by Michael Liss

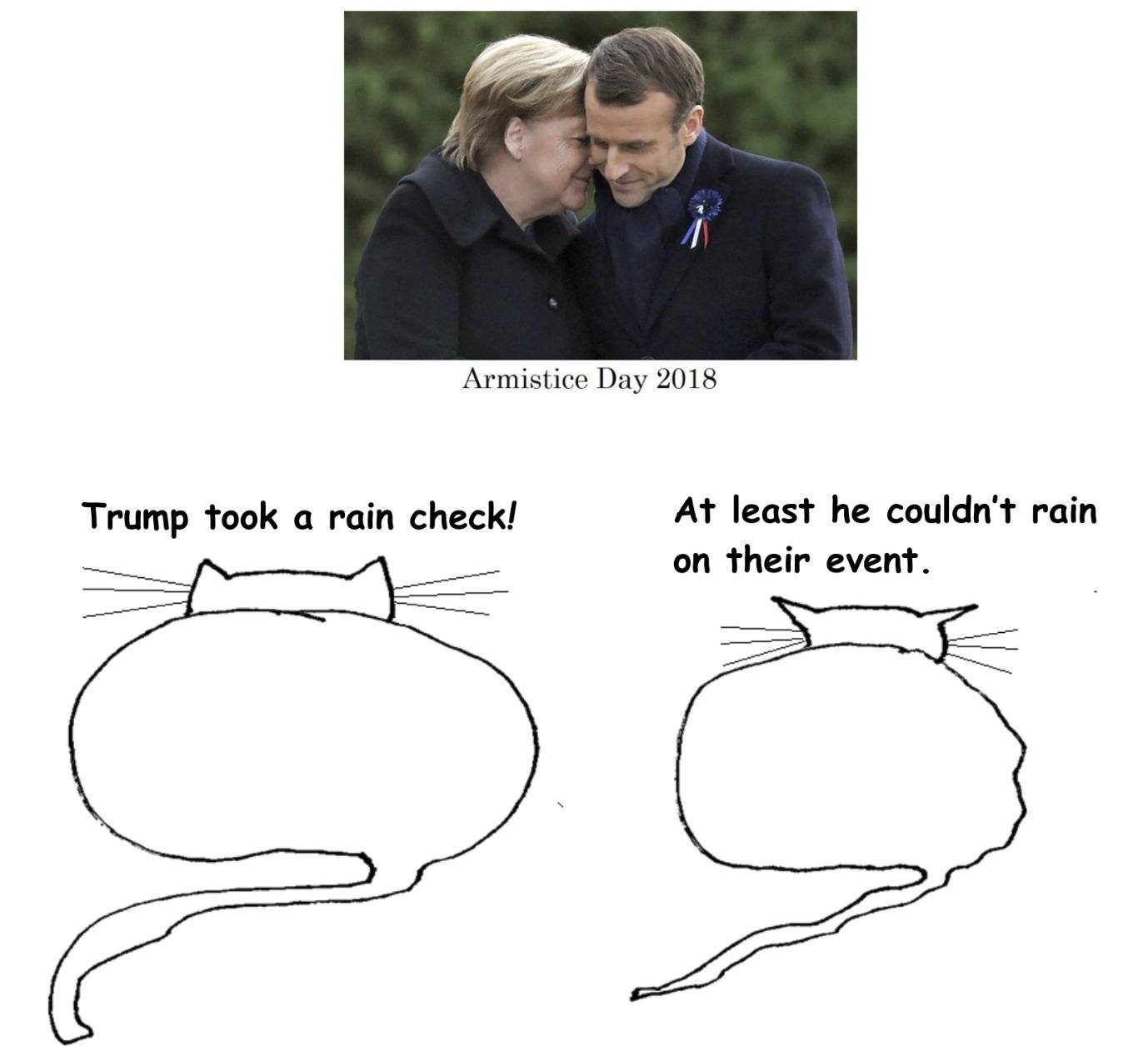

This past Sunday, November 11, marked the Centennial of Armistice Day, the European commemoration of the agreement to end World War I. Representatives from more than 60 countries attended carefully choreographed ceremonies to honor the sacrifice of those who fought.

