by Joseph Shieber

I want to begin with a parable.

There once was an itinerant salesman by the name of Osip, who made his living selling rags and trinkets in the little villages that lay in the triangle between Smolensk, Minsk and Kiev. He spent his weeks and months traveling between the major cities, finding what he could in one location and selling it on in the next.

One of Osip’s rivals was a man named Mendel, who also plied the same routes selling rags. It was a constant struggle between the two of them to see who could find the better wares, or sell them for a better price.

Now, once, as Osip was traveling on the route from Minsk to Orsha, he happened upon a group of brigands outside of the town of Barysaw. Luckily for Osip, he had spent all of his money in Barysaw, buying new wares, and the brigands were interested in coin, not merchandise, so they let him pass.

When Osip reached Orsha, he encountered Mendel, preparing to make the reverse journey from Orsha to Minsk, and laden with coin to purchase wares along the way, before selling them on.

Now, there are two main routes from Orsha to Minsk. The more direct of the two was the one that Osip had just traveled, passing by the brigands outside of the town of Barysaw. The other is a good bit longer, as one must first head south to Mogilev, before then heading west to Minsk.

As Osip encountered Mendel, then, he faced a quandry. Should he do the right thing, and warn Mendel about the brigands that he would encounter if he took the more direct route? Despite his rivalry with Mendel, Osip was determined to do the right thing.

But now Osip faced a second challenge, of a more practical nature. If he simply warned Mendel, and told him about the brigands, there was little doubt that Mendel would assume that Osip was lying to try to trick him into taking the longer route that went through Mogilev. Osip, however, had an idea.

“Nu, Osip,” said Mendel. “Just arriving from Barysaw? Were the pickings good?”

“No, Mendel,” Osip replied. “I traveled through Mogilev, and as you see I bought up the best stock. I was lucky, too. Just as I departed I saw a gang of brigands setting up to ambush travelers on the road from Mogilev to Orsha. On your travels you should be sure to choose a different route.”

“Ah, Osip,” Mendel cried. “Do you take me for a fool? The route through Barysaw is the faster route from Minsk to Orsha. You must have seen the brigands along that route, or else you heard that the stock in Mogilev is indeed good, and want to get there first yourself by sending me elsewhere. Either way, your plan won’t work. I will take the route to Mogilev.”

And with that, Mendel proceeded to take the route toward Mogilev, on his way to Minsk. As Mendel passed him, Osip smiled to himself, happy that his deceit had saved his rival from a terrible fate.

I wrote the parable myself, but I don’t have any illusions about its originality. In fact, I have the strong feeling that I read a story almost exactly like it, but I was unable to recall where.

The basic message, of course, is that it is possible for someone intentionally to utter a falsehood with the further intention of getting his hearer to believe something true. And though that message has a faint air of paradox, it really shouldn’t be all that surprising. Read more »

Following in the footsteps of the brilliant and exhaustive account of the British opium wars in his hefty Ibis Trilogy, Amitav Ghosh’s latest book Gun Island at just over 300 pages, is a relatively slim volume in which he returns to the Sundarbans to pick up from where his 2004 novel The Hungry Tide left off, with a dire warning about the ravaged ecological plight of the region. Only this time, Ghosh’s novel takes us out of the Sundarbans to Venice via Brooklyn, Kolkata and Los Angeles.

Following in the footsteps of the brilliant and exhaustive account of the British opium wars in his hefty Ibis Trilogy, Amitav Ghosh’s latest book Gun Island at just over 300 pages, is a relatively slim volume in which he returns to the Sundarbans to pick up from where his 2004 novel The Hungry Tide left off, with a dire warning about the ravaged ecological plight of the region. Only this time, Ghosh’s novel takes us out of the Sundarbans to Venice via Brooklyn, Kolkata and Los Angeles. A degree in engineering from India, grad school at an American university, and a job at an American corporation: call it the Indian-engineer version of the American dream. Like hundreds of thousands of Indian immigrants, Ved, the 36-year old protagonist of

A degree in engineering from India, grad school at an American university, and a job at an American corporation: call it the Indian-engineer version of the American dream. Like hundreds of thousands of Indian immigrants, Ved, the 36-year old protagonist of

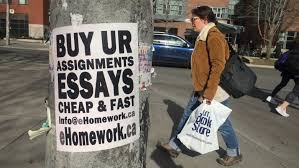

Academic dishonesty is a widespread problem in colleges in many countries, and it is getting worse. One particular form of cheating has become especially common in the age of the internet: students buying custom-written essays–a.k.a. “contract cheating.” A recent study estimated that over 15% of college students had paid someone else to do their work for them;

Academic dishonesty is a widespread problem in colleges in many countries, and it is getting worse. One particular form of cheating has become especially common in the age of the internet: students buying custom-written essays–a.k.a. “contract cheating.” A recent study estimated that over 15% of college students had paid someone else to do their work for them; A while ago findingtimetowrite wrote a

A while ago findingtimetowrite wrote a

It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation.

It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the publication of

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the publication of

An intransigent form of identity politics in combination with neoliberal ideology has left the modern university, if not in ruins, then lacking imagination and cultural capital. It has become a place of sequestered spaces—symbolic and real—where too many students and faculty fear discussing issues deemed to be controversial, inappropriate, or “political.” Across the social sciences/humanities, politics, religion, sex, sexual orientation, climate change, science, gender, economic inequality, poverty, reproductive rights/regulations, homelessness, race, Trump, democracy, capitalism, patriarchy, anti-Semitism, Israel, terrorism, gun violence, sexual violence, and white supremacy are just some of the topics that today make students and even some teachers uncomfortable. At best maybe these topics are addressed by creating some kind of false equivalent in an effort to feign neutrality and keep people comfortable. Discomfort in the classroom from ignorance, tension, power imbalances, conflict, disagreement, or any degree of affective and cognitive dissonance is no longer tolerated. While it used to be considered a fundamental part of the critical learning experience, discomfort of this sort now signals a flaw in pedagogy and/or the curriculum and a betrayal of trust. Learning should always feel good, be nurturing (maternalistic), and, above all, fun. If it’s not then there is hell to pay.

An intransigent form of identity politics in combination with neoliberal ideology has left the modern university, if not in ruins, then lacking imagination and cultural capital. It has become a place of sequestered spaces—symbolic and real—where too many students and faculty fear discussing issues deemed to be controversial, inappropriate, or “political.” Across the social sciences/humanities, politics, religion, sex, sexual orientation, climate change, science, gender, economic inequality, poverty, reproductive rights/regulations, homelessness, race, Trump, democracy, capitalism, patriarchy, anti-Semitism, Israel, terrorism, gun violence, sexual violence, and white supremacy are just some of the topics that today make students and even some teachers uncomfortable. At best maybe these topics are addressed by creating some kind of false equivalent in an effort to feign neutrality and keep people comfortable. Discomfort in the classroom from ignorance, tension, power imbalances, conflict, disagreement, or any degree of affective and cognitive dissonance is no longer tolerated. While it used to be considered a fundamental part of the critical learning experience, discomfort of this sort now signals a flaw in pedagogy and/or the curriculum and a betrayal of trust. Learning should always feel good, be nurturing (maternalistic), and, above all, fun. If it’s not then there is hell to pay.