knack for attracting cancer cells traveling through the body. In fact, they can even pick up signs that cancer is preparing to spread, before cancer cells arrive. “Biopsying an organ like the lung is a risky procedure that’s done only sparingly,” said Lonnie Shea, the William and Valerie Hall Chair of biomedical engineering at U-M. “We place these scaffolds right under the skin, so they’re readily accessible.”

ANN ARBOR—Invasive procedures to biopsy tissue from cancer-tainted organs could be replaced by simply taking samples from a tiny “decoy” implanted just beneath the skin, University of Michigan researchers have demonstrated in mice. These devices have a knack for attracting cancer cells traveling through the body. In fact, they can even pick up signs that cancer is preparing to spread, before cancer cells arrive. “Biopsying an organ like the lung is a risky procedure that’s done only sparingly,” said Lonnie Shea, the William and Valerie Hall Chair of biomedical engineering at U-M. “We place these scaffolds right under the skin, so they’re readily accessible.”