by Abigail Akavia

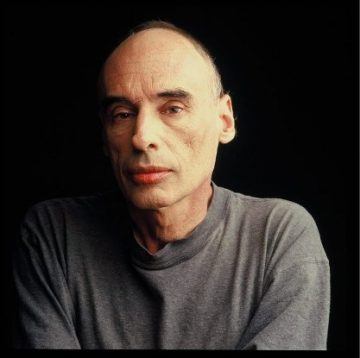

This month marks the twentieth anniversary of the death of Hanoch Levin. Levin was Israel’s most important and prolific playwright. In addition to 56 plays, most of which he directed himself, he wrote poems, sketches, and prose, and is often compared to such giants of modernism and absurd theater as Chekhov, Artaud, Brecht, and Beckett. Levin died of cancer at the age of 55, after gaining a unique status as a theatrical superstar. His plays were extremely popular, and some of the most significant works of Israeli high-culture ever produced.

Levin was catapulted into fame (or notoriety) as a satirist in the late 1960s. His scathing political pieces lampooned Israel’s chauvinistic patriotism at a time when the young state was overwhelmingly euphoric from its triumph against three Arab nations in the Six Day War. After these controversial satires, he wrote mostly comedies. Featuring pathetic but endearing characters with hilarious, often made-up, names—Jonah Popoch, David Leidenthal, Pepchetz Schitz, to mention just a few whose names are not too hard to translate or transliterate—his comedies represented a specific kind of Israeli Jew of east-European descent. At the same time, these comic figures stand for a broader Israeliness (not ethnic-specific, that is), which Levin exposed in its provinciality, illusions of grandeur, and a bigoted us-against-them mentality.

Some of Levin’s most important plays, aesthetically and philosophically speaking, are what are usually called his “myth plays”, plays based on Greek and Roman mythology or stories from the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. The explicitly universal frame of the myth-plays was used to explore human evil in its basest, most grotesque forms. The Torments of Job and The Great Whore of Babylon (a rewriting of the myth of Procne and Philomela), for example, present godless worlds where questions of morality are null, and a person’s happiness can only be gauged by their ability to inflect pain on others or to compare themselves to someone more miserable than them. These works put onstage horrific displays of suffering and torture, including outrageous sexual humiliation, and shy away from no bodily function, fluid, or waste.

The global appeal of his work can be understood through two myth-plays, one of which, The Moaners, is not even shockingly violent compared to Levin’s other works. The Moaners was written in the last year of Levin’s life, and he started (though did not complete) the process of casting, rehearsing, and meeting with designers while confined to his hospital bed. The play, combines two of Levin’s main genres—comedy and myth plays—can arguably be taken as a professional will and testament. The comedic portion is the setting and plot of the play itself: three dying men share a bed in a hospital in Calcutta, complaining of their pains and waiting for the end to come. The mythic portion is a play-within-a-play: the medical staff at the hospital present their patients with a performance of “The Sorrows and Death of Agamemnon”, a very condensed version of Aeschylus’ Agamemnon. The patients themselves take up the role of active spectators, a quasi-chorus which Levin calls “The People.” This setting is a means to expose the essential equivalence between the participants of the theatrical performance, active and passive alike—actors and audience members, heroes and nobodies.

In contrast to Levin’s other mythic plays, the suffering of the dying men is not inflicted upon them by anyone else; they simply experience the slow and inevitable disintegration of the body. The Moaners thus offers a distillation of Levin’s mythic theater: on the one hand, in the contemporary plot, the protagonists suffer, but since their pain is not due to the evil of others, it is not a matter of moral judgement. Life is presented as a truly universal succession of arbitrary suffering. On the other hand, in recreating Agamemnon, Levin not only chose a pinnacle of Athenian tragedy, but one of the foundational works of Western ethical thought, throughout which reverberates the notion that man’s suffering is a consequence of his actions and moral shortcomings.