This past Sunday, November 11, marked the Centennial of Armistice Day, the European commemoration of the agreement to end World War I. Representatives from more than 60 countries attended carefully choreographed ceremonies to honor the sacrifice of those who fought.

The Europeans take the Great War seriously. Americans really don’t. It just doesn’t feel like our war. To us, it’s an old chest filled with musty, tattered maps and the remains of broken monarchies and shattered ambitions. Even the early film footage, jerky and grainy in black and white, looks more like a silent movie than something real. We know we participated, and naturally we were heroic. Our boys saved the Allied powers from the Huns, all the while singing “Over There” and wooing the local pulchritude. It’s what we broad-shouldered, brave, optimistic, can-do Americans do.

But, if you want to contextualize our actual contribution, consider the following:

The United States committed 2.8 million servicemen to the war, and suffered 53,402 killed in action, 63,114 deaths from disease and other causes, and about 205,000 wounded. On an absolute level, that’s a lot of lives. But, by contrast, in just one extended, insane battle, the Europeans fought the Somme Offensive, with more than 3 million men engaged and 1 million casualties. Then there was Gallipoli, the infamous, disastrous push by then-First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill in the Dardanelles, which provided the Ottoman Empire with its last meaningful military victory, and included a horrific sacrifice by ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand combined forces) and half a million casualties. And Verdun (between the French and the Germans), which lasted close to 11 months in 1916, and yielded nearly 700,000 casualties and more than 300,000 dead. And Passchendaele (3rd Battle of Ypres, Flanders Fields), between Great Britain, France, Belgium and Germany, in July to November 1917, in which the dead and wounded may have been as high as 700,000. And Operation Michael, the last major German offensive in the West (Germany, the UK, France, and, finally, the United States), which had almost 500,000 casualties. That, of course, skips every battle between the Germans and the Russians. Read more »

In a recent study, data scientists based in Japan found that classical music over the past several centuries has followed laws of evolution. How can non-living cultural expression adhere to these rules?

In a recent study, data scientists based in Japan found that classical music over the past several centuries has followed laws of evolution. How can non-living cultural expression adhere to these rules?

The crocodiles know. They form pincers on either side of the crossing point. Richard says they feel the vibration of all those hooves along the riverbank above them.

The crocodiles know. They form pincers on either side of the crossing point. Richard says they feel the vibration of all those hooves along the riverbank above them.

By chance, I chose as holiday reading (awaiting my attention since student days) The Epic of Gilgamesh, a Penguin Classics bestseller, part of the great library of Ashur-bani-pal that was buried in the wreckage of Nineveh when that city was sacked by the Babylonians and their allies in 612 BCE. Gilgamesh is a surprisingly modern hero. As King, he accomplishes mighty deeds, including gaining access to the timber required for his building plans by overcoming the guardian of the forest. But this victory comes at a cost; his beloved friend Enkidu opens by hand the gate to the forest when he should have smashed his way in with his axe. This seemingly minor lapse, like Moses’ minor lapse in striking the rock when he should have spoken to it, proves fatal. Enkidu dies, and Gilgamesh, unable to accept this fact, sets out in search of the secret of immortality, only to learn that there is no such thing. He does bring back from his journey a youth-restoring herb, but at the last moment even this is stolen from him by a snake when he turns aside to bathe. In due course, he dies, mourned by his subjects and surrounded by a grieving family, but despite his many successes, what remains with us is his deep disappointment. He has not managed to accomplish what he set out to do.

