by Carol A Westbrook

My father gave me an electric drill and power saw as a wedding gift. The year was 1974, and the other guests at my wedding shower were puzzled, having gifted to me the usual assortment of mixing bowls, Corning ware, linens, and fondue pot. I appreciated all the gifts, but I was delighted with the hand tools, knowing I would get as much use out of them as I would from the hand mixer.

Dad knew I could handle the tools, since he himself had taught me to use them, as he had taught me many other things that were traditionally considered a boys’ domain the 1960’s. He taught me some basic electronics, and together we used copper wire to connect a bell, a battery, and a switch that rang the bell. We made a crystal radio and listened to the world. Dad even taught me how to use a soldering iron. This was ironic because my mother could have taught me, given her experience soldering radios at the Admiral Company during World Was II. But Mom was out of practice, since she no longer worked at Admiral–she quit when the war ended so her job could go to a returning veteran, and because this was men’s work. She felt that her place was in the home.

With these simple projects my Dad taught me to navigate the physical world with as much understanding and confidence as any boy my age.

Another tool my father gave me was a camera, and lessons in how to use it. He showed me how to frame a good shot; how to photograph people and landscapes. He taught me the needed technical skills, too: how to use his light meter, how to set the f-stop, how to choose and load the correct film, and how to develop and print film in our home darkroom. I was a passable photographer in those days before iPhones and digital photography. Read more »

As a child, I feared dogs. A neighbor kept his German Shepherds, Heidi and Sarge, in a large pen along the alley. The yard and house, his parents’, were the biggest for many blocks. On the alley side, the chain link fence stood 10 feet. The dogs would charge out of their houses silently and hurl their bodies at the fence snarling and barking. I was caught unaware at the fence a few times. My stomach curdled and legs buckled. My mother’s family are dog people. My grandparents cared for a series of large overfed dogs who cavorted in the swamps surrounding their Massachusetts home and otherwise slumped under the kitchen table waiting for my grandmother to put together meals of breakfast scraps bound with maple syrup or for treats from a cookie jar on her counter. My uncles had shambling dogs who would leap into rough water off Cape Cod to retrieve balls from seaweed choked waves. As their fur dried, they smelled of sour salt water and general funk. At the rented house, they showed a gentle deference to humans and lolled on the grass or carpet while my cousins and I ate and talked.

As a child, I feared dogs. A neighbor kept his German Shepherds, Heidi and Sarge, in a large pen along the alley. The yard and house, his parents’, were the biggest for many blocks. On the alley side, the chain link fence stood 10 feet. The dogs would charge out of their houses silently and hurl their bodies at the fence snarling and barking. I was caught unaware at the fence a few times. My stomach curdled and legs buckled. My mother’s family are dog people. My grandparents cared for a series of large overfed dogs who cavorted in the swamps surrounding their Massachusetts home and otherwise slumped under the kitchen table waiting for my grandmother to put together meals of breakfast scraps bound with maple syrup or for treats from a cookie jar on her counter. My uncles had shambling dogs who would leap into rough water off Cape Cod to retrieve balls from seaweed choked waves. As their fur dried, they smelled of sour salt water and general funk. At the rented house, they showed a gentle deference to humans and lolled on the grass or carpet while my cousins and I ate and talked. Having taught Philosophy for 46 years in three Universities—two State and one private—and never taught a Critical Thinking course one might have some questions about my choice of topic. My response is two-fold. First, there is a sense in which no matter what the topic of a particular course philosophy is always about critical thinking. One’s lectures are intended to model careful, reflective thought, sensitive to both the considerations favoring one’s views as well as the strongest objections. Second, because it is always going to be essential to use and define essential logical terminology.

Having taught Philosophy for 46 years in three Universities—two State and one private—and never taught a Critical Thinking course one might have some questions about my choice of topic. My response is two-fold. First, there is a sense in which no matter what the topic of a particular course philosophy is always about critical thinking. One’s lectures are intended to model careful, reflective thought, sensitive to both the considerations favoring one’s views as well as the strongest objections. Second, because it is always going to be essential to use and define essential logical terminology.

For a Baptist, the Bible exists like gravity. Not believing in gravity will not change the outcome if you step off a building; not believing the Bible will not change the consequences if you ignore its precepts and commands. Both are laws of nature, fixed and unchanging.

For a Baptist, the Bible exists like gravity. Not believing in gravity will not change the outcome if you step off a building; not believing the Bible will not change the consequences if you ignore its precepts and commands. Both are laws of nature, fixed and unchanging.

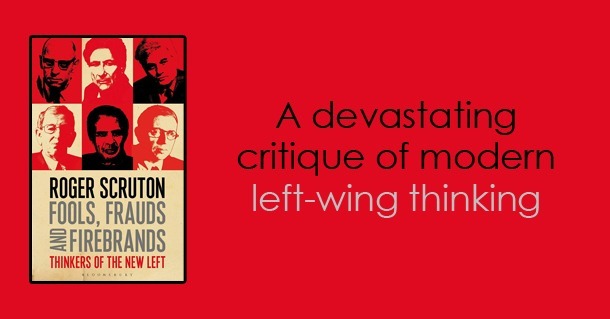

Few topics have captured the attention of the internet literati more than the topic of Jordan B. Peterson. Peterson,

Few topics have captured the attention of the internet literati more than the topic of Jordan B. Peterson. Peterson,

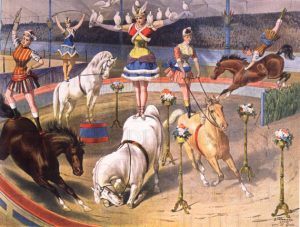

What follows is part of a collaborative project between a historian and a student of medicine called “The Temperature of Our Time.” In forming diagnoses, historians and doctors gather what Carlo Ginzburg has called “small insights”—clues drawn from “concrete experience”—to expose the invisible: a forensic assessment of condition, the origins of an idiopathic illness, the trajectory of an idea through time. Taking the temperature of our time means reading vital signs and symptoms around a fixed theme or metaphor—in this case, the circus.

What follows is part of a collaborative project between a historian and a student of medicine called “The Temperature of Our Time.” In forming diagnoses, historians and doctors gather what Carlo Ginzburg has called “small insights”—clues drawn from “concrete experience”—to expose the invisible: a forensic assessment of condition, the origins of an idiopathic illness, the trajectory of an idea through time. Taking the temperature of our time means reading vital signs and symptoms around a fixed theme or metaphor—in this case, the circus. Beauty has long been understood as the highest form of aesthetic praise sharing space with goodness, truth, and justice as a source of ultimate value. But in recent decades, despite calls for its revival, beauty has been treated as the ugly stepchild banished by an art world seeking forms of expression that capture the seedier side of human existence. It is a sad state of affairs when the highest form of aesthetic praise is dragged through the mud. Might the problem be that beauty from the beginning has been misunderstood?

Beauty has long been understood as the highest form of aesthetic praise sharing space with goodness, truth, and justice as a source of ultimate value. But in recent decades, despite calls for its revival, beauty has been treated as the ugly stepchild banished by an art world seeking forms of expression that capture the seedier side of human existence. It is a sad state of affairs when the highest form of aesthetic praise is dragged through the mud. Might the problem be that beauty from the beginning has been misunderstood? There is a famous exchange in Casablanca between Rick (Humphrey Bogart) and Captain Renault (Claude Rains):

There is a famous exchange in Casablanca between Rick (Humphrey Bogart) and Captain Renault (Claude Rains):