by Maniza Naqvi

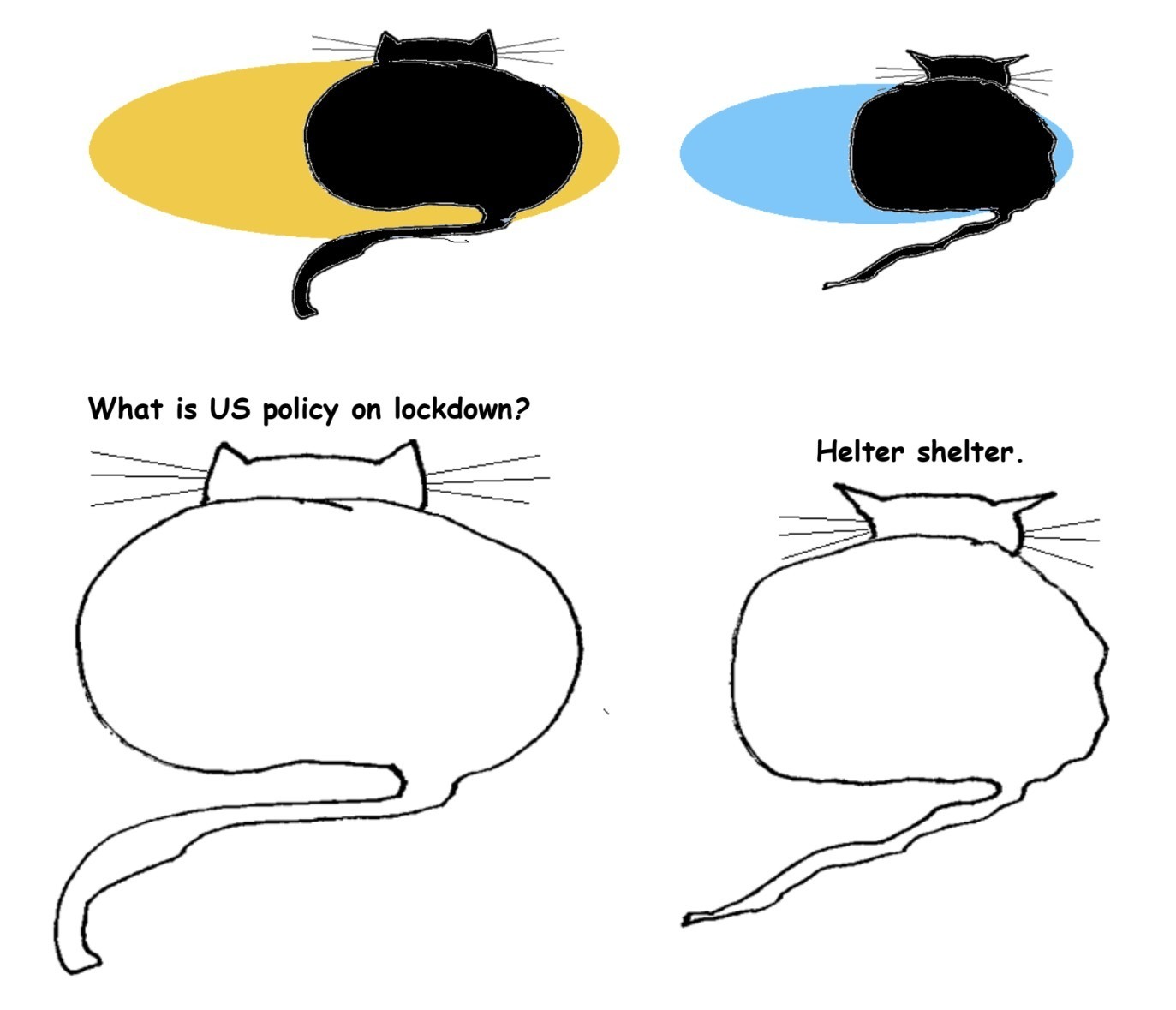

Today will mark the death of at least one hundred thousand Americans because of COVID. The science was clear. Lockdown. Stop movement. Distance. This would have stopped large numbers of people dying. In short, stopping the virus from becoming a pandemic meant pausing the profit principle.

Today will mark the death of at least one hundred thousand Americans because of COVID. The science was clear. Lockdown. Stop movement. Distance. This would have stopped large numbers of people dying. In short, stopping the virus from becoming a pandemic meant pausing the profit principle.

The pandemic has laid bare the cruel and clear fact that pausing for people is not possible for capitalism. If the accumulation of capital is the primary principle, then humans in comparison to this hegemon are only inputs for its expansion and its accumulation—humans are interchangeable and dispensable while the hegemon of capitalism is supreme. And all else are in the service of ‘his’ malady.

Those who should have acted and acted fast and done everything they could, did not. Even though they knew what the science was saying early on. All of them. Their Intelligence services were surely telling them what was going on in China? Or were they only focused on maximizing the sales of weapons? A war on Iran? If the Intelligence Services knew then why did lockdowns not happen earlier? Read more »

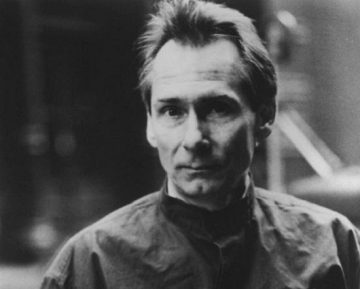

Jon Hassell is one of America’s musical treasures, and I’ve been listening to his music for forty years, so when I heard he needed help for his medical care, I decided to make a mix of his music. This mix actually grew into two mixes, so look for another one next month. This one features Jon playing with other musicians, and part two will feature other musicians whom Jon has influenced (and a bit more from Jon himself).

