Zadie Smith in the New York Review of Books:

Accounts of the muse–artist relation were anchored in the idea of male cultural production as a special category, one with particular needs—usually sexual—that the muse had been there to fulfill, perhaps even to the point of exploitation, but without whom we would have missed the opportunity to enjoy this or that beloved cultural artifact. The art wants what the art wants. Revisionary biographies of overlooked women—which began to appear with some regularity in the Eighties—were off-putting in a different way (at least to me). Unhinged in tone, by turns furious, defensive, melancholy, and tragic, their very intensity kept the muse in her place, orbiting the great man.

Accounts of the muse–artist relation were anchored in the idea of male cultural production as a special category, one with particular needs—usually sexual—that the muse had been there to fulfill, perhaps even to the point of exploitation, but without whom we would have missed the opportunity to enjoy this or that beloved cultural artifact. The art wants what the art wants. Revisionary biographies of overlooked women—which began to appear with some regularity in the Eighties—were off-putting in a different way (at least to me). Unhinged in tone, by turns furious, defensive, melancholy, and tragic, their very intensity kept the muse in her place, orbiting the great man.

Celia Paul’s memoir, Self-Portrait, is a different animal altogether. Lucian Freud, whose muse and lover she was, is rendered here—and acutely—but as Paul puts it, with typical simplicity and clarity, “Lucian…is made part of my story rather than, as is usually the case, me being portrayed as part of his.” Her story is striking. It is not, as has been assumed, the tale of a muse who later became a painter, but an account of a painter who, for ten years of her early life, found herself mistaken for a muse, by a man who did that a lot. Her book is about many things besides Freud: her mother, her childhood, her sisters, her paintings. But she neither rejects her past with Freud nor rewrites it, placing present ideas and feelings alongside diary entries and letters she wrote as a young woman, a generous, vulnerable strategy that avoids the usual triumphalism of memoir.

More here.

Azra Raza, an oncologist at Columbia, has watched too many people die from cancer. They include her patients and her husband, also a cancer specialist. She has poured her frustration into a new book, The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last.

Azra Raza, an oncologist at Columbia, has watched too many people die from cancer. They include her patients and her husband, also a cancer specialist. She has poured her frustration into a new book, The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last. Good

Good  In 1988, Valerie Solanas, the author of the 1967 female-supremacist pamphlet SCUM Manifesto, died from pneumonia at the age of fifty-two, in a single-occupancy hotel room in San Francisco. The decomposing body of the visionary writer, who famously set forth her plans “to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and destroy the male sex,” was discovered kneeling, as though in prayer, slumped over the side of the bed. The image lends itself to hagiographic depictions of Solanas—as a fallen soldier, a suffering genius, a latter-day entrant into the modernist pantheon of great artists exiled by society. Or perhaps that’s just how she appears to me. I’d rather imagine her within a tragic male tradition than an abject female one—though you’ll soon see why I’ve begun to wonder if there’s any difference.

In 1988, Valerie Solanas, the author of the 1967 female-supremacist pamphlet SCUM Manifesto, died from pneumonia at the age of fifty-two, in a single-occupancy hotel room in San Francisco. The decomposing body of the visionary writer, who famously set forth her plans “to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and destroy the male sex,” was discovered kneeling, as though in prayer, slumped over the side of the bed. The image lends itself to hagiographic depictions of Solanas—as a fallen soldier, a suffering genius, a latter-day entrant into the modernist pantheon of great artists exiled by society. Or perhaps that’s just how she appears to me. I’d rather imagine her within a tragic male tradition than an abject female one—though you’ll soon see why I’ve begun to wonder if there’s any difference. New, early data from Grail showed its liquid biopsy test not only was able to detect the presence of 12 different kinds of early-stage cancer but could also identify the disease’s location within the body before it spreads using signatures found in the bloodstream. The test also demonstrated a very low rate of false positives, at 1% or less. The former

New, early data from Grail showed its liquid biopsy test not only was able to detect the presence of 12 different kinds of early-stage cancer but could also identify the disease’s location within the body before it spreads using signatures found in the bloodstream. The test also demonstrated a very low rate of false positives, at 1% or less. The former  The rule of thumb for temperate rainforests is one third live trees, one third snags, one third nurse logs. I saw almost no dead trees in Amazonia, standing or otherwise. Things rot too fast. A dead tree can’t defend itself or maintain a symbiotic relationship with someone who will (ants). Apparently a forest can be unimaginably ancient without having a single organism make it past a few dozen years.