Early on in The Moaners, the Old Nurse tells the Young Nurse that “learning comes from suffering”, literally echoing the famous pronouncement by the chorus of Agamemnon (pathei mathos in Greek). This she says to justify putting two dying men together in one bed: “There aren’t enough beds in Calcutta. Learn. Learning comes from suffering. And what do they care, they no longer feel anything. … And even if you crowd them together—they’re each to his own, alone.”[*] The two dramatic actions, the mythic and the comedic, climax in the death of their respective protagonists: Agamemnon is slain by his wife in retribution for his sacrifice of their daughter Iphigenia, while the character known as “Veteran Dying Men” (in contrast to his bed-mate New Dying Man, and Newest Dying Man who arrives late in the play), simply expires. The analogy between Agamemnon and Veteran Dying Man drives home Levin’s point, that the only truly important distinction is between the living and the dead. This view was clear already in Levin’s early satirical criticisms against Israel’s militaristic cult of heroism. Levin valued life above all else. For him, there was never a good reason to kill or to lose one’s life; death is a horror, never a deliverance, never a just sacrifice.

After bouts of pain, after sharing tears and roars of laughter with his bed-mate, Veteran Dying Man dies, a lonely anonymous man in a crowded third-world hospital. But his death is still one-of-a-kind. This is how it sounds in Levin’s stripped down poetic language:

Here it comes, the thing I waited for my whole life, […] it comes, and it is simple, and it comes just for me. Oh men, how will you understand?… Only the slightest touch, like a damp cloth sliding over a board, and the entire picture dissolves. Here it comes!…

The image of death as a damp cloth erasing a picture comes from Aeschylus’ Agamemnon. The seer Cassandra, the Trojan princess whom Agamemnon brought home as his bed-prize, likens men’s fortunes to a wiped-out image, just before entering the house where she will be murdered by Clytemnestra. This is not a pronouncement that Levin forgoes in his version—in fact, we hear it twice: once from Cassandra herself (played by the Young Nurse), and once again when Veteran Dying Man quotes Cassandra word for word. She is the character whose death itself and whose very understanding of death structures the entire play, with its seemingly incongruous parallel between heroic figures and anonymous dying men. Her prophetic vision of death as the grand equalizer between people becomes one of the programmatic statements in this play, a play entirely about death—and theater. If this is Levin’s will, then it is suggestive that Cassandra, whose prophecies were never believed but all came true, would be cast as his mouthpiece.

***

Levin had a special affinity with Aeschylus’ Cassandra. In the early 1980s Levin produced The Lost Women of Troy, an adaptation of Euripides’ Trojan Woman, in which he incorporated the Cassandra scene from Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, including these same words that are repeated in The Moaners. Life as an easily wiped out picture was an image Levin felt compelled to interpolate into his version of the capture and destruction of Troy. Euripides’ Trojan Woman shows the aftermath of the Trojan war from the perspective of Queen Hecuba and the captive women of Troy. Waiting to hear to which of the Greek commanders they will be allotted as war spoils, the women alternately lament, try to rationally make sense of their suffering, and are afflicted with more miseries. The play was first performed in 415 BCE, after the Athenians captured the island of Melos, executed the entire adult male population, and enslaved the women and children. The play has been received as a pronounced anti-war piece; since the early twentieth century, it has been repeatedly staged in areas reeling from violent conflict, and often adapted to reflect concrete modern war-zones. It is not surprising, then, that it also lent itself to Levin’s purposes in the wake of Israel’s involvement in South Lebanon.

