by Abigail Akavia

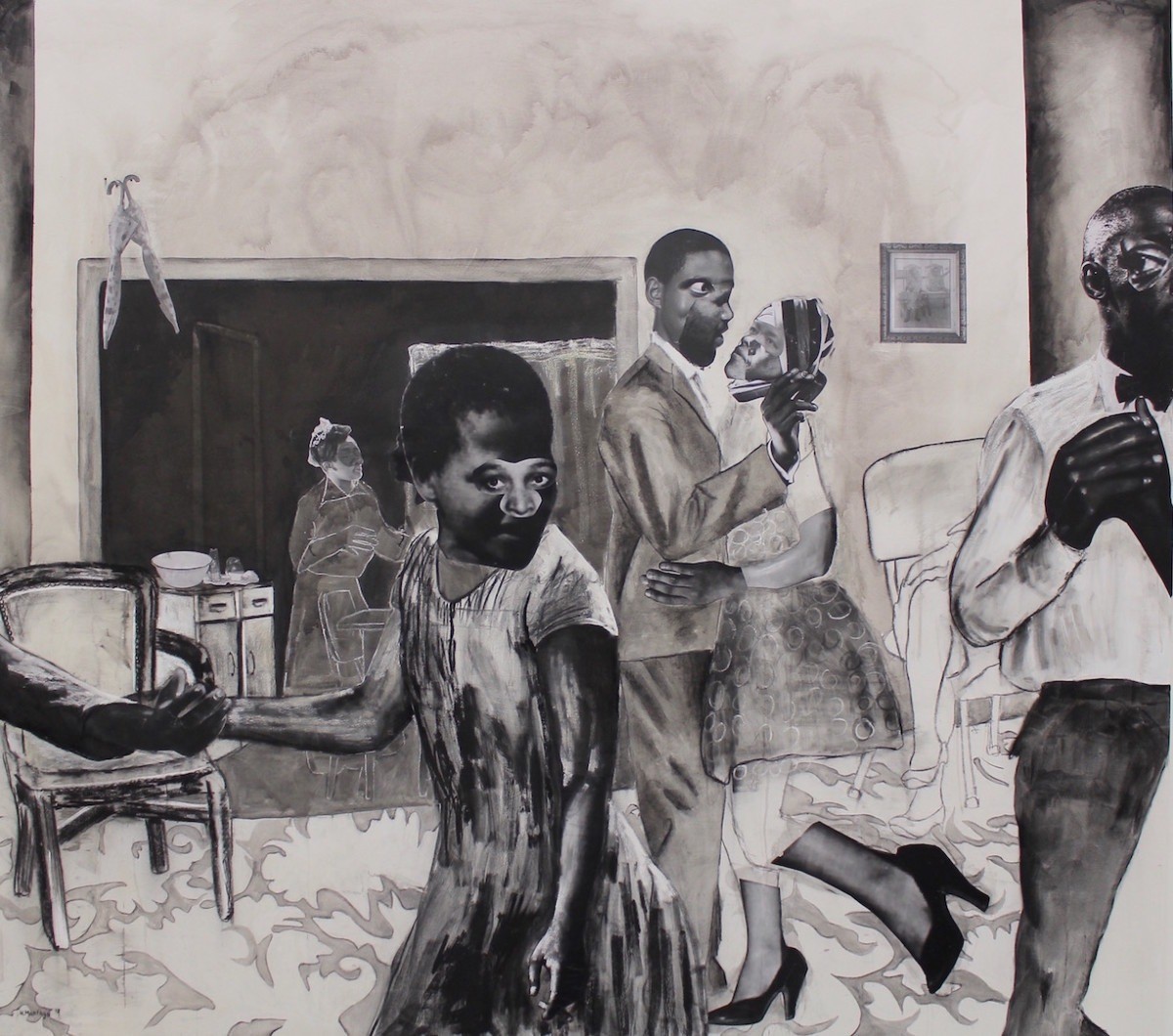

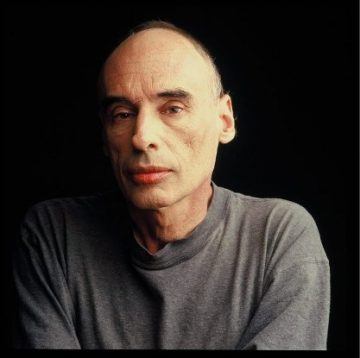

This month marks the twentieth anniversary of the death of Hanoch Levin. Levin was Israel’s most important and prolific playwright. In addition to 56 plays, most of which he directed himself, he wrote poems, sketches, and prose, and is often compared to such giants of modernism and absurd theater as Chekhov, Artaud, Brecht, and Beckett. Levin died of cancer at the age of 55, after gaining a unique status as a theatrical superstar. His plays were extremely popular, and some of the most significant works of Israeli high-culture ever produced.

Levin was catapulted into fame (or notoriety) as a satirist in the late 1960s. His scathing political pieces lampooned Israel’s chauvinistic patriotism at a time when the young state was overwhelmingly euphoric from its triumph against three Arab nations in the Six Day War. After these controversial satires, he wrote mostly comedies. Featuring pathetic but endearing characters with hilarious, often made-up, names—Jonah Popoch, David Leidenthal, Pepchetz Schitz, to mention just a few whose names are not too hard to translate or transliterate—his comedies represented a specific kind of Israeli Jew of east-European descent. At the same time, these comic figures stand for a broader Israeliness (not ethnic-specific, that is), which Levin exposed in its provinciality, illusions of grandeur, and a bigoted us-against-them mentality. Read more »

A recent article by Jane Mayer in The New Yorker, “The Case of Al Franken,”

A recent article by Jane Mayer in The New Yorker, “The Case of Al Franken,”

