by Derek Neal

At some point in the last couple of months, my reading about ChatGPT reached critical mass. Or, I thought it had. Try as I might, I couldn’t escape the little guy; everywhere I turned there was talk of ChatGPT—what it meant for the student essay, how it could be used in business, how the darn thing actually worked, whether it was really smart, or actually, really stupid. At work, where I teach English language to international university students, I quickly found myself grading ChatGPT written essays (perfect grammar but overly vague and general) and heard predictions that soon our job would be to teach students how to use AI, as opposed to teaching them how to write. It was all so, so depressing. This led to my column a few months ago wherein I launched a defense of writing and underlined its role in the shaping of humans’ ability to think abstractly, as it seemed to me that outsourcing our ability to write could conceivably lead us to return to a pre-literate state, one in which our consciousness is shaped by oral modes of thought. This is normally characterized as a state of being that values direct experience, or “close proximity to the human life world,” while shunning abstract categories and logical reasoning, which are understood to be the result of literate cultures. It is not just writing that is at stake, but an entire worldview shaped by literacy.

The intervening months have only strengthened my convictions. It seems even clearer to me now that the ability to write will become a niche subject, similar to that of Latin, which will be pursued by fewer and fewer students until it disappears from the curriculum altogether. The comparison to Latin is intentional, as Latin was once the language used for all abstract reasoning (Walter Ong, in Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word, even goes so far as to say that the field of modern science may not have arisen without the use of Learned Latin, which was written but never spoken). In the same way, a written essay will come to be seen as a former standard of argumentation and extended analysis. Read more »

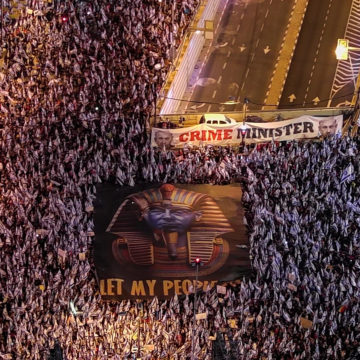

The state of Israel is on the brink of deliquescence. A corrupt multi-indicted prime minister has handed the reins of government to extremist (read: blood-thirsty) right-wing (read: populist imperialist) religious (read: obscurantist) coalition parties whose alliance is based on a net refusal to heed the Israeli Supreme Court and a pact to instil a theocratic regime where there has been, since the state’s creation in 1948, a democracy. Both these goals are to be achieved by changing the law, giving parliament (the Israeli knesset) the right to dictate the terms of justice to the courts of justice. It is a situation the philosopher Plato had staged at the start of his Republic, back in the 4th century BC.

The state of Israel is on the brink of deliquescence. A corrupt multi-indicted prime minister has handed the reins of government to extremist (read: blood-thirsty) right-wing (read: populist imperialist) religious (read: obscurantist) coalition parties whose alliance is based on a net refusal to heed the Israeli Supreme Court and a pact to instil a theocratic regime where there has been, since the state’s creation in 1948, a democracy. Both these goals are to be achieved by changing the law, giving parliament (the Israeli knesset) the right to dictate the terms of justice to the courts of justice. It is a situation the philosopher Plato had staged at the start of his Republic, back in the 4th century BC.

School Boards across the country have become radicalized, energized, weaponized. They have become the new political battleground where extremist right-wing ideologues test the political waters. The plan is to infiltrate the schools, use them as the megaphone to broadcast the GOP’s agenda, with lots of soapboxing and grandstanding thrown in.

School Boards across the country have become radicalized, energized, weaponized. They have become the new political battleground where extremist right-wing ideologues test the political waters. The plan is to infiltrate the schools, use them as the megaphone to broadcast the GOP’s agenda, with lots of soapboxing and grandstanding thrown in.

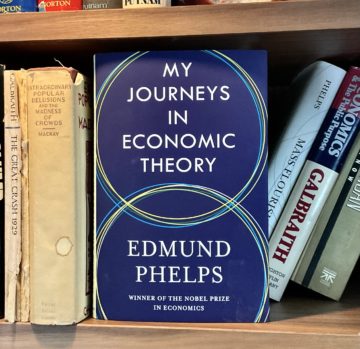

On page 184 of Edmund Phelps’ new book, My Journeys In Economic Theory, he tells the story of a lunch party with friends, at which, presumably after the plates were cleared (but not the glasses), the then 80-something-year-old 2006 Nobel Prize winner in Economics belted out “Garden Grow.”

