by Eric Bies

In geometry, a line goes on and on: it goes on and on and never stops. In poetry, a line goes on as long as the poet lets it….though in practice this rarely means more than six or seven words at a stretch.

In geometry, a line goes on and on: it goes on and on and never stops. In poetry, a line goes on as long as the poet lets it….though in practice this rarely means more than six or seven words at a stretch.

I open the novel lying next to me—an attractively typeset hardback Bolaño—and its lines smile with the teeth of all of twelve or fourteen. Words: like the Greeks at Thermopylae, they have, somehow, to say more, do more, be more when they amass in minor number. That’s the poet’s problem.

Of course, the poet is more than welcome to set about the rather dry, administrative task of composing and arranging a rank and file of discrete poetic lines: in the end times we shall all stand watching from the horse-shaped shade of an outsize bicorn as the lines march out onto the page, ready to clash with or be routed by the reader’s eye. And this makes for a nice image, but it does nothing to dispel the poet’s problem: that blasted matter of saying more with less. If only the poet had paid a little closer attention in class. For even I can hear it now. It’s the sound of a single line begging to be many.

Such a line, whose contents spill over into another (and perhaps another, and not infrequently another yet), zigging and zagging in clots and clauses of continuous thought, participates in a process called enjambment. Most halfway okay poems—those desirous both of basic interpretability and, well, the appearance of poetry—do usually enjoy enjambments, of which the poet ensures an artfulness sufficient to staving off suspicions as to their simply having fed a sentence to a sushi chef. But then there really are those poems that one could say are little more than their dismemberments. What we end up with, for instance, when we lift the line breaks from a famous poem by a New Jersey physician is a sentence merely, and an unremarkable one at that.

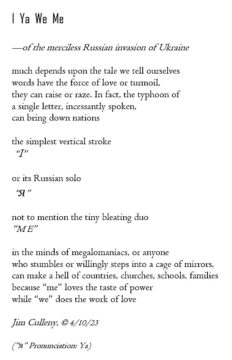

See, so much depends upon a line break. William Carlos Williams demonstrated as much when he punched this one out on his typewriter:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens

The poem, which is everything modernists like Williams taught us a poem could be—studiously irregular, liberally aerated, colloquially disembodied—is clearly only barely a poem. (Actually, it’s safe to say it shares more in structure and spirit with the readymades of Marcel Duchamp, asserting new perspectives on everyday objects, than anything Longfellow left us.)

But what does depend upon a red wheelbarrow, glazed with rainwater, beside the white chickens? Read more »

There has been talk in recent years of what is termed “the internet novel.” The internet, or more precisely, the smartphone, poses a problem for novels. If a contemporary novel wants to seem realistic, or true to life, it must incorporate the internet in some way, because most people spend their days immersed in it. Characters, for example, must check their phones frequently. For example:

There has been talk in recent years of what is termed “the internet novel.” The internet, or more precisely, the smartphone, poses a problem for novels. If a contemporary novel wants to seem realistic, or true to life, it must incorporate the internet in some way, because most people spend their days immersed in it. Characters, for example, must check their phones frequently. For example:

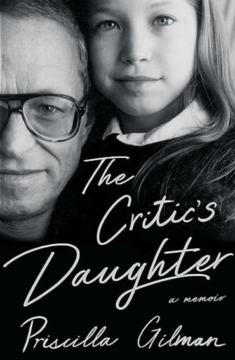

Richard Gilman (1923-2006)—a revered and feared American critic of theater, film and fiction in the mid-century patrician grain of Eric Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann and Robert Brustein—was a self-absorbed titan of insecurity and the best writing teacher I ever had. Negotiating the minefield of this man’s mercurial moodiness, beginning at age 22, was one of the main galvanizing experiences of my pre-professional life.

Richard Gilman (1923-2006)—a revered and feared American critic of theater, film and fiction in the mid-century patrician grain of Eric Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann and Robert Brustein—was a self-absorbed titan of insecurity and the best writing teacher I ever had. Negotiating the minefield of this man’s mercurial moodiness, beginning at age 22, was one of the main galvanizing experiences of my pre-professional life.