by Tim Sommers

Suppose a small group of people are stranded together on a desert island. They have no fresh water or food – until they come across a stash of coconuts. They can drink the milk and eat the coconut meat to survive. But how do they divide up the coconuts fairly between them?

The coconuts are not the product of anyone’s hard work or ingenuity. They are manna-from-heaven. In such circumstances, in a sense, no one deserves anything. So, the question is how to distribute something valuable, even essential, but which no one has any prior claim upon, in an ethical way. In other words, what is the appropriate principle of distributive fairness in such a case?

The most obvious suggestion is that the coconuts should be distributed equally. And that may well be the right answer. Many people consider equality the presumptive fair distribution, especially in manna-from-heaven situations like this. Distributions that depart from strict equality, many believe, must be justified, but equality requires no justification. For example, suppose we also find buried treasure on the island. Various arguments could be made that one person made a decisive contribution to the discovery that others didn’t, but isn’t the starting place an equal distribution?

But suppose after most of the coconuts are distributed equally there is one coconut left. For the sake of argument, imagine single coconuts are not divisible or fungible for some reason and so one coconut cannot be shared. What do we do with the extra coconut?

Strict equality seems to imply that you should just throw it away to avoid making the distribution unequal. This is called the leveling-down problem. You can almost always increase the amount of equality in an unequal distribution by taking stuff from the better-off and simply throwing it away. If equality is valuable in and of itself, then any situation can be made fairer (at least in one way) by leveling down how much the better-off have so that there is less inequality – even if this makes no one better-off in absolute terms.

Maybe, for this reason, we shouldn’t care about equality in and of itself, after all. Why do we? Read more »

.

.

Some things in life are very hard to give up. For me, I hope in a most singular manner, it is bullshit. I have spent nearly twenty years reading whatever literature I can find on what bullshit might be. Since the publication of Professor Harry Frankfurt’s

Some things in life are very hard to give up. For me, I hope in a most singular manner, it is bullshit. I have spent nearly twenty years reading whatever literature I can find on what bullshit might be. Since the publication of Professor Harry Frankfurt’s  In the late 1960’s and early 70’s, my maternal grandmother spent a lot of time in the United States. She would return to Iran, her suitcase filled with presents like candy and fruity bubble gum for her grandchildren, and pretty shirts and dresses for our mom. She also brought back a part of her daily American life: cartons of red Winston cigarettes, Crest toothpaste, hand and face creams with English writings on the bottles, and Dial Soap in that beautiful saffron gold color that was unlike any soap I had seen or smelled before. Our soaps in Iran were usually either flower scented and over perfumed, or green and organic because of the local olive oil used to make them. Everyone valued the green soaps, but I just wanted the American gold soap. I would watch her put the soap back in a plastic container after her shower to keep it from drying and when she was away from her room, I would go open the plastic container and smell the

In the late 1960’s and early 70’s, my maternal grandmother spent a lot of time in the United States. She would return to Iran, her suitcase filled with presents like candy and fruity bubble gum for her grandchildren, and pretty shirts and dresses for our mom. She also brought back a part of her daily American life: cartons of red Winston cigarettes, Crest toothpaste, hand and face creams with English writings on the bottles, and Dial Soap in that beautiful saffron gold color that was unlike any soap I had seen or smelled before. Our soaps in Iran were usually either flower scented and over perfumed, or green and organic because of the local olive oil used to make them. Everyone valued the green soaps, but I just wanted the American gold soap. I would watch her put the soap back in a plastic container after her shower to keep it from drying and when she was away from her room, I would go open the plastic container and smell the

With apologies to Charles Dickens, it will be the best of times, it will be the worst of times.

With apologies to Charles Dickens, it will be the best of times, it will be the worst of times.

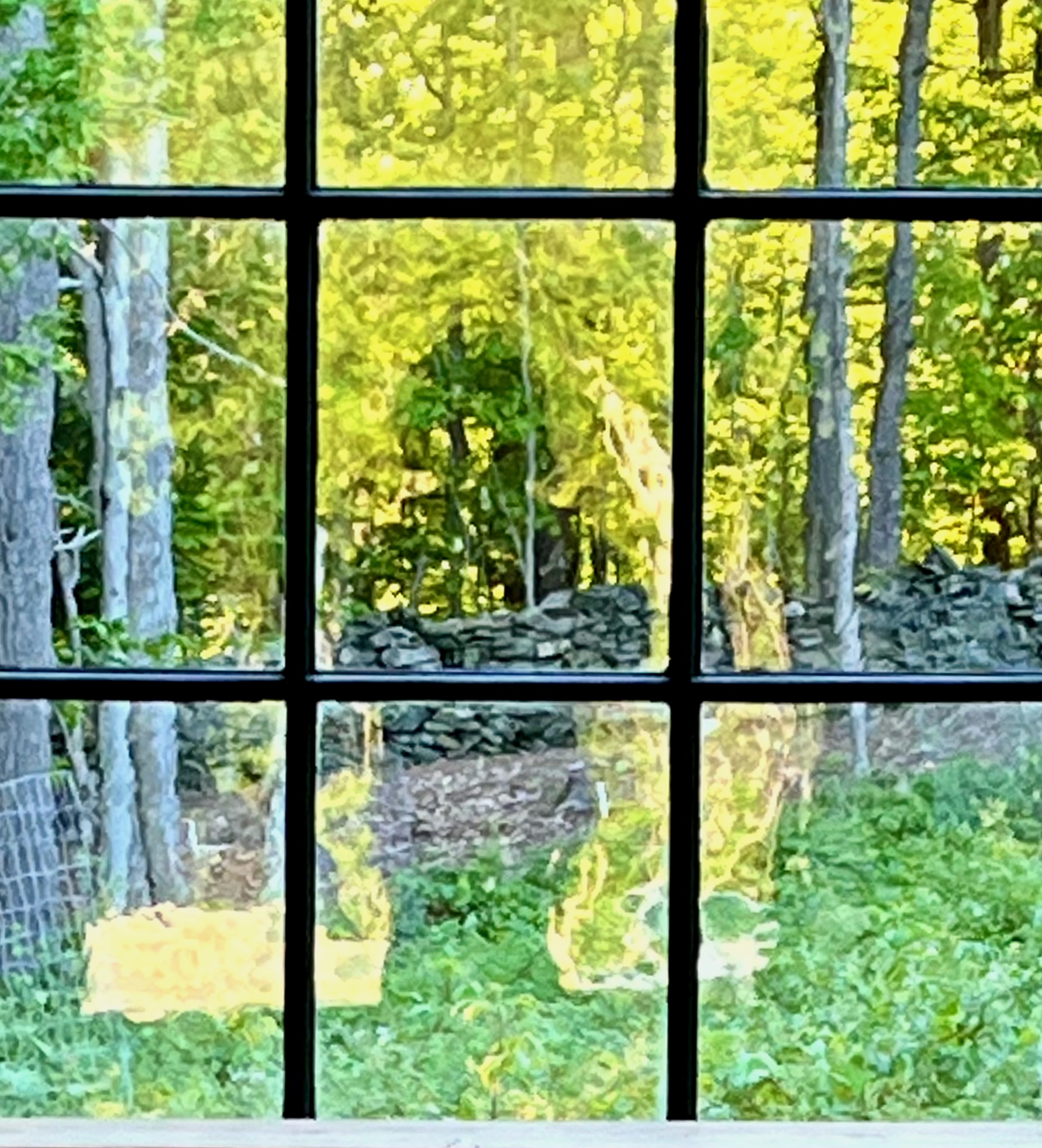

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Early Summer, May 2024.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in Early Summer, May 2024.