Joseph R. Bertino, MD, is University Professor of medicine and pharmacology, UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and has previously served as director of the Yale Cancer Center and chair of the Molecular Pharmacology and Therapeutics Program at Memorial Sloan-Kettering. He is the author and co-author of more than 400 scientific publications and the founding editor of the Journal of Clinical Oncology. His research is focused on curative treatments for leukemia and lymphoma and has helped shape optimal methotrexate administration schedules. Currently, his laboratory is studying gene therapy and stem cell research. He has received the Rosenthal Award from the American Association of Clinical Research, the Karnofsky Award from the American Society for Clinical Oncology, and the American Cancer Society Medal of Honor for his accomplishments in the field of research.

Azra Raza, author of the forthcoming book The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

As a child, author and poet Annie Dillard would traipse through her neighborhood, searching for ideal places to stash pennies where others might find them. In her novel

As a child, author and poet Annie Dillard would traipse through her neighborhood, searching for ideal places to stash pennies where others might find them. In her novel

Why do we value successful art works, symphonies, and good bottles of wine? One answer is that they give us an experience that lesser works or merely useful objects cannot provide—an aesthetic experience. But how does an aesthetic experience differ from an ordinary experience? This is one of the central questions in philosophical aesthetics but one that has resisted a clear answer. Although we are all familiar with paradigm cases of aesthetic experience—being overwhelmed by beauty, music that thrills, waves of delight provoked by dialogue in a play, a wine that inspires awe—attempts to precisely define “aesthetic experience” by showing what all such experiences have in common have been less than successful.

Why do we value successful art works, symphonies, and good bottles of wine? One answer is that they give us an experience that lesser works or merely useful objects cannot provide—an aesthetic experience. But how does an aesthetic experience differ from an ordinary experience? This is one of the central questions in philosophical aesthetics but one that has resisted a clear answer. Although we are all familiar with paradigm cases of aesthetic experience—being overwhelmed by beauty, music that thrills, waves of delight provoked by dialogue in a play, a wine that inspires awe—attempts to precisely define “aesthetic experience” by showing what all such experiences have in common have been less than successful.

