by Charlie Huenemann

The “Consequence Argument” is a powerful argument for the conclusion that, if determinism is true, then we have no control over what we do or will do. The argument is straightforward and simple (as given in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy):

The “Consequence Argument” is a powerful argument for the conclusion that, if determinism is true, then we have no control over what we do or will do. The argument is straightforward and simple (as given in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy):

Premise 1: No one has power over the facts of the past and the laws of nature.

Premise 2: No one has power over the fact that the facts of the past and the laws of nature entail every fact of the future (i.e., determinism is true).

Conclusion: Therefore, no one has power over the facts of the future.

Premise 1 seems awfully secure. Authors of history books might change people’s beliefs about the past, but try as they might, they won’t actually change the past. Similarly, scientists may write about the laws of nature however they please, but nothing they write will change those laws. No one can control the facts of the past, or the laws of nature.

Premise 2 looks pretty good too. For at least great big patches of nature, events happen because of the way things are or have been, and because of the continuous governance of the laws of nature. True, there are subatomic phenomena that seem to be indeterministic (Einstein was wrong, and God or nature does seem to roll teensy-weensy dice). But for whatever reason, it also seems that as these subatomic bits are assembled into larger parts of nature, the dice rolling seems to no longer have any effect, and at that point we enter upon a deterministic universe. Certainly by the time we get to big globs of neurons within the skulls of homo sapiens, wired up to eyeballs and limbs, we are in a domain where the fact is that the facts of the past and the laws of nature entail every fact of the future.

And the conclusion follows: we have no power to affect the future. So that’s it. We’re done. Read more »

What can I make of these decisions emerging out of the blue, which I appear to act upon “freely?” What are the consequences of how I choose to react to them? Although these are vague philosophical musings, let’s look instead at the science of it all. I’m a layman, neither scientist nor philosopher, but as we are rediscovering, scientists are a less fuzzy lot than philosophers. I’m more likely to ask the woman with the medical degree about the true meaning of my dry cough than to ask philosopher

What can I make of these decisions emerging out of the blue, which I appear to act upon “freely?” What are the consequences of how I choose to react to them? Although these are vague philosophical musings, let’s look instead at the science of it all. I’m a layman, neither scientist nor philosopher, but as we are rediscovering, scientists are a less fuzzy lot than philosophers. I’m more likely to ask the woman with the medical degree about the true meaning of my dry cough than to ask philosopher

For the same reason as large parts of the world, I spend even more time indoors these days than I already would. One thing I have been doing is rereading the Harry Potter books – or paying Stephen Fry to read them to me.

For the same reason as large parts of the world, I spend even more time indoors these days than I already would. One thing I have been doing is rereading the Harry Potter books – or paying Stephen Fry to read them to me.

In the memoir, Running Toward Mystery: The Adventure of an Unconventional Life, the Venerable Tenzin Priyadarshi chooses to become a monk at the peak of his youthful potential. He rejects the spiritual path as a mere life enhancer and encourages readers to embark on a more totalizing journey of self-actualization. By embracing mystery, as opposed to cultural explanations, we can arrive at deeper questions. This wish bookends this carefully written memoir, which is co-authored by Zara Houshmand. Despite an already crowded landscape of books depicting religious quests and spiritual advice- both classics and new works – this book is bound to be widely read if for no other reason than Priyadarshi’s current role as a thought leader while serving as the first Buddhist chaplain at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

In the memoir, Running Toward Mystery: The Adventure of an Unconventional Life, the Venerable Tenzin Priyadarshi chooses to become a monk at the peak of his youthful potential. He rejects the spiritual path as a mere life enhancer and encourages readers to embark on a more totalizing journey of self-actualization. By embracing mystery, as opposed to cultural explanations, we can arrive at deeper questions. This wish bookends this carefully written memoir, which is co-authored by Zara Houshmand. Despite an already crowded landscape of books depicting religious quests and spiritual advice- both classics and new works – this book is bound to be widely read if for no other reason than Priyadarshi’s current role as a thought leader while serving as the first Buddhist chaplain at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

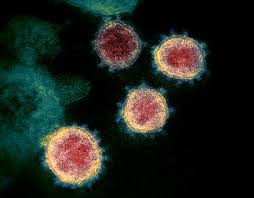

Among other things Covid-19 is a moral crisis. It requires suspending the usual rules about who deserves what, firstly because it is impossible for many of us to pay what we owe in these conditions, and secondly because of the priority of the humanitarian duty to save as many lives as possible. Nevertheless we must not forget about justice. In particular we must make sure that the costs of this crisis are not born disproportionately by the poor, those least able to afford the burden but also least able to escape it.

Among other things Covid-19 is a moral crisis. It requires suspending the usual rules about who deserves what, firstly because it is impossible for many of us to pay what we owe in these conditions, and secondly because of the priority of the humanitarian duty to save as many lives as possible. Nevertheless we must not forget about justice. In particular we must make sure that the costs of this crisis are not born disproportionately by the poor, those least able to afford the burden but also least able to escape it.

The current Covid 19 pandemic is undoubtedly a disaster for millions of people: for those who die, who grieve for the dead, who suffer through a traumatic illness, or who, suddenly lacking work and income, face the prospect of dire poverty as the inevitable recession kicks in. And there are other bad consequences that one might not describe as ‘disastrous” but which are certainly significant: the stress experienced by all those providing care for the sick; the interruption in the education of students; the strain put on families holed up together perhaps for months on end; the loneliness suffered by those who are truly isolated; and the blighted career prospects of new graduates in both the public and the private sectors.

The current Covid 19 pandemic is undoubtedly a disaster for millions of people: for those who die, who grieve for the dead, who suffer through a traumatic illness, or who, suddenly lacking work and income, face the prospect of dire poverty as the inevitable recession kicks in. And there are other bad consequences that one might not describe as ‘disastrous” but which are certainly significant: the stress experienced by all those providing care for the sick; the interruption in the education of students; the strain put on families holed up together perhaps for months on end; the loneliness suffered by those who are truly isolated; and the blighted career prospects of new graduates in both the public and the private sectors.

The coronavirus amounts to an ongoing, real-world experiment in societal response to an international calamity. The pandemic will be studied for decades, but COVID has already taught us much about the relationship between science and decision-making.

The coronavirus amounts to an ongoing, real-world experiment in societal response to an international calamity. The pandemic will be studied for decades, but COVID has already taught us much about the relationship between science and decision-making. “Will we survive this?” my husband asks me as we lounge around the living room, glued to our laptops. “We are in the vulnerable group.” I look up at a bald man with thinning gray tufts over his ears, peering anxiously at me over black-rimmed glasses. Yes, we are certainly in the vulnerable group. What happened to that bright-eyed young man with fifteen pounds of black hair on his head, the one sporting sideburns that put Elvis to shame? Over his shoulder I see our son also looking expectantly at me, Camus’s The Plague in hand, open halfway.

“Will we survive this?” my husband asks me as we lounge around the living room, glued to our laptops. “We are in the vulnerable group.” I look up at a bald man with thinning gray tufts over his ears, peering anxiously at me over black-rimmed glasses. Yes, we are certainly in the vulnerable group. What happened to that bright-eyed young man with fifteen pounds of black hair on his head, the one sporting sideburns that put Elvis to shame? Over his shoulder I see our son also looking expectantly at me, Camus’s The Plague in hand, open halfway.