by Gabrielle C. Durham

If you grew up in the Western Hemisphere, chances are good that you heard or read several fairytales by the Brothers Grimm as a child. Examples include “Cinderella,” “Rapunzel,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Hansel and Gretel,” and “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” Less well known, and for good reason, are stories of retribution, such as “St. Joseph in the Forest” or “King Thrushbeard,” or gratuitous violence, such as “The Louse and the Flea.”

These German purveyors of macabre moralism were not just busy horrifying children and their parents for countless generations; one of the brothers, Jacob Grimm (1785–1863), was also a linguist, or philologist, as the profession was known in the 19th century. Grimm’s concern was how the branches of the Indo-European languages tree led to the altered Germanic languages. (The original nine Indo-European language families are Indo-European, Armenian, Hellenic, Albanian, Italic/Romance, Balto-Slavic, Celtic, and Germanic, which includes English.)

Specifically, Grimm wanted to explain how consonants changed from Indo-European roots, recognized throughout those languages from Farsi to French, into Germanic languages. We’re going to get a little linguistic here, so bear with me.

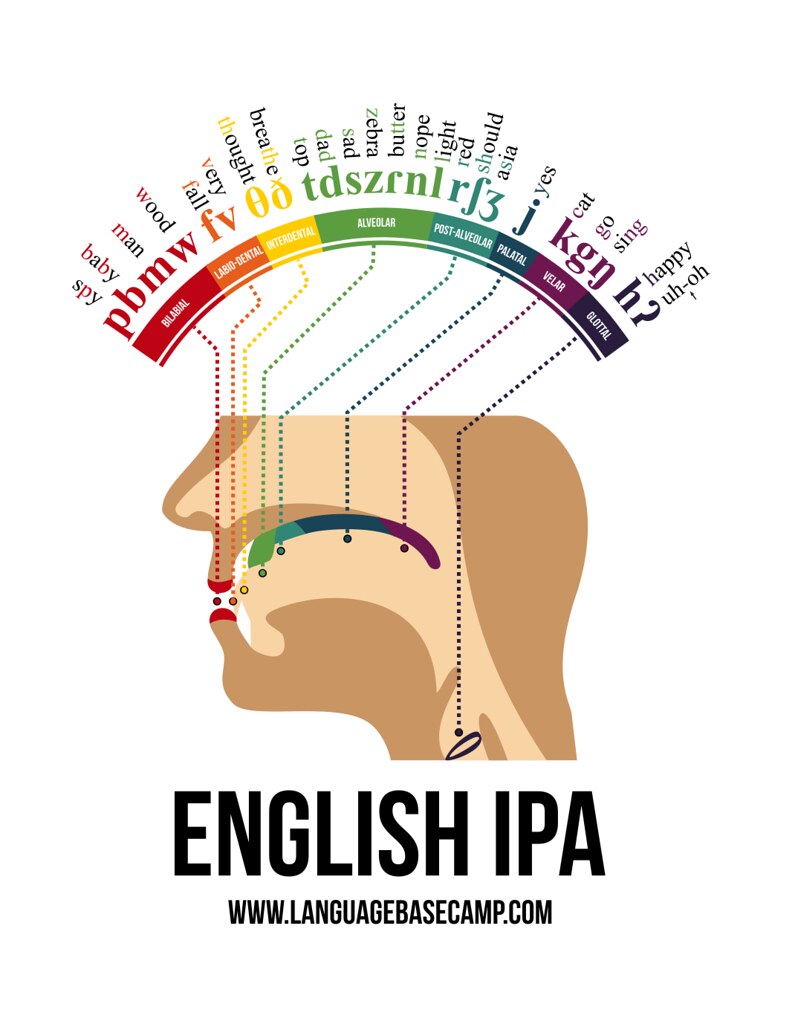

The different sounds we make in every language are named for where they are formed in the mouth.

Photo credit: https://c1.staticflickr.com/1/374/18353951308_2e610bcebe_b.jpg

The sound /p/ is formed with both lips, which is why it is called a bilabial. Other bilabials include /b/, /m/, and /w/. Go ahead and try it. Every time you form these sounds, you will use both lips. When you have a bad cold, more sounds come out as bilabials, because mucus may prevent you from easy access to other parts of your mouth. As sound moves through the mouth, from front to back, the names of the consonants change to fit where they are articulated.

Next up are the labiodental /f/ and /v/ sounds. Then come the interdentals /θ/ and /ð/, and the much more plentiful alveolars, which are formed behind the teeth ridge and include /t/, /d/, /s/, /z/, the tap or flap /ɾ/, /n/, and /l/. The post-alveolars are made behind where the alveolars are produced and include /r/, /ʃ/ and /ʒ/. Next is the palatal /j/, which is actually what we think of as /y/ in International Phonetic Alphabet, which is articulated at the top of your mouth, or your palate. The velars are produced farther back, in the soft palate, toward the back of your mouth, and they are the sounds /k/, /g/, and /ŋ/. Last but not least are the glottals, which are formed with the help of the uvula, which is the hanging part of flesh in the back of your throat you can see in the mirror. There you have it: the sounds your mouth can produce, although depending on the language(s) you speak, you may have the lost the ability as an adult to form some of them without a good amount of work.

So, you got all that, right? According to the law of sound change, or Germanic Sound Shift, that Jacob Grimm devised, when certain sounds are formed in classical languages like Latin and ancient Greek, they do not change where they are formed when articulated in Germanic languages. An /m/ is an /m/ from Latin to German. The shift occurs for certain sounds such as labiodentals turning into labials; and a dental shifts into a linguodental, which is formed with the tongue between the teeth. Sounds that are voiced will become unvoiced, and vice versa going down the linguistic line.

Here are some examples of his law:

Classical languages Germanic languages

Latin pater English father

Greek kard, Latin cord English heart, German Herz

Greek treyis, Latin tres English three

Latin octo German acht

Latin hortus English garden, German Garten

Greek thugater English daughter

Latin fero English bear (to carry)

Latin quod, Sanskrit kad English what

Latin nox, nocti, Greek nuks, nukt English night, German Nacht

The rules do vary based on more technical factors, from which I will spare you. I think you may have suffered enough of an onslaught as is, dear reader.

In his autobiography completed at the end of his life, Jacob Grimm wrote:

“Nearly all my labours have been devoted, either directly or indirectly, to the investigation of our earlier language, poetry, and laws. These studies may have appeared to many, and may still appear, useless; to me they have always seemed a noble and earnest task, definitely and inseparably connected with our common fatherland, and calculated to foster the love of it. My principle has always been in these investigations to under-value nothing, but to utilize the small for the illustration of the great, the popular tradition for the elucidation of the written monuments.”

So, what is the purpose of this law from an amateur linguist who dabbled in law and writing 150 years ago? The law of sound shift helps makes sense of some changes in Indo-European languages, which are spoken and used by 1 in 6 people in the world. When dealing with an oddball like English, it seems practical to use that assistance. Maybe explaining sound change to little ones will mitigate the horror story you just read courtesy of the Brothers Grimm and help them sleep that much more rapidly.