by Thomas O’Dwyer

“There is no question I love her deeply … I keep remembering her body, her nakedness, the day with her, our bottle of champagne … She says she thinks of me all the time (as I do of her) and her only fear is that being apart, we may gradually cease to believe that we are loved, that the other’s love for us goes on and is real. As I kissed her she kept saying, ‘I am happy, I am at peace now.’ And so was I.”

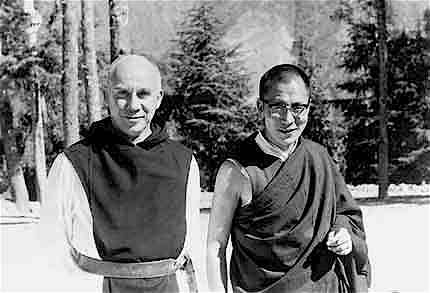

These romantic diary entries of a middle-aged man smitten with a new love would seem unremarkable, commonplace, but for one thing. The author was a Trappist monk, a priest in one of the most strict Catholic monastic orders, bound by vows of poverty, chastity, obedience and silence. Moreover, he was world famous in his monkishness as the author of best-selling books on spirituality, monastic vocation and contemplation. He was credited with drawing vast numbers of young men into seminaries around the world during the last modern upsurge of religious fervour after World War II. Two years after this tryst, the world’s most famous monk was found dead in a room near a conference centre in Bangkok, Thailand. He was on his back, wearing only shorts, electrocuted by a Hitachi floor-fan lying on his chest. In the tabloids there were dark mutterings of divine retribution, suicide, even a CIA murder conspiracy.

So passed Thomas Merton, who shot to fame in 1948 when he published his memoir The Seven Storey Mountain. It was the tale of a journey from a life of “beer, bewilderment, and sorrow” to a seminary in the Order of Cistercians of Strict Observance, commonly known as Trappists. A steady output of books, essays and poems made him one of the best known and loved spiritual writers of his day. It also made millions of dollars for his Trappist monastery, the Abbey of Gethsemani in Nelson county, Kentucky. Because of him, droves of demobbed soldiers and marines clamoured to become monks. Read more »

The spring ephemeral wildflowers of the Midwest are generally not large or showy. In a relatively short time during one of the less promising parts of the year, these perennial plants must put out leaves and flowers and reproduce, all before disappearing until the next spring. Still, they light up the woods for me every year despite their relatively modest circumstances.

The spring ephemeral wildflowers of the Midwest are generally not large or showy. In a relatively short time during one of the less promising parts of the year, these perennial plants must put out leaves and flowers and reproduce, all before disappearing until the next spring. Still, they light up the woods for me every year despite their relatively modest circumstances.

