by Cathy Chua

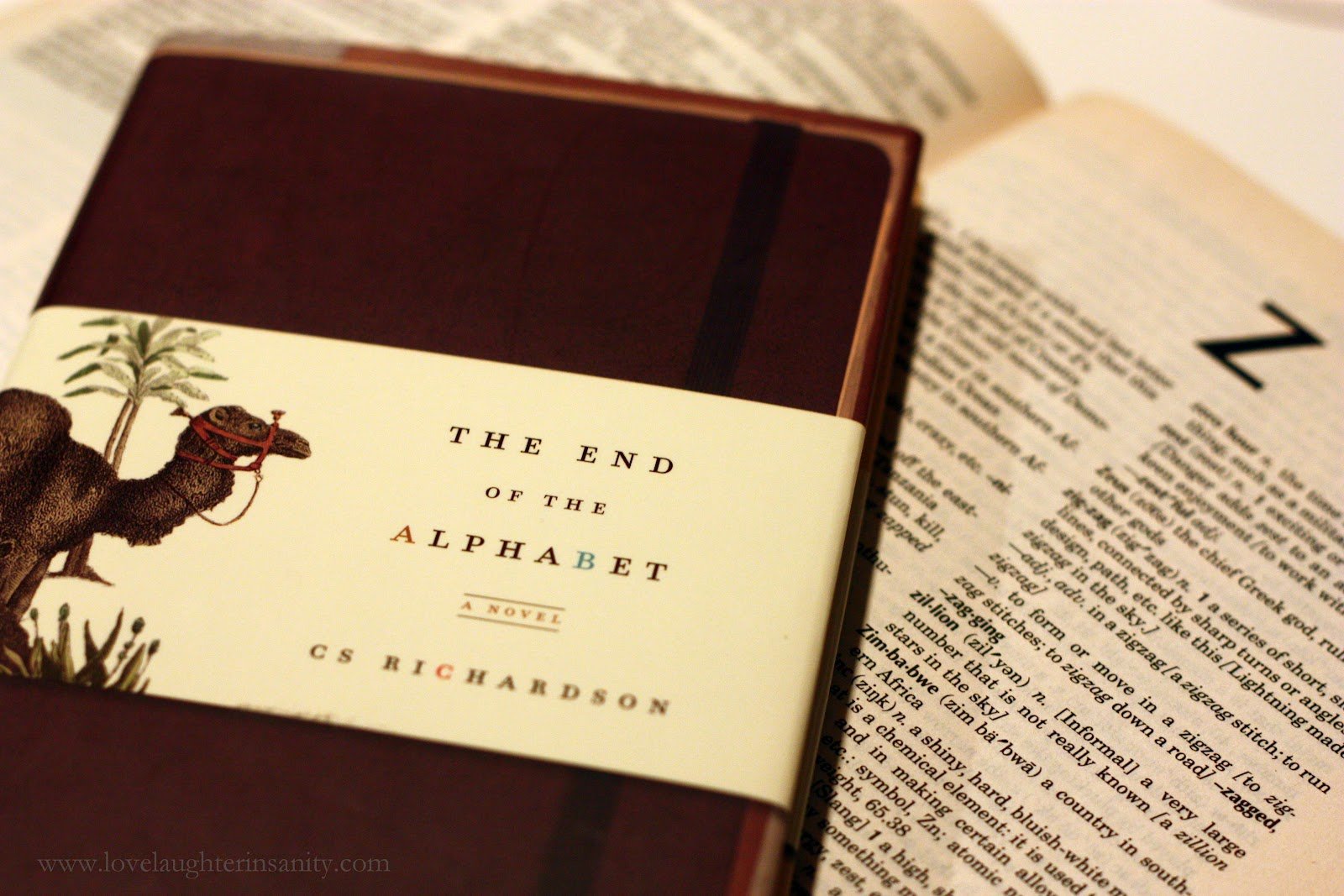

Ambrose finds out he has only weeks to live. How to spend that time is the premise of The End of the Alphabet (2007). It’s a condensed weepie in which Ambrose decides to visit a series of places with his wife that will take them through the alphabet. Somehow Richardson manages to stick to a minimalist elegance which probably saves the book from being schmaltzy book club fodder. And heck, you’d almost look forward to dying the way it’s put. Bucket list: die like this.