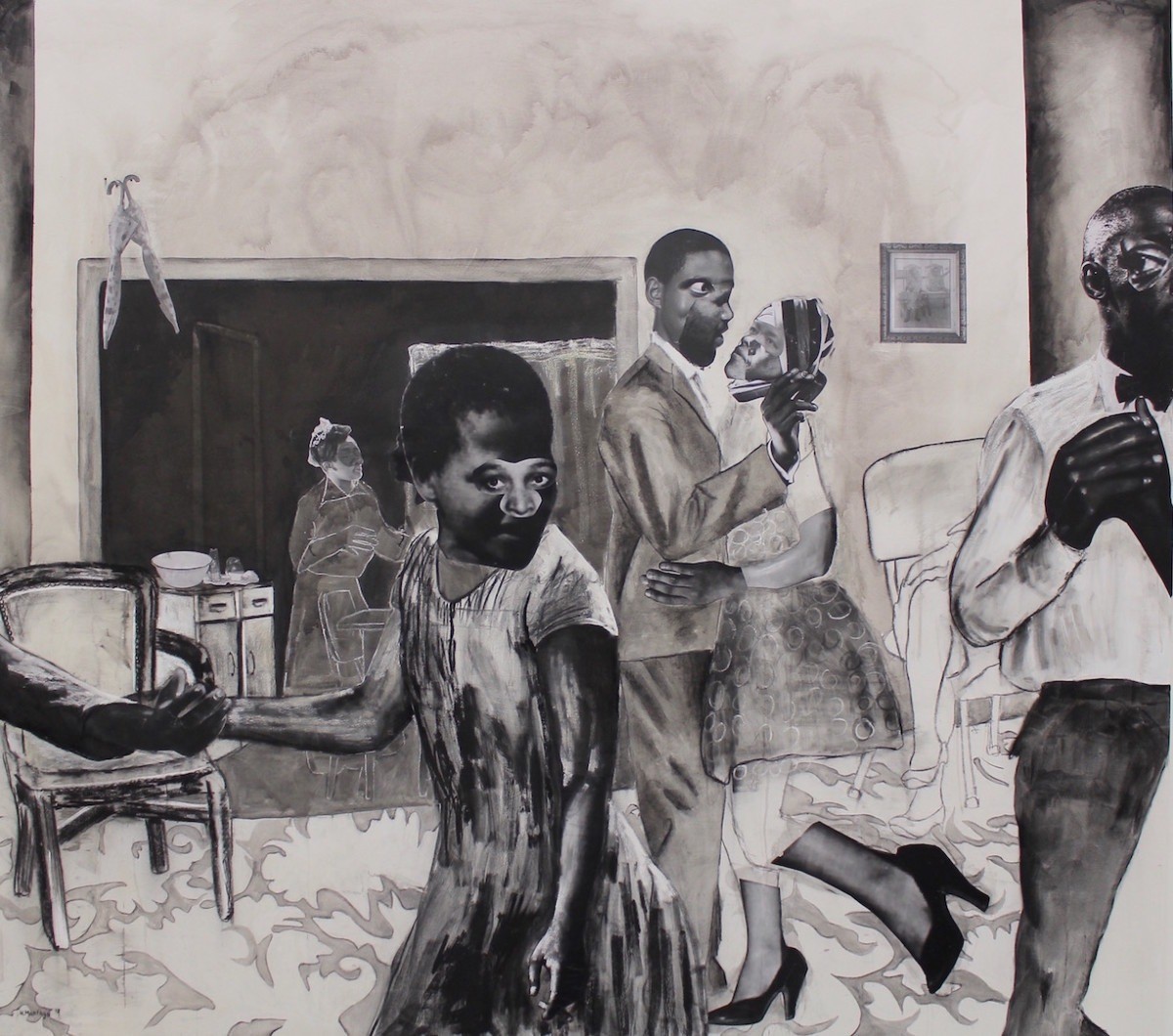

The apartment in West Harlem, five buildings down on the left. The apartment just past the pawn shop, across from the Rite-Aid, parallel to the barber’s where all the pretty boys hangout waiting to get a Friday night shave. The apartment past the deli were you get cheese and pickle sandwiches and the all-night liquor store and the ATM machine no one is dumb enough to use.

The apartment in West Harlem, five buildings down on the left. The apartment just past the pawn shop, across from the Rite-Aid, parallel to the barber’s where all the pretty boys hangout waiting to get a Friday night shave. The apartment past the deli were you get cheese and pickle sandwiches and the all-night liquor store and the ATM machine no one is dumb enough to use.

I don’t know a lot about guns.

I don’t know a lot about guns.

Smacked my head on the pavement while jogging across campus in the rain. Had my hands on my stomach, holding documents in place underneath my shirt to keep them dry. So when my foot went out after skipping over a puddle, I couldn’t get my front paws down in time to brace my fall as I corkscrewed through the air, landing on my hip and shoulder, and whiplashing my head downward. Consequently I don’t have the brain power to crank out 2,000 fresh words. So here’s a dated piece about Baby Boomer navel gazing and ressentiment.

Smacked my head on the pavement while jogging across campus in the rain. Had my hands on my stomach, holding documents in place underneath my shirt to keep them dry. So when my foot went out after skipping over a puddle, I couldn’t get my front paws down in time to brace my fall as I corkscrewed through the air, landing on my hip and shoulder, and whiplashing my head downward. Consequently I don’t have the brain power to crank out 2,000 fresh words. So here’s a dated piece about Baby Boomer navel gazing and ressentiment.

Thirty years ago this week two million people joined hands forming a human chain across 676 kilometers of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Known as the

Thirty years ago this week two million people joined hands forming a human chain across 676 kilometers of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Known as the  I’ve just come back from a lovely vacation in Ireland. We did a lot of driving and usually had the radio on, often to RTE, the state run station (the equivalent to the BBC in the UK). At least once an hour an advertisement would come on reminding people that they need to get a TV license, which costs 160 Euros, $177 a year. I grew up in the UK, where a license is 154.50 sterling, $187 a year, and remember the ads when I was a child that warned of the TV detector van coming around and catching people who hadn’t paid their license. Of course, that was in the days of very obvious exterior antennas on houses. When TV licenses were first issued in the UK after the second world war, they funded the single BBC channel. Even when I was a child, there were only 3 channels, then when I was a teen 4, and two of those were the BBC. In the UK today, a license is needed for any device that is

I’ve just come back from a lovely vacation in Ireland. We did a lot of driving and usually had the radio on, often to RTE, the state run station (the equivalent to the BBC in the UK). At least once an hour an advertisement would come on reminding people that they need to get a TV license, which costs 160 Euros, $177 a year. I grew up in the UK, where a license is 154.50 sterling, $187 a year, and remember the ads when I was a child that warned of the TV detector van coming around and catching people who hadn’t paid their license. Of course, that was in the days of very obvious exterior antennas on houses. When TV licenses were first issued in the UK after the second world war, they funded the single BBC channel. Even when I was a child, there were only 3 channels, then when I was a teen 4, and two of those were the BBC. In the UK today, a license is needed for any device that is