The rule of thumb for temperate rainforests is one third live trees, one third snags, one third nurse logs. I saw almost no dead trees in Amazonia, standing or otherwise. Things rot too fast. A dead tree can’t defend itself or maintain a symbiotic relationship with someone who will (ants). Apparently a forest can be unimaginably ancient without having a single organism make it past a few dozen years. Efforts to reduce deaths from breast cancer in women have long focused on early detection and post-surgical treatment with drugs, radiation or both to help keep the disease at bay. And both of these approaches, used alone or together, have resulted in a dramatic reduction in breast cancer mortality in recent decades. The average five-year survival rate is now 90 percent, and even higher — 99 percent — if the cancer is confined to the breast, or 85 percent if it has spread to regional lymph nodes. Yet, even though a steadily growing percentage of women now survive breast cancer, the disease still frightens many women and their loved ones. It affects one woman in eight and remains their second leading cancer killer, facts that suggest at least equal time should be given to what could be an even more effective strategy: prevention. Long-term studies involving tens of thousands of women have highlighted many protective measures that, if widely adopted, could significantly reduce women’s chances of ever getting breast cancer. Even the techniques now used to screen for possible breast cancer can help identify those women who might be singled out for special protective measures.

Efforts to reduce deaths from breast cancer in women have long focused on early detection and post-surgical treatment with drugs, radiation or both to help keep the disease at bay. And both of these approaches, used alone or together, have resulted in a dramatic reduction in breast cancer mortality in recent decades. The average five-year survival rate is now 90 percent, and even higher — 99 percent — if the cancer is confined to the breast, or 85 percent if it has spread to regional lymph nodes. Yet, even though a steadily growing percentage of women now survive breast cancer, the disease still frightens many women and their loved ones. It affects one woman in eight and remains their second leading cancer killer, facts that suggest at least equal time should be given to what could be an even more effective strategy: prevention. Long-term studies involving tens of thousands of women have highlighted many protective measures that, if widely adopted, could significantly reduce women’s chances of ever getting breast cancer. Even the techniques now used to screen for possible breast cancer can help identify those women who might be singled out for special protective measures. When walls are built through a city, strengthened with reinforced concrete and steel, separated by a strip of land where you can be shot and left to die, you don’t expect things to break through. But radio broadcasts don’t stop at borders. Political regimes can’t stop soundwaves. They just travel.

When walls are built through a city, strengthened with reinforced concrete and steel, separated by a strip of land where you can be shot and left to die, you don’t expect things to break through. But radio broadcasts don’t stop at borders. Political regimes can’t stop soundwaves. They just travel. Economics. The dismal science. All those numbers and graphs, formulas and derivations, tombstone-sized copies of Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus’s Macroeconomics (now apparently in its 19th edition), and memories of the detritus that came with them: half-filled coffee cups and overfilled ashtrays, mechanical pencils and HP-45s.

Economics. The dismal science. All those numbers and graphs, formulas and derivations, tombstone-sized copies of Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus’s Macroeconomics (now apparently in its 19th edition), and memories of the detritus that came with them: half-filled coffee cups and overfilled ashtrays, mechanical pencils and HP-45s.

