by Joshua Wilbur

This month I’m submitting a guest post written by an acquaintance of mine.

His name, strange as it may sound, is One-Week Man. He suffers from an unusual quirk: he can only remember the most recent week of his past, and he can only imagine one week into his future. He is forever stuck in this ever-shifting window of time.

One-Week Man is a bizarre, parochial soul, and I’m skeptical of his capacity to hold a well-informed opinion on anything of consequence. Nevertheless, he insisted on sharing his thoughts, which I present below, unedited.

It’s true. I can only recall one week of the past and think ahead one week into the future. (Maybe “Two-Week Man” would be a more fitting name, but I didn’t have much of a choice in the matter.)

Some explanation might be helpful. I’m writing this on a Sunday, September 1st. Exactly one week ago, I spent the day on the beach. What happened in my life prior to that sunny afternoon, I couldn’t tell you: it’s all a haze. Looking forward to next Sunday, I’m planning to do some work around the house, a one-bedroom cottage that I don’t remember moving into. Beyond that, I literally cannot imagine what the future holds. August 25th and September 8th represent the limits of my mental universe.

As it turns out, I’m very busy this week. My calendar—who would I be without it?—is filled with work meetings, doctors’ appointments, even an out-of-state conference from Wednesday to Friday. I work in the life insurance industry; I always have as far as I can tell.

