by Robert Fay

Kit Moresby, the enigmatic heroine of Paul Bowles’ novel The Sheltering Sky sits in a café in a French colonial city in North Africa. It’s 1949 (or thereabouts) and on the terrace Arab men wearing fezzes drink mineral water and swat flies. Kit and her American companions have just arrived by freighter and they sip Pernod and discuss their initial impressions. They are planning on traveling into the Bled, the vast interior, where they hope to find lands and people untouched by the war and the contaminates of European civilization.

These three are the opposite of the “ugly American” stereotype of the post-war era. They are pessimistic, worldly and bored with America. If anything, their Americanness is revealed in their unwillingness to accept that life and suffering could possibly be synonymous. They are world-weary Bohemians who recognize the America of the 1950s will be a consumer-orientated project. These characters are, in a certain sense, proto-Beats, and in fact the actual Beat writers, men like William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac admired Bowles and eventually befriended him.

“It seems as though there might be some place in the world they could have left alone,” Kit says. She is a woman of omens. A person of great strength, yet because of the restraints of the era, must admit “other people rule my life.” She wants to truly live, to push aside the veil separating her from raw experiences, but she is fearful and superstitious. “The people of each country get more like the people of every other country,” she says. “They have no character, no beauty, no ideals, no culture—nothing, nothing.” Read more »

Johnny spoke softly in a voice just past the threshold of manhood. His smile, mistaken for charm, was longing. I could see the pentimento of the child still in him.

Johnny spoke softly in a voice just past the threshold of manhood. His smile, mistaken for charm, was longing. I could see the pentimento of the child still in him.

It does not take long for history to repeat itself. It was only a little over a decade ago that overzealous lending, lax underwriting standards, unrealistic collateral valuations, borrowers not understanding loan terms, an exploding derivative securities market–and a dozen or so other factors–led to a massive crash in the housing market. Today in the United States we have outstanding student loan debt of $1.5

It does not take long for history to repeat itself. It was only a little over a decade ago that overzealous lending, lax underwriting standards, unrealistic collateral valuations, borrowers not understanding loan terms, an exploding derivative securities market–and a dozen or so other factors–led to a massive crash in the housing market. Today in the United States we have outstanding student loan debt of $1.5

While Trump’s immigration politics makes international headlines almost every day, the disaster of the European immigration policies rarely becomes international news. A recent exception is the case of Captain Carola Rackete, and it is a telling one. With all the potential for a good story, Rackete’s journey is both standing for and at the same time distracting from the actual complex mess of European immigration politics.

While Trump’s immigration politics makes international headlines almost every day, the disaster of the European immigration policies rarely becomes international news. A recent exception is the case of Captain Carola Rackete, and it is a telling one. With all the potential for a good story, Rackete’s journey is both standing for and at the same time distracting from the actual complex mess of European immigration politics. When the flight delay is announced, we ask what it is we have done wrong. From airlines and the world at large, the answer is rarely forthcoming, so we must look inward instead.

When the flight delay is announced, we ask what it is we have done wrong. From airlines and the world at large, the answer is rarely forthcoming, so we must look inward instead.

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

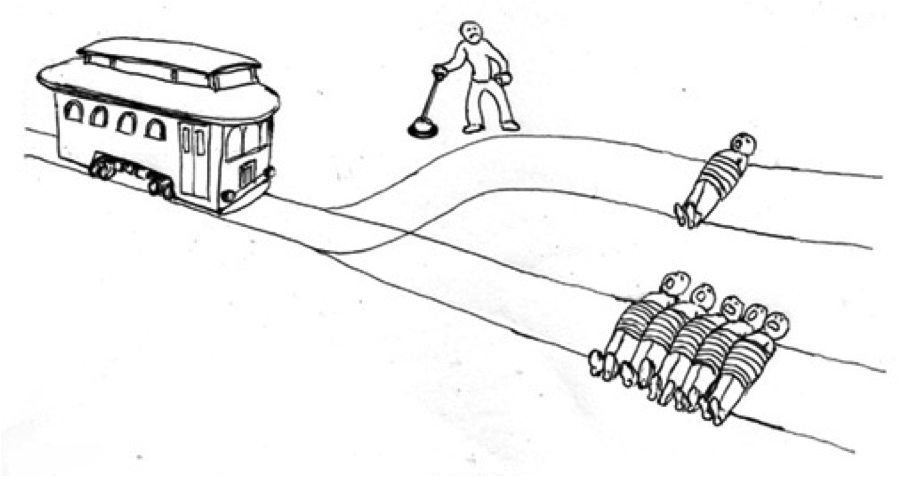

In “The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values” Sam Harris argues that the morally right thing to do is whatever maximizes the welfare or flourishing of human beings. Science “determines human values”, he says, by clarifying what that welfare or flourishing consists of exactly. In an early footnote he complains that “Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature on moral philosophy.” But he did not do so, he explains, for two reasons. One is that he did not arrive at his position by reading philosophy, he just came up with it, all on his own, from scratch. The second is because he “is convinced that every appearance of terms like…’deontology’”, etc. “increases the amount of boredom in the universe.”