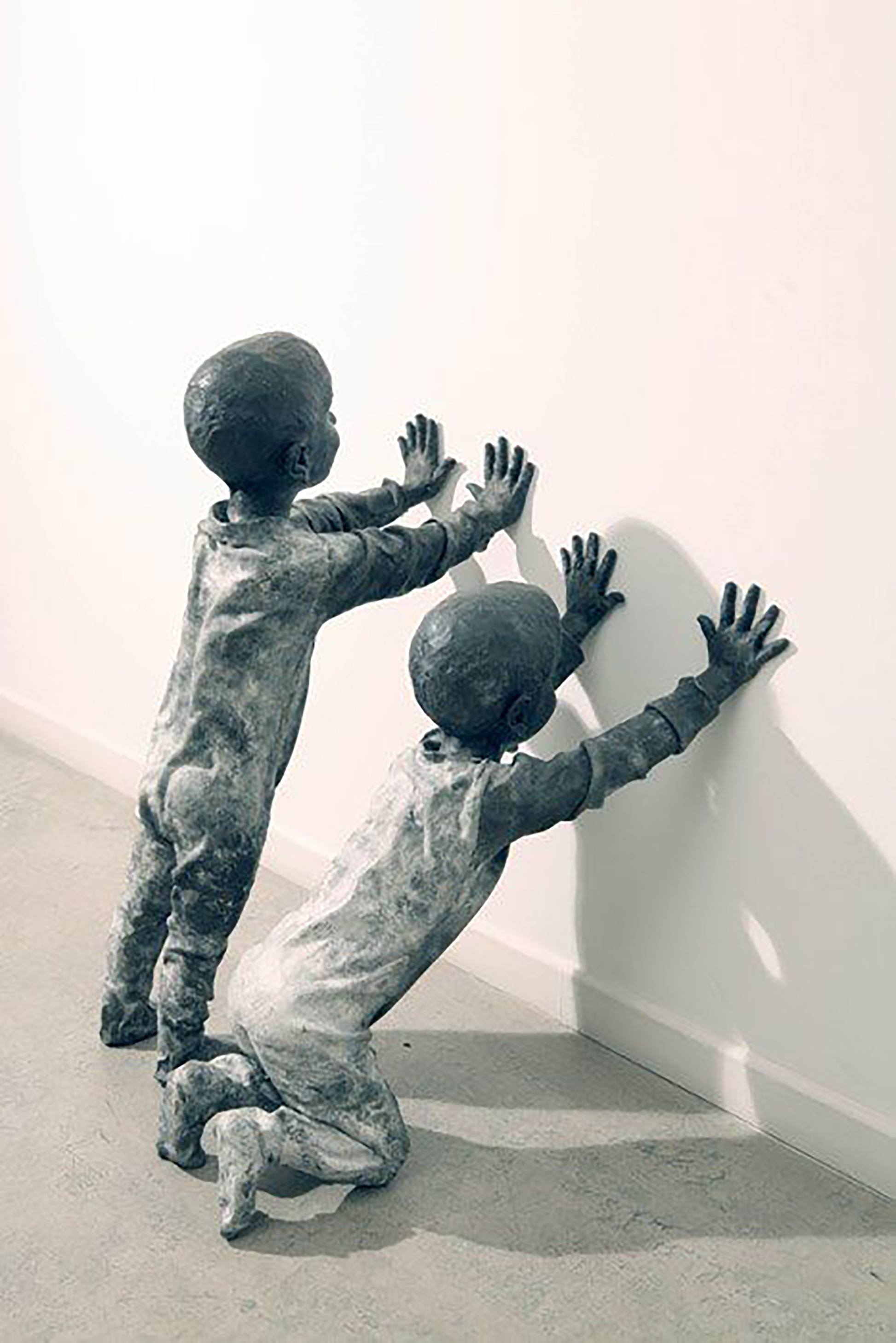

When Socrates’ students enter his cell, in subdued spirits, their mentor has just been released from his shackles. After having his wife and baby sent away, Socrates spends some time sitting up on the bed, rubbing his leg, cheerfully remarking on how it feels much better now, after the pain.

When Socrates’ students enter his cell, in subdued spirits, their mentor has just been released from his shackles. After having his wife and baby sent away, Socrates spends some time sitting up on the bed, rubbing his leg, cheerfully remarking on how it feels much better now, after the pain.

I’ve always liked stories that depended on mistaken identity, a very old theme in general. Having a degree in mathematical logic, I was also drawn to the subject on a more theoretical level, on which lies Gettier’s Paradox.

I’ve always liked stories that depended on mistaken identity, a very old theme in general. Having a degree in mathematical logic, I was also drawn to the subject on a more theoretical level, on which lies Gettier’s Paradox.

Movies, music and novels portray a particular ideal of romantic love almost relentlessly. Love is something that happens to you, something you fall into even against your will or better judgement. It is something to be experienced as good in itself and joyfully submitted to, not something that should be questioned.

Movies, music and novels portray a particular ideal of romantic love almost relentlessly. Love is something that happens to you, something you fall into even against your will or better judgement. It is something to be experienced as good in itself and joyfully submitted to, not something that should be questioned.

Just as Anteus in Greek mythology renewed his strength by touching the earth, so emigrés who live abroad often draw some sort of cultural or spiritual nourishment from returning to their roots. In my case this means returning to Britain, and specifically to the countryside that remains, for the most part, green and pleasant. Usually I do this in the summer, so it made a nice change this year to be in Britain at the beginning of Spring. The trees not yet being in leaf left more of the landscape open and visible. There were fewer flowers, of course, but there were also fewer holiday makers clogging up the roads and the honey pot tourist sites.

Just as Anteus in Greek mythology renewed his strength by touching the earth, so emigrés who live abroad often draw some sort of cultural or spiritual nourishment from returning to their roots. In my case this means returning to Britain, and specifically to the countryside that remains, for the most part, green and pleasant. Usually I do this in the summer, so it made a nice change this year to be in Britain at the beginning of Spring. The trees not yet being in leaf left more of the landscape open and visible. There were fewer flowers, of course, but there were also fewer holiday makers clogging up the roads and the honey pot tourist sites.

The wine world thrives on variation. Wine grapes are notoriously sensitive to differences in climate, weather and soil. If care is taken to plant grapes in the right locations and preserve those differences, each region, each vintage, and indeed each vineyard can produce differences that wine lovers crave. If the thousands of bottles on wine shop shelves all taste the same, there is no justification for the vast number of brands and their price differentials. Yet the modern wine world is built on processes that can dampen variation and increase homogeneity. If these processes were to gain power and prominence the culture of wine would be under threat. The wine world is a battleground in which forces that promote homogeneity compete with forces that encourage variation with the aesthetics of wine as the stakes. In order to understand the nature of the threat homogeneity poses to the wine world and the reasons why thus far we’ve avoided the worst consequences of that threat we need to understand these forces. I will be telling this story from the perspective of the U.S. although the themes will resonate within wine regions throughout much of the world.

The wine world thrives on variation. Wine grapes are notoriously sensitive to differences in climate, weather and soil. If care is taken to plant grapes in the right locations and preserve those differences, each region, each vintage, and indeed each vineyard can produce differences that wine lovers crave. If the thousands of bottles on wine shop shelves all taste the same, there is no justification for the vast number of brands and their price differentials. Yet the modern wine world is built on processes that can dampen variation and increase homogeneity. If these processes were to gain power and prominence the culture of wine would be under threat. The wine world is a battleground in which forces that promote homogeneity compete with forces that encourage variation with the aesthetics of wine as the stakes. In order to understand the nature of the threat homogeneity poses to the wine world and the reasons why thus far we’ve avoided the worst consequences of that threat we need to understand these forces. I will be telling this story from the perspective of the U.S. although the themes will resonate within wine regions throughout much of the world. In May 2014, a young man beat his twenty-year-old sister, Farzana, to death by hitting her head with a brick. He did this in broad daylight just outside the High Court building in Lahore, the cultural, artistic and academic capital of Pakistan. He did it as local policemen and passersby looked on, lawyers in their black flowing robes went in and out of their offices and barely fifty yards away, inside the building, the bewigged and begowned Chief Justice sat with his hand on the polished gavel.

In May 2014, a young man beat his twenty-year-old sister, Farzana, to death by hitting her head with a brick. He did this in broad daylight just outside the High Court building in Lahore, the cultural, artistic and academic capital of Pakistan. He did it as local policemen and passersby looked on, lawyers in their black flowing robes went in and out of their offices and barely fifty yards away, inside the building, the bewigged and begowned Chief Justice sat with his hand on the polished gavel.