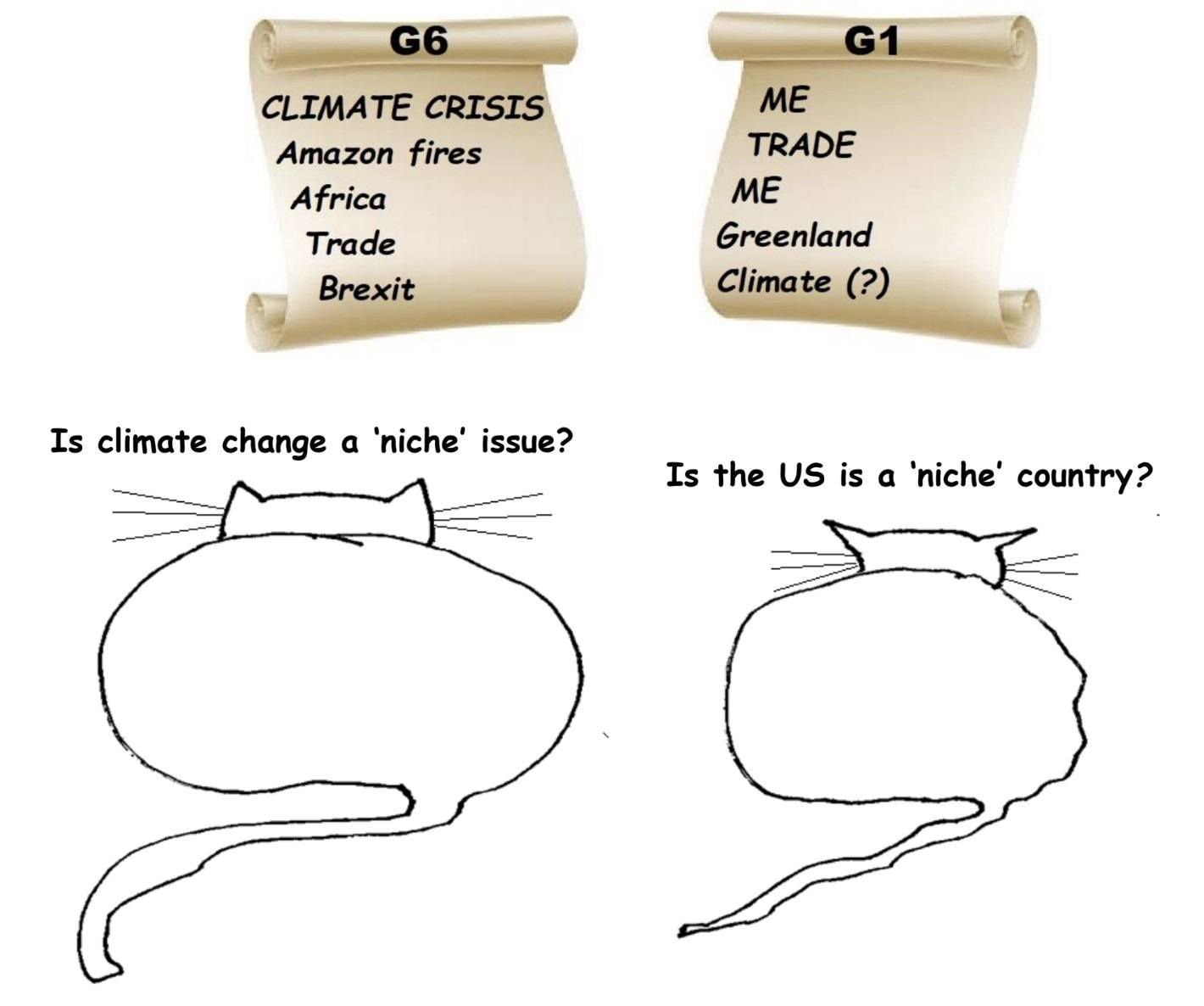

For the most part, I’m content with things, despite my temporal malady. The doctors can’t explain my condition, which they consider untreatable and “psychosomatic” (whatever that means, I’ve forgotten), so there’s nothing I can do but live one week at a time. Most people, apparently, are terrible at thinking about the future. For me, it’s an absolute black hole. It’s difficult because I really do care about the fate of, well, everything: myself, my country, my planet. But I can’t see beyond the week, cursed as I am with a short-sighted brain and countless things-to-do. This is my dilemma. Read more »

Last weekend, a bat got into my house somehow. I first heard it in the small hours of Friday night as it scratched around somewhere near the furnace flue. I didn’t know if it was an animal settling into a new home in my attic, or if perhaps it was going out periodically to get food and bringing it back to feed babies in an established nest. All became clear very late the next night, when the bat managed to get out of the enclosure around the flue and then exit the closet where the furnace is. After some drama that I need not recount here, it flew out the front door, and I stopped gibbering on my front walk and went back inside.

Last weekend, a bat got into my house somehow. I first heard it in the small hours of Friday night as it scratched around somewhere near the furnace flue. I didn’t know if it was an animal settling into a new home in my attic, or if perhaps it was going out periodically to get food and bringing it back to feed babies in an established nest. All became clear very late the next night, when the bat managed to get out of the enclosure around the flue and then exit the closet where the furnace is. After some drama that I need not recount here, it flew out the front door, and I stopped gibbering on my front walk and went back inside. Trapped

Trapped

A recent article by Jane Mayer in The New Yorker, “The Case of Al Franken,”

A recent article by Jane Mayer in The New Yorker, “The Case of Al Franken,”