On page 184 of Edmund Phelps’ new book, My Journeys In Economic Theory, he tells the story of a lunch party with friends, at which, presumably after the plates were cleared (but not the glasses), the then 80-something-year-old 2006 Nobel Prize winner in Economics belted out “Garden Grow.” Last month I saw the Whitney exhibit “no existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria.” As you might remember, Maria was a Category 4 storm that hit Puerto Rico September 20, 2017. According to Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 4,645 Puerto Ricans died as a result of the storm, but according to the Puerto Rican government, only 64 died. The Whitney’s museum label stated that the smaller number “not only insulted the populace with its miscalculation but also undercounted at-risk sectors that experienced increased deaths from accidents, cardiac conditions, diabetes, suicide, and even leptospirosis—a usually rare, potentially deadly, yet preventable bacterial infection spread by rats that grew prevalent in the months following the storm due to contaminated water.” A year after the hurricane, an impromptu installation of over 3,000 pairs of shoes was placed in front of Puerto Rican government buildings to memorialize the actual number of dead..

Last month I saw the Whitney exhibit “no existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria.” As you might remember, Maria was a Category 4 storm that hit Puerto Rico September 20, 2017. According to Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 4,645 Puerto Ricans died as a result of the storm, but according to the Puerto Rican government, only 64 died. The Whitney’s museum label stated that the smaller number “not only insulted the populace with its miscalculation but also undercounted at-risk sectors that experienced increased deaths from accidents, cardiac conditions, diabetes, suicide, and even leptospirosis—a usually rare, potentially deadly, yet preventable bacterial infection spread by rats that grew prevalent in the months following the storm due to contaminated water.” A year after the hurricane, an impromptu installation of over 3,000 pairs of shoes was placed in front of Puerto Rican government buildings to memorialize the actual number of dead.. At the core of Susan Neiman’s new book Left is not Woke, which is an attempt to sever what she sees as reactionary intellectual tendencies from admirable progressive goals, is the idea that for progressive values to be sustainable, their roots in the philosophy of the European Enlightenment need to be recognized and nourished. “If we continue to misconstrue the Enlightenment”, she says, “we can hardly appeal to its resources.”

At the core of Susan Neiman’s new book Left is not Woke, which is an attempt to sever what she sees as reactionary intellectual tendencies from admirable progressive goals, is the idea that for progressive values to be sustainable, their roots in the philosophy of the European Enlightenment need to be recognized and nourished. “If we continue to misconstrue the Enlightenment”, she says, “we can hardly appeal to its resources.” I first heard “The Blundering Generation” in the 1990s when I was taking a course on Civil War history. As my professor explained, the early 20th century saw a new cohort of historians who no longer personally remembered the war and debated anew the nature of its origins. They were trying to move past the earlier, caustic interpretations of Northerners and Southerners who openly blamed each other, the former decrying the Southern “slaveocracy” and the latter bemoaning the “war of Northern aggression.” So instead, these thinkers at the vanguard of historical study decided to blame everyone. Or no one.

I first heard “The Blundering Generation” in the 1990s when I was taking a course on Civil War history. As my professor explained, the early 20th century saw a new cohort of historians who no longer personally remembered the war and debated anew the nature of its origins. They were trying to move past the earlier, caustic interpretations of Northerners and Southerners who openly blamed each other, the former decrying the Southern “slaveocracy” and the latter bemoaning the “war of Northern aggression.” So instead, these thinkers at the vanguard of historical study decided to blame everyone. Or no one. Sughra Raza. Santiago Street Color, Chile, November 2017.

Sughra Raza. Santiago Street Color, Chile, November 2017. Spanning just shy of a thousand years, al-Andalus or Muslim Spain (711-1492), has a riveting history. To picture the Andalus is to imagine a world that gratifies at once the intellect, the spirit and all the senses; it has drawn critical scholars, poets and musicians alike. Barring cycles of turbulence, it is remembered as an intellectual utopia, a time of unsurpassed plentitude and civilizational advancements, and most significantly, as “la Convivencia” or peaceful coexistence of the three Abrahamic faiths brought together as a milieu. Al-Andalus was a syncretic culture shaped by influences from three continents— Africa, Asia and Europe – under Muslim rule. This civilization came to be known as a golden age for setting standards across all human endeavors, a bridge between Eastern and Western learning, sciences and the fine arts, between the public and private, native and foreign, sacred and secular— a phenomenon hitherto unknown in antiquity. The decline and eventual collapse of al-Andalus is no less of a legend; it is a history of in-fighting and brutal intolerance perpetrated throughout the three centuries of the Spanish Inquisition (1478-1834) with ramifications to witness in our own times. The stark contrast between the Convivencia and the Inquisition makes al-Andalus a poignant story of reversals.