The causes for this involvement stretch back to the mid 1970s. In the midst of a prolonged civil war between the Christian and Muslim populations of Lebanon, the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) gained prominence in the south of Lebanon, and began to attack Israeli communities near the northern border. Israel intervened in this internal conflict with support for the Christian civilian population as well as their militia. In the summer of 1982 the armed conflict between Israel and the PLO escalated, following an attempted assassination of Israel’s ambassador to the UK. This led, on June 6th, 1982, to the outbreak of what will later be known as The First Lebanon War, with a ground invasion of South Lebanon by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). IDF reached as far as Beirut, about 60 miles north of the border, and got progressively more embroiled in the internal conflict between Lebanese factions. One of the most brutal episodes of this war was the Sabra and Shatila massacre in mid-September, in which Christian militia fighters were allowed by IDF to independently “clear out” PLO fighters from the Sabra neighborhood of Beirut and the neighboring Shatila refugee camp. The action in fact consisted of a systematic, two-day massacre of the Palestinian and Shi’ite civilian population by Christian forces, with casualty estimates ranging from 460 to around three thousand. The IDF’s and the Israeli government’s failure to realize the consequences of the free reign they allowed the Christians—or, less controversially, their failure to intervene in the action once its reach became clear—was severely criticized, internally and internationally. The Sabra and Shatila massacre was a tipping point in Israeli public opinion against the involvement in Lebanon. Israeli troops withdrew from Beirut at the end of September 1982.

Levin wrote The Lost Women of Troy in 1981, and it premiered in Tel Aviv in February 1984. It follows the plot and structure of Euripides’ Trojan Women quite closely, and also draws on scenes from Euripides’ Hecuba, but ramps up the violence significantly. In Euripides, as per the conventions of ancient drama, violence is not showed onstage, but only reported by a “messenger.” This ubiquitous, often anonymous, fixture of Greek tragedy becomes a central figure in Euripides’ treatment of the Trojan war: the herald, Talthybius, is tasked with announcing every additional misfortune to Hecuba and to her daughters and daughters-in-law. One of these reports is the death of Polyxena. A daughter of Hecuba and Priam, she was sacrificed by the Greeks to appease the spirit of Achilles after he died in battle. Euripides treats this grim episode both in Trojan Women and in Hecuba, where Polyxena is presented as a heroic figure who went to her death unflinching, willingly choosing to be slain at Achilles’ tomb rather than become a slave. Levin’s world has no place for such self-sacrificial heroism: Polyxena exposes her breasts and says she is ready to be stricken (thus far, Levin follows Euripides). But before she can be “properly” slain, the swarm of soldiers lunge at her, and tear her body to shreds. This is Levin’s rendition of what the ancients viewed as a noble offering. His treatment of the Polyxena episode is a chilling vision of the barbaric capacities of men at war—even more chilling (and more visionary) if we remember that he wrote it before the Sabra and Shatila massacre took place. Levin exposes the sexual violence of the context (latent in the ancient Greek representation), where soldiers come in contact with civilian population. But most of all, he presents the death of civilians as an utterly savage, senseless atrocity. Using the framework of Greek myth without explicit references to contemporary events, Levin at once recalled World War II horrors, and foreshadowed the gory mess of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Upon hearing from Talthybius the narrative of her daughter’s death, Hecuba replies:

Were I asked yesterday what is a happy mother I would have answered: One whose children grow up, rich in good fortune and possessions, happily marry and produce rosy-cheeked heirs. Were you to ask me today what is a happy mother, I say: One who gets to bury her children in one piece.

“One who gets to bury her children in one piece”: my great-aunt, Zaharira Charifai, who originated the role of Hecuba in Levin’s version (and was a frequent actor in his plays) often quoted this passage to me once I started studying Classics. This was, to her, the essence of Greek tragedy, understood through the violence of Israeli society and modern warfare, and mediated through Hanoch Levin’s piercing vision: Hecuba lamenting the destruction of Troy—a mother mourning her children—and the power of theater to confront us with such violence and misery. Levin started out as Israeli theater’s trouble-maker and wonder-child, and was later one of the most celebrated Israeli artists of his generation. Nonetheless, throughout his career his voice was one of persistent, almost ruthless, criticism. In a rare interview from 1970 he said: I want to hit the audience, to show them how bad they are. But his plays are suffused with compassion and love of mankind. Because life, for him, is the only sacred thing there is.

[*] Translations of Levin’s texts quoted here courtesy of The Hanoch Levin Institute of Israeli Drama (with slight adaptations)