by Bill Murray

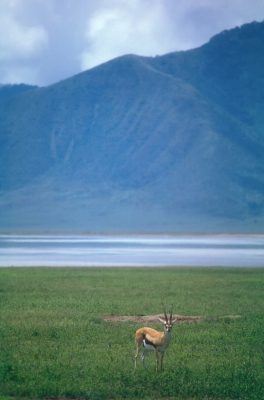

Godfrey points the Land Rover toward Ngorongoro Crater. The road is fine to lull the unwary, but before you know it there is one lane, then no tarmac, then mud and potholes and empty hills.

Godfrey points the Land Rover toward Ngorongoro Crater. The road is fine to lull the unwary, but before you know it there is one lane, then no tarmac, then mud and potholes and empty hills.

Close cropped with a natty little mustache, Godfrey is kempt, forties, paunch-softened, with an easy smile. A veteran guide, he has been here before. Says it will take five hours to do the 250 kilometers to the crater and so it does.

No package tour jets preceded us when we flew into Kilimanjaro International Airport aboard a small plane from Nairobi, so the airport bank wasn’t open. Consequently, we have no Tanzanian Shillings.

Oxen pull plows across the fields. Buses are occasional and private cars are rarer than cows. At the time of this visit (several years ago), the road is primarily for foot traffic, human and animal. No matter how far from a village, people are everywhere walking on the roads, always. They only move to the verge, reluctantly, when a Land Rover thunders by.

The few vehicles you do pass are either chock full of ride-sharing local folks, or they’re hauling two or three white Europeans on safari, or maybe they’re jeeps that read something like, “Africa Wildlife Research Project, funded by Belgian government.”

What do you know, way out here Godfrey knows where to buy a few beers. Two hot Tuskers from Kenya, two hot Safari beers from Tanzania, a roadside bodega, no power, no refrigeration, just a handful of dusty beers on a shelf for four for five dollars at an anonymous shack, friendly enough, opaque to a stranger. Godfrey’s got this round. Read more »

Europeans spent 400 years killing, raping, lying to, and robbing Indigenous Americans. And then, when they’d taken most everything they wanted, they turned Native peoples into tokens, costumes, mascots, and fashion accessories. Like most fashion trends, it’s gone in cycles.

Europeans spent 400 years killing, raping, lying to, and robbing Indigenous Americans. And then, when they’d taken most everything they wanted, they turned Native peoples into tokens, costumes, mascots, and fashion accessories. Like most fashion trends, it’s gone in cycles.

Childrearing practices in the United States underwent a radical alteration during a period from the last decade of the nineteenth century through the first few decades of the twentieth. In 1929, psychologists William Blatz and Helen Bott looked back on the changes they credited to Dr. Luther Emmett Holt, whose childcare manual was first published in 1894 and continued to come out in new editions every few years:

Childrearing practices in the United States underwent a radical alteration during a period from the last decade of the nineteenth century through the first few decades of the twentieth. In 1929, psychologists William Blatz and Helen Bott looked back on the changes they credited to Dr. Luther Emmett Holt, whose childcare manual was first published in 1894 and continued to come out in new editions every few years: I recently read Jill Lepore’s

I recently read Jill Lepore’s  At the heart of French existentialism – and especially the version associated with its most famous representative, Jean Paul Sartre – was the notion of radical freedom. On this view, when we choose, we choose our values and thus what kind of person we are going to be. Nothing can prescribe to us what we ought to value, and the responsibility of freedom is to accept this fact of the human condition without falling into the ‘bad faith’ which would deny it. The moment of existentialism may have passed, but the view that we are radical choosers of our values persists in many quarters, and so I want to consider how well this idea holds up, and what an alternative to it might look like.

At the heart of French existentialism – and especially the version associated with its most famous representative, Jean Paul Sartre – was the notion of radical freedom. On this view, when we choose, we choose our values and thus what kind of person we are going to be. Nothing can prescribe to us what we ought to value, and the responsibility of freedom is to accept this fact of the human condition without falling into the ‘bad faith’ which would deny it. The moment of existentialism may have passed, but the view that we are radical choosers of our values persists in many quarters, and so I want to consider how well this idea holds up, and what an alternative to it might look like. Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Google, often referred to as Big Tech, know more about you than your closest friends and family. They know who you are talking to and what you are talking about, what you are buying or are thinking of buying, how much money you have, and what your fears and desires are. What a few years ago may have sounded like a dystopic vision, is today a reality of our online life (our ‘onlife’). In this setting, even Facebook’s plans of introducing their own currency, Libra, does not seem out of the ordinary.

Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Google, often referred to as Big Tech, know more about you than your closest friends and family. They know who you are talking to and what you are talking about, what you are buying or are thinking of buying, how much money you have, and what your fears and desires are. What a few years ago may have sounded like a dystopic vision, is today a reality of our online life (our ‘onlife’). In this setting, even Facebook’s plans of introducing their own currency, Libra, does not seem out of the ordinary.

A long time ago, on a mountainside in Liechtenstein, I tuned my transistor radio to the Deutschlandfunk, one of neighboring Germany’s state radio stations whose broadcast range leaked into that tiny country. This is what I heard:

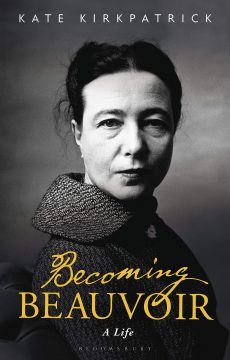

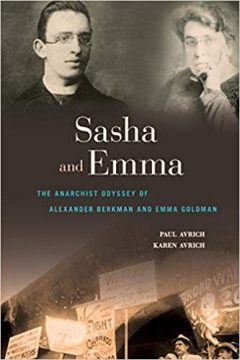

A long time ago, on a mountainside in Liechtenstein, I tuned my transistor radio to the Deutschlandfunk, one of neighboring Germany’s state radio stations whose broadcast range leaked into that tiny country. This is what I heard: Biographies frequently provide us with insights into individual characters in a way that autobiographies might not: the third person narrator offers the prospect of greater ‘objectivity’ when evaluating and narrating information and events and circumstances. And so it is with Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich’s Sasha and Emma: The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman,and Katie Kirkpatrick’s Becoming Beauvoir: A Life.These two books provide a wealth of knowledge on the political and philosophical thinking that engaged the brilliant minds of two significant women of the twentieth century: Emma Goldman and Simone Beauvoir.

Biographies frequently provide us with insights into individual characters in a way that autobiographies might not: the third person narrator offers the prospect of greater ‘objectivity’ when evaluating and narrating information and events and circumstances. And so it is with Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich’s Sasha and Emma: The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman,and Katie Kirkpatrick’s Becoming Beauvoir: A Life.These two books provide a wealth of knowledge on the political and philosophical thinking that engaged the brilliant minds of two significant women of the twentieth century: Emma Goldman and Simone Beauvoir. The life trajectories of the two women could not have been more different: Goldman was a Jewish Russian émigré to the United States; she learned her politics through experience and in that process clarified her political thinking on anarchism, and her life was lived humbly. Beauvoir on the other hand, was from a bourgeois Catholic family and benefited from a formal education and she lived life relatively comfortably. However, despite their divergent lifestyles and politics, similarities can be drawn between their thinking on women, love and freedom.

The life trajectories of the two women could not have been more different: Goldman was a Jewish Russian émigré to the United States; she learned her politics through experience and in that process clarified her political thinking on anarchism, and her life was lived humbly. Beauvoir on the other hand, was from a bourgeois Catholic family and benefited from a formal education and she lived life relatively comfortably. However, despite their divergent lifestyles and politics, similarities can be drawn between their thinking on women, love and freedom.

Suppose you had some undeniable proof of the Everettian or Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics. You would know, then, that there are very many, uncountably many, parallel worlds and that in very many of these there are many, many nearly identical versions of you – as well as many less-closely related “you’s” in still other worlds. Would this change the way you think about yourself and your life? How? Would you take the decisions that you make more or less seriously?

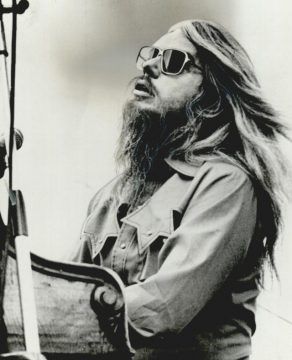

Suppose you had some undeniable proof of the Everettian or Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics. You would know, then, that there are very many, uncountably many, parallel worlds and that in very many of these there are many, many nearly identical versions of you – as well as many less-closely related “you’s” in still other worlds. Would this change the way you think about yourself and your life? How? Would you take the decisions that you make more or less seriously? He released 33 albums and recorded over 400 of songs, earning two Grammys among seven nominations. Yet you probably don’t know who Leon Russell was. For some people he’s a vaguely familiar name they have trouble putting a face or a tune to. Many more have never even heard of him. Because despite his prodigious output, Russell also had a way of being there without letting you know. He was the front man whose real impact came behind the scenes. He was very present, but just out of sight.

He released 33 albums and recorded over 400 of songs, earning two Grammys among seven nominations. Yet you probably don’t know who Leon Russell was. For some people he’s a vaguely familiar name they have trouble putting a face or a tune to. Many more have never even heard of him. Because despite his prodigious output, Russell also had a way of being there without letting you know. He was the front man whose real impact came behind the scenes. He was very present, but just out of sight.