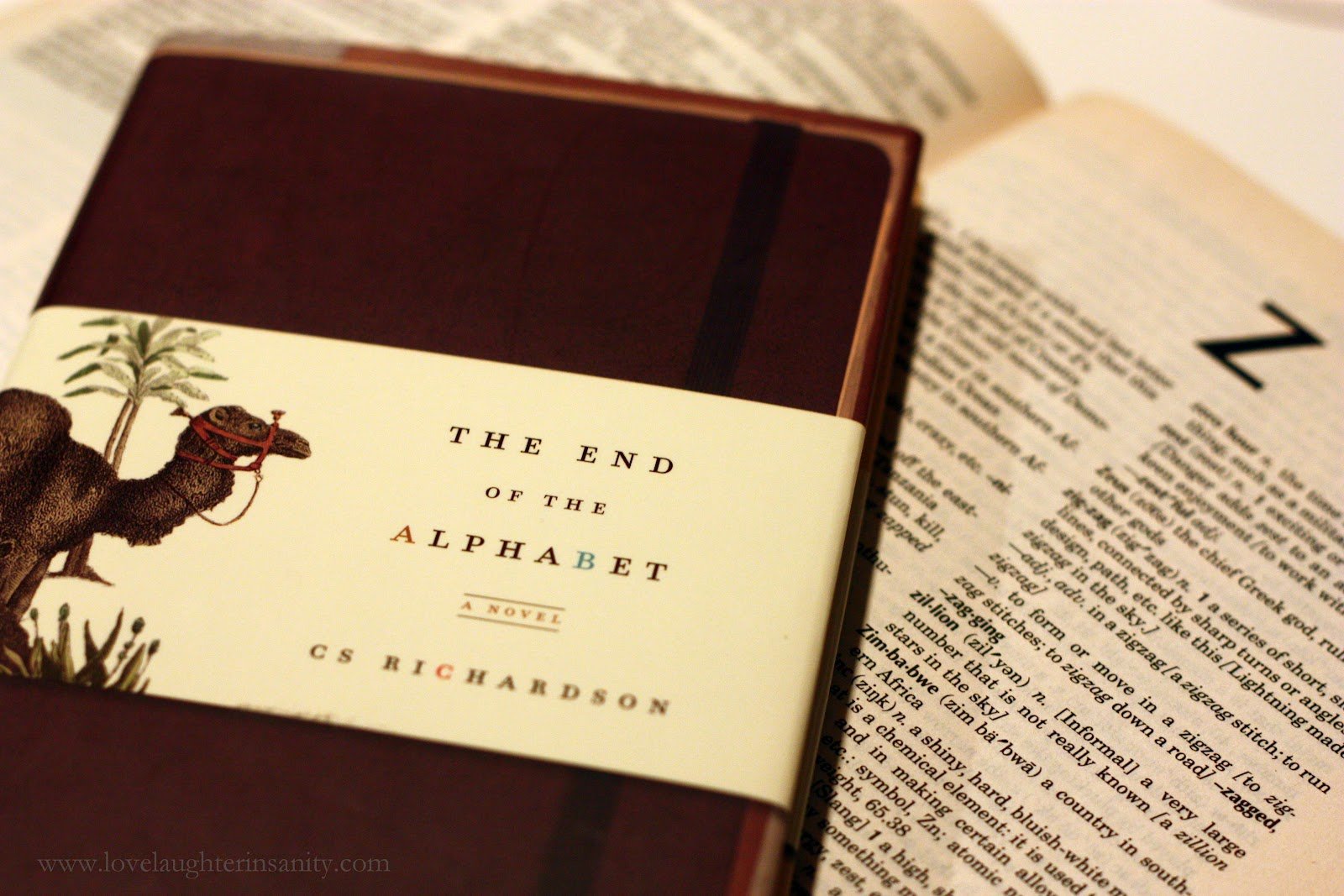

Ambrose finds out he has only weeks to live. How to spend that time is the premise of The End of the Alphabet (2007). It’s a condensed weepie in which Ambrose decides to visit a series of places with his wife that will take them through the alphabet. Somehow Richardson manages to stick to a minimalist elegance which probably saves the book from being schmaltzy book club fodder. And heck, you’d almost look forward to dying the way it’s put. Bucket list: die like this.

Ambrose finds out he has only weeks to live. How to spend that time is the premise of The End of the Alphabet (2007). It’s a condensed weepie in which Ambrose decides to visit a series of places with his wife that will take them through the alphabet. Somehow Richardson manages to stick to a minimalist elegance which probably saves the book from being schmaltzy book club fodder. And heck, you’d almost look forward to dying the way it’s put. Bucket list: die like this.

As a child, author and poet Annie Dillard would traipse through her neighborhood, searching for ideal places to stash pennies where others might find them. In her novel

As a child, author and poet Annie Dillard would traipse through her neighborhood, searching for ideal places to stash pennies where others might find them. In her novel

Why do we value successful art works, symphonies, and good bottles of wine? One answer is that they give us an experience that lesser works or merely useful objects cannot provide—an aesthetic experience. But how does an aesthetic experience differ from an ordinary experience? This is one of the central questions in philosophical aesthetics but one that has resisted a clear answer. Although we are all familiar with paradigm cases of aesthetic experience—being overwhelmed by beauty, music that thrills, waves of delight provoked by dialogue in a play, a wine that inspires awe—attempts to precisely define “aesthetic experience” by showing what all such experiences have in common have been less than successful.

Why do we value successful art works, symphonies, and good bottles of wine? One answer is that they give us an experience that lesser works or merely useful objects cannot provide—an aesthetic experience. But how does an aesthetic experience differ from an ordinary experience? This is one of the central questions in philosophical aesthetics but one that has resisted a clear answer. Although we are all familiar with paradigm cases of aesthetic experience—being overwhelmed by beauty, music that thrills, waves of delight provoked by dialogue in a play, a wine that inspires awe—attempts to precisely define “aesthetic experience” by showing what all such experiences have in common have been less than successful.