By chance, I chose as holiday reading (awaiting my attention since student days) The Epic of Gilgamesh, a Penguin Classics bestseller, part of the great library of Ashur-bani-pal that was buried in the wreckage of Nineveh when that city was sacked by the Babylonians and their allies in 612 BCE. Gilgamesh is a surprisingly modern hero. As King, he accomplishes mighty deeds, including gaining access to the timber required for his building plans by overcoming the guardian of the forest. But this victory comes at a cost; his beloved friend Enkidu opens by hand the gate to the forest when he should have smashed his way in with his axe. This seemingly minor lapse, like Moses’ minor lapse in striking the rock when he should have spoken to it, proves fatal. Enkidu dies, and Gilgamesh, unable to accept this fact, sets out in search of the secret of immortality, only to learn that there is no such thing. He does bring back from his journey a youth-restoring herb, but at the last moment even this is stolen from him by a snake when he turns aside to bathe. In due course, he dies, mourned by his subjects and surrounded by a grieving family, but despite his many successes, what remains with us is his deep disappointment. He has not managed to accomplish what he set out to do. On his journey, Gilgamesh meets the one man who has achieved immortality, Utnapishtim, survivor of a flood remarkably similar, even in its details, to the Flood in the Bible. Reading of this sent me back to Genesis, and hence to two other books,

On his journey, Gilgamesh meets the one man who has achieved immortality, Utnapishtim, survivor of a flood remarkably similar, even in its details, to the Flood in the Bible. Reading of this sent me back to Genesis, and hence to two other books, Comparing Hebrew with Cuneiform may seem like a suitable gentlemanly occupation for students of ancient literature, but of no practical importance. On the contrary, I maintain that what emerges is of major contemporary relevance.

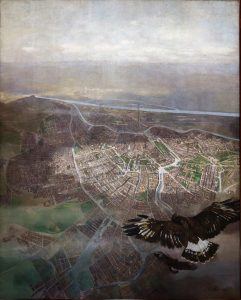

Comparing Hebrew with Cuneiform may seem like a suitable gentlemanly occupation for students of ancient literature, but of no practical importance. On the contrary, I maintain that what emerges is of major contemporary relevance. When architect Otto Wagner commissioned this large painting by Carl Moll for the Kaiser’s personal railroad station in Vienna in 1899, he might not have seen the irony of an eagle’s view of the city. View of Vienna from a Balloon envisions a future beyond rails in which a bird shows the way to a whole new way of looking at landscape, one that would renew the way we view nature itself, hardly more than a 100 years later. If that painting were done today, the eagle would be replaced by a small four-cornered device with a camera and four rotary blades to keep it aloft: the drone.

When architect Otto Wagner commissioned this large painting by Carl Moll for the Kaiser’s personal railroad station in Vienna in 1899, he might not have seen the irony of an eagle’s view of the city. View of Vienna from a Balloon envisions a future beyond rails in which a bird shows the way to a whole new way of looking at landscape, one that would renew the way we view nature itself, hardly more than a 100 years later. If that painting were done today, the eagle would be replaced by a small four-cornered device with a camera and four rotary blades to keep it aloft: the drone.

This year – 2018 – marks something truly auspicious. This is the semi-centennial of the invention of the Zombie. In these fifty years, let’s face it, we have been completely overrun. Zombies are everywhere. They are in our movies, tv shows, books, and comic books, plus, out here in the real world where the Center for Disease Control has a comprehensive Zombie preparedness and education plan and there are Zombie-walks, Zombie-conventions, and, anyway, didn’t you see them this Halloween? The most popular Zombie tv show, “The Walking Dead”, has been streaming for almost ten years – and the comic book it is based on is still going strong. At least one Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winning author has written a straight-up zombie novel – Colson Whitehead’s “Zone One”. So, what’s with all the Zombies?

This year – 2018 – marks something truly auspicious. This is the semi-centennial of the invention of the Zombie. In these fifty years, let’s face it, we have been completely overrun. Zombies are everywhere. They are in our movies, tv shows, books, and comic books, plus, out here in the real world where the Center for Disease Control has a comprehensive Zombie preparedness and education plan and there are Zombie-walks, Zombie-conventions, and, anyway, didn’t you see them this Halloween? The most popular Zombie tv show, “The Walking Dead”, has been streaming for almost ten years – and the comic book it is based on is still going strong. At least one Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winning author has written a straight-up zombie novel – Colson Whitehead’s “Zone One”. So, what’s with all the Zombies?

“They all go the same way. Look up, then down and to the left,” the EMT said. “Always.”

“They all go the same way. Look up, then down and to the left,” the EMT said. “Always.”