by Pranab Bardhan

In the next couple of months two of the largest democracies in the world—India and Indonesia—will have their national elections. At a time when democracy is under considerable pressure everywhere, the electoral and general democratic outcome in these two countries containing in total more than one and a half billion people (more than one and a half times the population in democratic West plus Japan and Australia) will be closely observed.

In the next couple of months two of the largest democracies in the world—India and Indonesia—will have their national elections. At a time when democracy is under considerable pressure everywhere, the electoral and general democratic outcome in these two countries containing in total more than one and a half billion people (more than one and a half times the population in democratic West plus Japan and Australia) will be closely observed.

Let’s start with India. Many Indians, while preening about their country being the largest democracy, are often in denial about how threadbare the quality of that democracy actually has been, particularly in recent years. Indian elections are vigorous (barring some occasional complaints about intimidations and irregularities) and largely competitive (the Indian electorate is usually more anti-incumbent than, say, the American). But other essential aspects of democracy—respect for basic civic and human rights and established procedures of accountability in day-to-day governance—are quite weak. (I don’t like the oxymoronic term ‘illiberal democracy’, used by many people—from Fareed Zakaria to Viktor Orban—as this ignores those essential aspects of democracy).

In India (as in Indonesia) democracy is often mis-identified with a kind of crude majoritarianism. The Hindu nationalists which currently rule India often trample on minority rights with shameless impunity. They have created an atmosphere of hateful violence and intimidation against dissidents and minorities, where freedom of expression by artists, writers, scholars, journalists and others is routinely violated. Supposed “group rights” trump individual rights: individual freedom of expression has very little chance if some group claims to take offence. Courts sometimes take redemptive action, usually with great delay, but meanwhile the damage is done in intimidating large numbers of people. Read more »

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.

I was struck by a sentence in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book: “If nothing lasts, nothing matters.” This line was part of a discussion of memory, the fear of being forgotten, and the value of passing things on to future generations. I share a passion for the idea of continuity between generations (and I highly recommend Orlean’s book), but ultimately I don’t think that something has to last to matter. Alan Watts, in his book This Is It, says that “This—the immediate, everyday, and present experience—is IT, the entire and ultimate point for the existence of a universe.” It’s not about connecting with anything but what’s here in front of me now. (Easier said than done, of course.)

I was struck by a sentence in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book: “If nothing lasts, nothing matters.” This line was part of a discussion of memory, the fear of being forgotten, and the value of passing things on to future generations. I share a passion for the idea of continuity between generations (and I highly recommend Orlean’s book), but ultimately I don’t think that something has to last to matter. Alan Watts, in his book This Is It, says that “This—the immediate, everyday, and present experience—is IT, the entire and ultimate point for the existence of a universe.” It’s not about connecting with anything but what’s here in front of me now. (Easier said than done, of course.) I teach two kinds of group exercise classes, and part of the certification processes for both disciplines devoted no small amount of attention to how to speak to your minions, uh, students.

I teach two kinds of group exercise classes, and part of the certification processes for both disciplines devoted no small amount of attention to how to speak to your minions, uh, students. “…And now to introduce our second panelist: Martha. Martha does believe that academic philosophy is worth pursuing, and she has – of course – written a book about it. Martha, can you briefly summarize your argument?”

“…And now to introduce our second panelist: Martha. Martha does believe that academic philosophy is worth pursuing, and she has – of course – written a book about it. Martha, can you briefly summarize your argument?”

My answering machine whirrs. From an echoing room, the chainsaw-voice shouts into a speaker phone:

My answering machine whirrs. From an echoing room, the chainsaw-voice shouts into a speaker phone: One of the philosophical tools that seems utterly obvious to me is the so-called “use/mention distinction”. Because it strikes me as so obvious, it is always baffling to me that people seem to have such trouble with it.

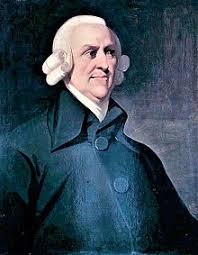

One of the philosophical tools that seems utterly obvious to me is the so-called “use/mention distinction”. Because it strikes me as so obvious, it is always baffling to me that people seem to have such trouble with it. I just read Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations for the first time. Not every word. It’s over a thousand pages, and there are long “Digressions” (Smith’s term) on matters such as the history of the value of silver, or banking in Amsterdam, which I simply passed over. I was mainly interested in what Smith has to say about work, so I also merely skimmed some other sections that seemed to have little relevance to my research. Time and again, though, I found myself getting sucked into chapters unrelated to my concerns simply because the topics discussed are so interesting, and what Smith has to say is so thought-provoking. Reading the book is also made easier both by Smith’s admirably lucid writing and by the brief summaries of the main claims being made that he inserts throughout at the left-hand margin.

I just read Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations for the first time. Not every word. It’s over a thousand pages, and there are long “Digressions” (Smith’s term) on matters such as the history of the value of silver, or banking in Amsterdam, which I simply passed over. I was mainly interested in what Smith has to say about work, so I also merely skimmed some other sections that seemed to have little relevance to my research. Time and again, though, I found myself getting sucked into chapters unrelated to my concerns simply because the topics discussed are so interesting, and what Smith has to say is so thought-provoking. Reading the book is also made easier both by Smith’s admirably lucid writing and by the brief summaries of the main claims being made that he inserts throughout at the left-hand margin.