The opening lines to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’ classic philosophical text, the

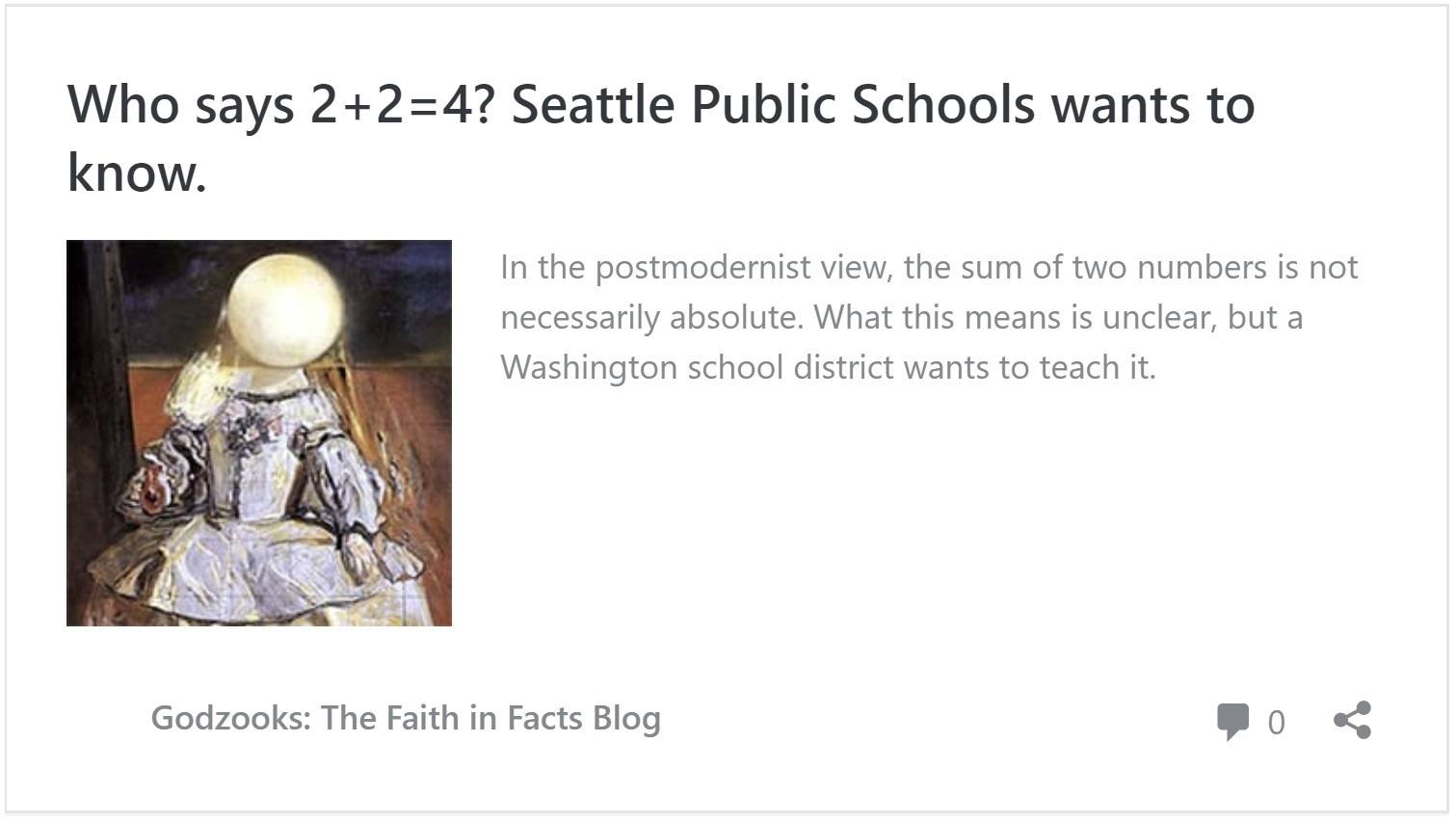

The opening lines to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes’ classic philosophical text, the  The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”

The blog post screams: “If you think 2 + 2 always equals 4, you’re a racist oppressor.”