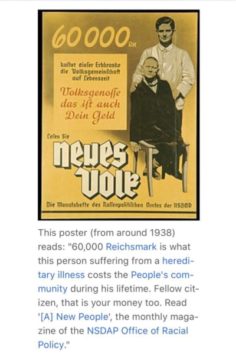

Spanning just shy of a thousand years, al-Andalus or Muslim Spain (711-1492), has a riveting history. To picture the Andalus is to imagine a world that gratifies at once the intellect, the spirit and all the senses; it has drawn critical scholars, poets and musicians alike. Barring cycles of turbulence, it is remembered as an intellectual utopia, a time of unsurpassed plentitude and civilizational advancements, and most significantly, as “la Convivencia” or peaceful coexistence of the three Abrahamic faiths brought together as a milieu. Al-Andalus was a syncretic culture shaped by influences from three continents— Africa, Asia and Europe – under Muslim rule. This civilization came to be known as a golden age for setting standards across all human endeavors, a bridge between Eastern and Western learning, sciences and the fine arts, between the public and private, native and foreign, sacred and secular— a phenomenon hitherto unknown in antiquity. The decline and eventual collapse of al-Andalus is no less of a legend; it is a history of in-fighting and brutal intolerance perpetrated throughout the three centuries of the Spanish Inquisition (1478-1834) with ramifications to witness in our own times. The stark contrast between the Convivencia and the Inquisition makes al-Andalus a poignant story of reversals. Some people are arguing that the removal of mask mandates in hospitals is a form of eugenics. Tamara Taggart, President of Down Syndrome BC, said on “

Some people are arguing that the removal of mask mandates in hospitals is a form of eugenics. Tamara Taggart, President of Down Syndrome BC, said on “

Who doesn’t love a three-day weekend? If an extra day to relax isn’t good enough, the following week always seems to go quickly, making a Memorial Day, Labor Day, or a bank holiday in the UK, the gift that keeps on giving. Of course, most of us should consider ourselves lucky only to have to work a 5-day week. No law of the universe says a work week has to be 5 days. In fact, the concept of a 40-hour workweek is relatively new; it was only on June 25, 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which limited the workweek to 44 hours, and two years later, Congress amended that to 40 hours.

Who doesn’t love a three-day weekend? If an extra day to relax isn’t good enough, the following week always seems to go quickly, making a Memorial Day, Labor Day, or a bank holiday in the UK, the gift that keeps on giving. Of course, most of us should consider ourselves lucky only to have to work a 5-day week. No law of the universe says a work week has to be 5 days. In fact, the concept of a 40-hour workweek is relatively new; it was only on June 25, 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which limited the workweek to 44 hours, and two years later, Congress amended that to 40 hours.

In the 1960s, when I was a boy growing up on the west side of Montreal, whenever my father needed a hit of soul food — a smoked-meat sandwich, some pickled herring, or a ball of chopped liver with grivenes—he would head east (northeast, really, in my hometown’s skewed-grid street plan) to his old neighborhood on the Plateau. He would make for Schwartz’s, or Waldman’s, to the shops lining boulevard St.-Laurent, once known as “the Main” in memory of its service as a major artery through the Jewish part of town before the district changed hands: or rather, reverted to majority rule. On weekends my father would travel a little farther, in the direction of Mile End, to either of two places, St. Viateur Bagels and Fairmount Bagels, each located on the street from which it took its name and each, as its name candidly proposed, a baker and purveyor of bagels.

In the 1960s, when I was a boy growing up on the west side of Montreal, whenever my father needed a hit of soul food — a smoked-meat sandwich, some pickled herring, or a ball of chopped liver with grivenes—he would head east (northeast, really, in my hometown’s skewed-grid street plan) to his old neighborhood on the Plateau. He would make for Schwartz’s, or Waldman’s, to the shops lining boulevard St.-Laurent, once known as “the Main” in memory of its service as a major artery through the Jewish part of town before the district changed hands: or rather, reverted to majority rule. On weekends my father would travel a little farther, in the direction of Mile End, to either of two places, St. Viateur Bagels and Fairmount Bagels, each located on the street from which it took its name and each, as its name candidly proposed, a baker and purveyor of bagels.