Ambrose finds out he has only weeks to live. How to spend that time is the premise of The End of the Alphabet (2007). It’s a condensed weepie in which Ambrose decides to visit a series of places with his wife that will take them through the alphabet. Somehow Richardson manages to stick to a minimalist elegance which probably saves the book from being schmaltzy book club fodder. And heck, you’d almost look forward to dying the way it’s put. Bucket list: die like this.

But then, there is real life. I’ve watched people who have been given a few weeks to live and it isn’t anything like art. My friend Richard found out in his mid-fifties. He’d complained about his stomach, been told there was nothing wrong, complained some more and was given the revised verdict. Pancreatic cancer, six weeks left. If it could be reassuring to be told this, he was advised that the first misdiagnosis didn’t matter. Richard spent what time he had left with his family: I felt guilt that we got to visit him for a precious hour. He was a Christian, maybe that inspired the serene and accepting way he set about his dying days.

I read The End of the Alphabet some years after Richard died. It didn’t give me any answers. How would I spend those last days of my life, should I be given that sentence? Perhaps it depends on the odds. Richard’s chances of survival were zero. What if you had ways of making that 1%? Would you take it? What would you be willing to pay to roll that dice?

There are a lot of ghosts in Geneva. It’s a town of transients, people blow in, make friends, blow out again. Mostly they leave you altogether at that point. The memories of these passing relationships are mainly neutral, even nice. But one of these ghosts truly haunts me. Just as Hendrik Sabroe lives with his disappeared wife and children in The Bridge (TV series), so I live with Genia. I met her on my first day in Geneva and over the years before she left we went to movies, concerts and many cafes. We’d knit and shoot the breeze about our shared passion for history. And although it’s been over three years since she was here, I see her everywhere all the time.

Like Richard, she knew something was wrong with her, but when she complained, towards the end of 2015, she was told the tests showed nothing. Upon complaining further, some weeks later, new tests were again negative. She was sent home once more, nothing wrong with her. But, like Richard, she knew that wasn’t so. If only doctors would trust their patients’ feelings. They did more tests in February when she complained yet again. Ah yes, they said to her. You have stage four secondary liver cancer and we don’t know what the primary is. That means we will only be guessing how to treat it. Was it an actual death sentence? Was Genia clutching at straws when she started chemo two days later or did she have a 1% chance?

I can say that Genia was the greatest fighter it has been my privilege to know. She wasn’t going to give up on one minute of life that could still be hers. She spent her last six weeks scared, but always hopeful. The fear was not obvious to those around her. I discovered it after her death when I went to her place to begin the process of sorting out what she had left. She wrote of her fear, as if by writing it down, she would exorcise it from her self. She did this by night in the dark. During daylight she planned her birthday, she saw her friends, she had her hair cut, she ate her beloved Russian dumplings. She continued to live alone in this period, though we had offered for her to stay with us.

She went back into hospital after six weeks to be informed that the first treatment had been completely pointless. Her tumour was worse. That was on a Friday. Nothing would be done for her until Monday, she was told. When, that is, the doctors would be back from their weekend. On Saturday evening she asked me to bring her some food and we watched her unable to keep it down. She had been in terrible pain for days, her liver was crushing her other organs. She refused the painkillers they wanted to give her. I was in denial. I didn’t realise that my last distressed words to her would be ‘Sweetheart, I’d give anything to be able to cook you something you could eat’. She went back to her bed. She was given massive doses of morphine during the night and she died the next day with her friends around her.

Genia did not make her 37th birthday. She was a talented historian doing a PhD, after receiving an award for her Masters. She had a shitty life from birth and continued to fight for better, whatever happened to her. I hope there is a parallel universe where people are meted out treatment according to what is fair. One where bad people pay for what they do and good people rule.

Meanwhile, I am left wondering. Will I go out with grace and dignity like Richard? Ferociously clinging on to every moment like Genia? Or will my exit be a piece of art, hopefully not conceived by Damien Hirst?