In “The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values” Sam Harris argues that the morally right thing to do is whatever maximizes the welfare or flourishing of human beings. Science “determines human values”, he says, by clarifying what that welfare or flourishing consists of exactly. In an early footnote he complains that “Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature on moral philosophy.” But he did not do so, he explains, for two reasons. One is that he did not arrive at his position by reading philosophy, he just came up with it, all on his own, from scratch. The second is because he “is convinced that every appearance of terms like…’deontology’”, etc. “increases the amount of boredom in the universe.”

A British friend of mine once told me that when he feels stressed he often turns to re-reading R.K. Narayan’s stories about Malgudi, the fictional placid small town in south India. Much earlier, in the 1930’s, a fellow-Britisher, the writer Graham Greene, had discovered Narayan and became his life-long friend, mentor, agent for the wider literary world, and even occasional proof-reader. He found a kind of ‘sadness and beauty’ in Narayan’s simple depiction of the idiosyncrasies and disappointments of ordinary lives which he imbues with a touching sense of gentle irony and compassion.

A British friend of mine once told me that when he feels stressed he often turns to re-reading R.K. Narayan’s stories about Malgudi, the fictional placid small town in south India. Much earlier, in the 1930’s, a fellow-Britisher, the writer Graham Greene, had discovered Narayan and became his life-long friend, mentor, agent for the wider literary world, and even occasional proof-reader. He found a kind of ‘sadness and beauty’ in Narayan’s simple depiction of the idiosyncrasies and disappointments of ordinary lives which he imbues with a touching sense of gentle irony and compassion. I shall start with the third, titled Between the Assassinations by Aravind Adiga, which is probably the furthest of the three in terms of dissonance from the life in Malgudi. Here we can definitely say: Toto, we are not in Malgudi anymore. The assassinations referred to are those of Indira Gandhi in 1984 and of her son, Rajiv Gandhi, in 1991, but in the book except for merely as a time-marker of those 7 years, they do not play any direct role. Adiga came to be widely noted after he won the Booker Prize for his short novel The White Tiger, a book of stridently raging fury at the crushing inequalities and depravity arising from India’s roaring economic growth and somewhat cardboard characters through which they are played out, a book I did not particularly like. Adiga wrote Between the Assassinations earlier but published it after The White Tiger. Here the fury is less strident, there is more nuance and variety in the characters, and along with aching sympathy there is all-enveloping hopelessness. Here is a typical scene: a lowly cart-rickshaw puller, straining hard going uphill with a heavy load, exhausted by the heat and humiliation and a painful neck, stops his cart in the middle of the busy road, shakes his fist in a futile gesture at the passing, honking traffic and shouts: ‘Don’t you see something is wrong with this world?’

I shall start with the third, titled Between the Assassinations by Aravind Adiga, which is probably the furthest of the three in terms of dissonance from the life in Malgudi. Here we can definitely say: Toto, we are not in Malgudi anymore. The assassinations referred to are those of Indira Gandhi in 1984 and of her son, Rajiv Gandhi, in 1991, but in the book except for merely as a time-marker of those 7 years, they do not play any direct role. Adiga came to be widely noted after he won the Booker Prize for his short novel The White Tiger, a book of stridently raging fury at the crushing inequalities and depravity arising from India’s roaring economic growth and somewhat cardboard characters through which they are played out, a book I did not particularly like. Adiga wrote Between the Assassinations earlier but published it after The White Tiger. Here the fury is less strident, there is more nuance and variety in the characters, and along with aching sympathy there is all-enveloping hopelessness. Here is a typical scene: a lowly cart-rickshaw puller, straining hard going uphill with a heavy load, exhausted by the heat and humiliation and a painful neck, stops his cart in the middle of the busy road, shakes his fist in a futile gesture at the passing, honking traffic and shouts: ‘Don’t you see something is wrong with this world?’