Jon Hassell is one of America’s musical treasures, and I’ve been listening to his music for forty years, so when I heard he needed help for his medical care, I decided to make a mix of his music. This mix actually grew into two mixes, so look for another one next month. This one features Jon playing with other musicians, and part two will feature other musicians whom Jon has influenced (and a bit more from Jon himself).

Something has happened in the last forty days. The planet has gone quiet, a vast, reverberating, gesticulating global chorus suddenly muted by something wee and invisible which is borne across continents, streets and rooms by friends and strangers. Mass extinction, once the whispered woe of a distant future, suddenly sounds louder and doable in the here and now. The world is compelled to gaze at its own mortality.

Something has happened in the last forty days. The planet has gone quiet, a vast, reverberating, gesticulating global chorus suddenly muted by something wee and invisible which is borne across continents, streets and rooms by friends and strangers. Mass extinction, once the whispered woe of a distant future, suddenly sounds louder and doable in the here and now. The world is compelled to gaze at its own mortality. The month of Ramadan is at once a time of respite from the external— when one’s focus shifts from worldly affairs to the spiritual— and a time to deepen one’s sense of compassion and fellow-feeling via the rigors of daily fasting, prayer, reflection and generous giving. It is a time to break free from day to day concerns and to pay attention to one’s lifelong inner journey, whether it is through revitalizing the connection with the Divine or investing in human relations: personal, communal, and global.

The month of Ramadan is at once a time of respite from the external— when one’s focus shifts from worldly affairs to the spiritual— and a time to deepen one’s sense of compassion and fellow-feeling via the rigors of daily fasting, prayer, reflection and generous giving. It is a time to break free from day to day concerns and to pay attention to one’s lifelong inner journey, whether it is through revitalizing the connection with the Divine or investing in human relations: personal, communal, and global.

The COVID-19 pandemic has instigated talk of the systemic- or societal relevance of institutions and professions. Quickly, attributions of systemic relevance have become a matter of distribution of resources. In Germany, for example,

The COVID-19 pandemic has instigated talk of the systemic- or societal relevance of institutions and professions. Quickly, attributions of systemic relevance have become a matter of distribution of resources. In Germany, for example,  What is worse – coronavirus itself, or the social and economic catastrophe that comes with it?

What is worse – coronavirus itself, or the social and economic catastrophe that comes with it? Like most people who have time to think in these stressful days, I have been thinking about life after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed – mostly at a personal level, but also a little about the world at large. This essay is an attempt to put some of these thoughts down as a time-capsule of how things appear from this perch in May of 2020, the first year of the New Plague.

Like most people who have time to think in these stressful days, I have been thinking about life after the COVID-19 pandemic has passed – mostly at a personal level, but also a little about the world at large. This essay is an attempt to put some of these thoughts down as a time-capsule of how things appear from this perch in May of 2020, the first year of the New Plague. What’s the universe made up of? Most people who have read popular science would probably say “Mostly hydrogen, along with some helium.” Even people with a passing interest in science usually know that the sun and stars are powered by nuclear reactions involving the conversion of hydrogen to helium. The dominance of hydrogen in the universe is so important that in the 1960s, two physicists suggested that the best way to communicate with alien civilizations would be to broadcast radio waves at the frequency of hydrogen atoms. Today the discovery that the stars, galaxies and the great beyond are primarily made up of hydrogen stands as one of the most important discoveries in our quest for the origin of the universe. What a lot of people don’t know is that this critical fact was discovered by a woman who should have won a Nobel Prize for it, who went against all conventional wisdom questioning her discovery and who was often held back because of her gender and maverick nature. And yet, in spite of these drawbacks, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin achieved so many firsts: the first PhD thesis in astronomy at Harvard and one that is regarded as among the most important in science, the first woman to become a professor at Harvard and the first woman to chair a major department at the university.

What’s the universe made up of? Most people who have read popular science would probably say “Mostly hydrogen, along with some helium.” Even people with a passing interest in science usually know that the sun and stars are powered by nuclear reactions involving the conversion of hydrogen to helium. The dominance of hydrogen in the universe is so important that in the 1960s, two physicists suggested that the best way to communicate with alien civilizations would be to broadcast radio waves at the frequency of hydrogen atoms. Today the discovery that the stars, galaxies and the great beyond are primarily made up of hydrogen stands as one of the most important discoveries in our quest for the origin of the universe. What a lot of people don’t know is that this critical fact was discovered by a woman who should have won a Nobel Prize for it, who went against all conventional wisdom questioning her discovery and who was often held back because of her gender and maverick nature. And yet, in spite of these drawbacks, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin achieved so many firsts: the first PhD thesis in astronomy at Harvard and one that is regarded as among the most important in science, the first woman to become a professor at Harvard and the first woman to chair a major department at the university.

I sometimes consider becoming a skeptic, but then I’m not so sure what that entails.

I sometimes consider becoming a skeptic, but then I’m not so sure what that entails.