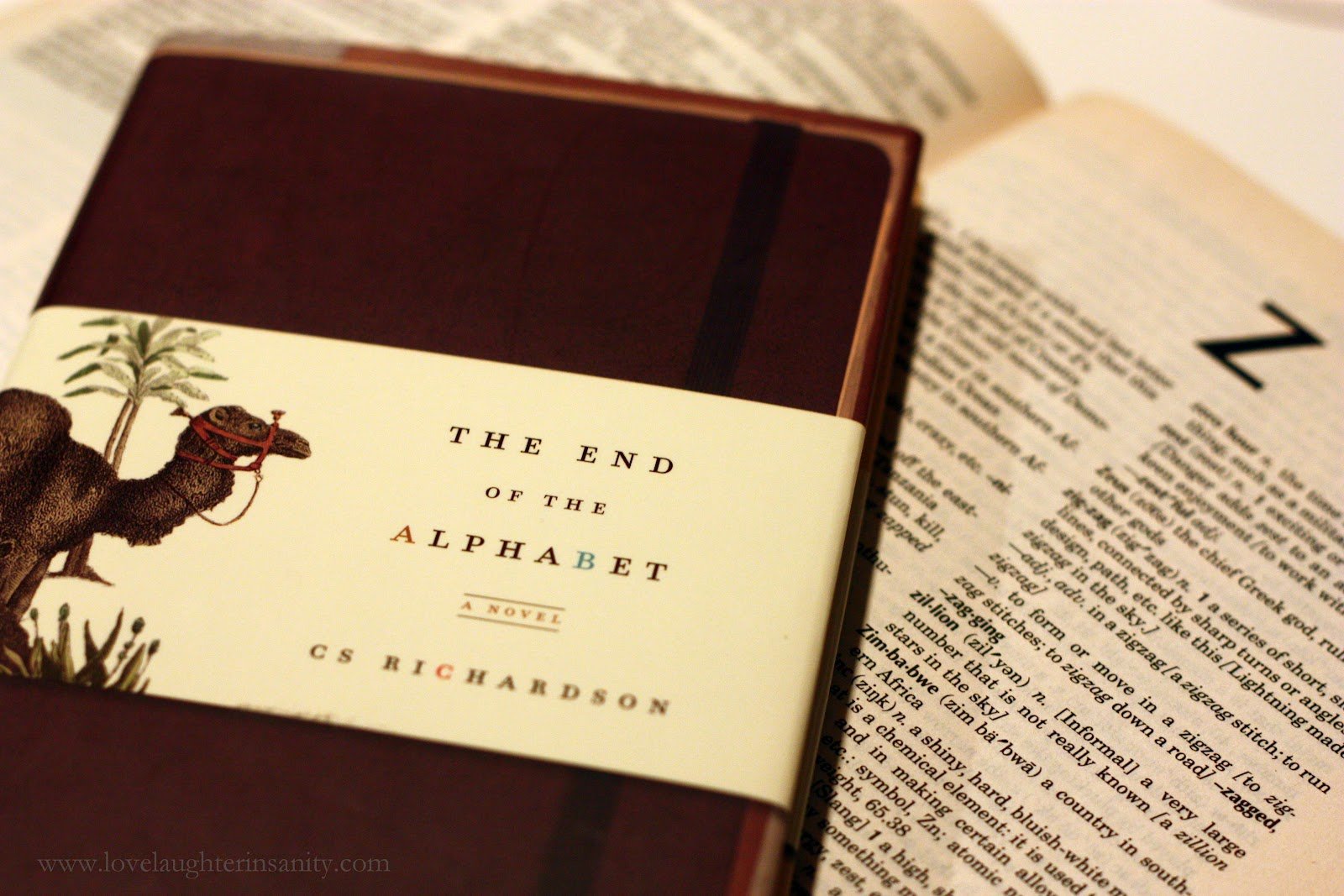

Ambrose finds out he has only weeks to live. How to spend that time is the premise of The End of the Alphabet (2007). It’s a condensed weepie in which Ambrose decides to visit a series of places with his wife that will take them through the alphabet. Somehow Richardson manages to stick to a minimalist elegance which probably saves the book from being schmaltzy book club fodder. And heck, you’d almost look forward to dying the way it’s put. Bucket list: die like this.

Ambrose finds out he has only weeks to live. How to spend that time is the premise of The End of the Alphabet (2007). It’s a condensed weepie in which Ambrose decides to visit a series of places with his wife that will take them through the alphabet. Somehow Richardson manages to stick to a minimalist elegance which probably saves the book from being schmaltzy book club fodder. And heck, you’d almost look forward to dying the way it’s put. Bucket list: die like this.

As a child, author and poet Annie Dillard would traipse through her neighborhood, searching for ideal places to stash pennies where others might find them. In her novel

As a child, author and poet Annie Dillard would traipse through her neighborhood, searching for ideal places to stash pennies where others might find them. In her novel

Why do we value successful art works, symphonies, and good bottles of wine? One answer is that they give us an experience that lesser works or merely useful objects cannot provide—an aesthetic experience. But how does an aesthetic experience differ from an ordinary experience? This is one of the central questions in philosophical aesthetics but one that has resisted a clear answer. Although we are all familiar with paradigm cases of aesthetic experience—being overwhelmed by beauty, music that thrills, waves of delight provoked by dialogue in a play, a wine that inspires awe—attempts to precisely define “aesthetic experience” by showing what all such experiences have in common have been less than successful.

Why do we value successful art works, symphonies, and good bottles of wine? One answer is that they give us an experience that lesser works or merely useful objects cannot provide—an aesthetic experience. But how does an aesthetic experience differ from an ordinary experience? This is one of the central questions in philosophical aesthetics but one that has resisted a clear answer. Although we are all familiar with paradigm cases of aesthetic experience—being overwhelmed by beauty, music that thrills, waves of delight provoked by dialogue in a play, a wine that inspires awe—attempts to precisely define “aesthetic experience” by showing what all such experiences have in common have been less than successful.

The apartment in West Harlem, five buildings down on the left. The apartment just past the pawn shop, across from the Rite-Aid, parallel to the barber’s where all the pretty boys hangout waiting to get a Friday night shave. The apartment past the deli were you get cheese and pickle sandwiches and the all-night liquor store and the ATM machine no one is dumb enough to use.

The apartment in West Harlem, five buildings down on the left. The apartment just past the pawn shop, across from the Rite-Aid, parallel to the barber’s where all the pretty boys hangout waiting to get a Friday night shave. The apartment past the deli were you get cheese and pickle sandwiches and the all-night liquor store and the ATM machine no one is dumb enough to use.

I don’t know a lot about guns.

I don’t know a lot about guns.