by Ram Manikkalingam

It was December 1999. Two years before the attacks on the Twin Towers by Al Qaeda. I landed at Geneva airport and checked into my hotel. I was on my way to Colombo. I had stopped in Geneva to meet David Petrasek. I had never met him before. But I knew that he was working on a project on the human rights violations of armed groups. Human rights activists in Sri Lanka were struggling with the violations of the Tamil Tigers. The Tigers controlled territory and ran a de facto state in the North. While people on the ground in these areas were dealing with the oppressive rule of the Tigers through small scale resistance or highlighting their violations, there was no coherent international framework in human rights to confront the violations of armed groups, other than the laws of war. But these dealt with fighting and its impact on civilians and soldiers, not with the behaviour of non-state armed groups in other situations.

States were wary of conceding that these groups controlled territory and managed quasi-governmental functions. Doing so would be an admission of weakness on their part. An admission that they did not control all of their sovereign territory. And many international human rights organisations, not to mention legal instruments laid primary, if not sole responsibility, for violations on the state. This was a legacy of the struggle against one party dictatorships in Eastern Europe and military dictatorships Latin America. But this was a far cry from reality. The lived experience of people in large swathes of Latin America, Asia and Africa was different. Many armed groups were not necessarily seen as freedom fighters struggling against oppression, but often as oppressive violators of human rights, themselves.

At that time, I was working at the Rockefeller Foundation in New York. I was looking for innovative and interesting initiatives that connected local challenges to international efforts in the area of peace, security and human rights. I heard about David’s initiative and decided to meet with him on my way home to Colombo. David looked at the silences in human rights work – what were policy makers, human rights activists and scholars not talking about – either because of political bias, academic fashion or political correctness. David could not have predicted that two years later, on September 11th, 2001, the issue of armed groups, their funding, and their actions, not to mention, their impact on world politics literally exploded on the international security and human rights scene. But David was already prepared as a thinker and an activist. Read more »

There is a statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park. It is tucked in at the intersection of West and Bethesda Drives, massive and unmoving, implacable and forbidding. Despite its size, it goes largely unnoticed, except as a meeting point.

There is a statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park. It is tucked in at the intersection of West and Bethesda Drives, massive and unmoving, implacable and forbidding. Despite its size, it goes largely unnoticed, except as a meeting point. I’ve taught shittily these last two months. That’s nothing a teacher ever wants to admit and normally has no excuse for, but these are not normal times.

I’ve taught shittily these last two months. That’s nothing a teacher ever wants to admit and normally has no excuse for, but these are not normal times.

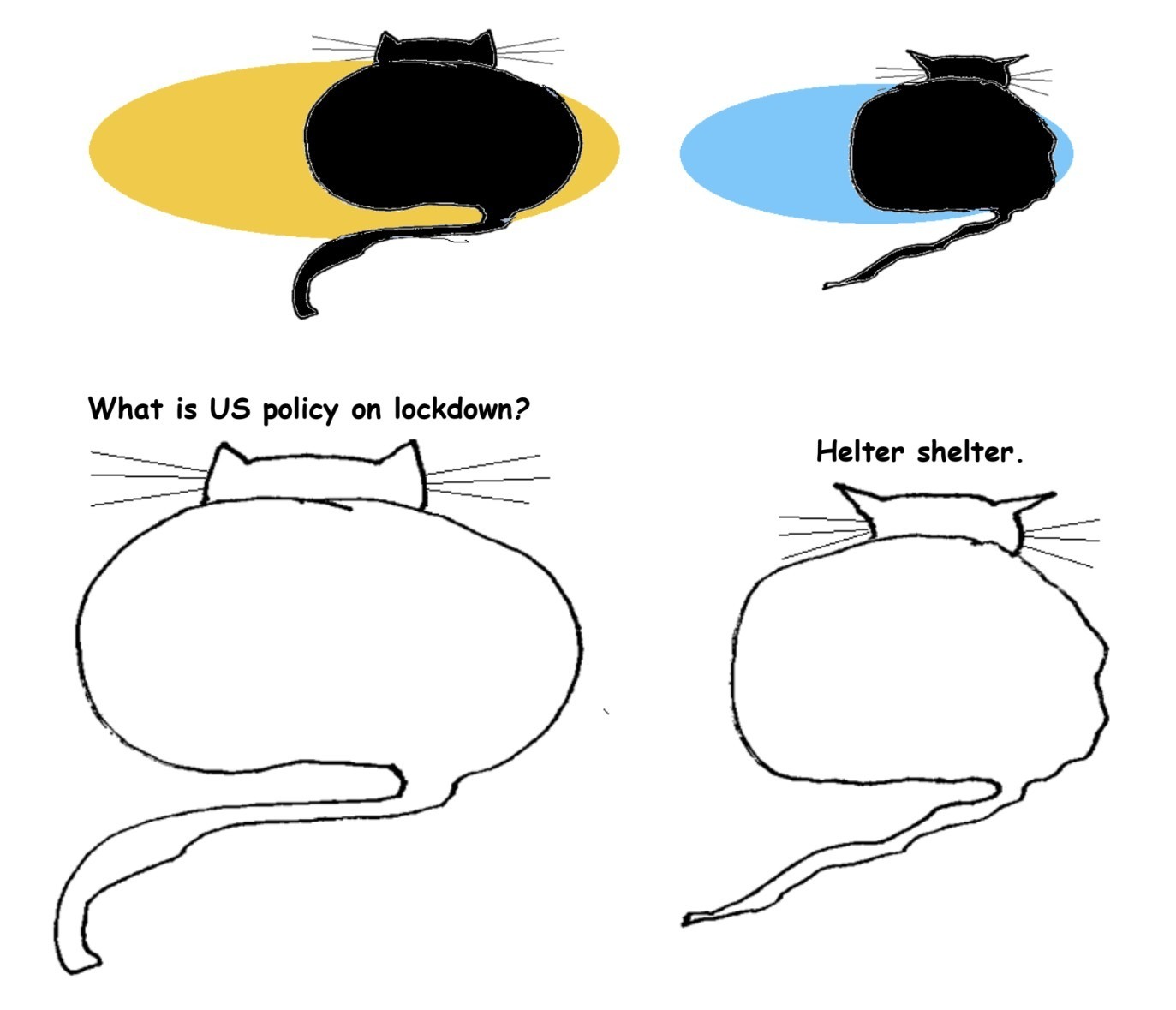

Two months ago, COVID lockdown was still new; in the US it was horrific that

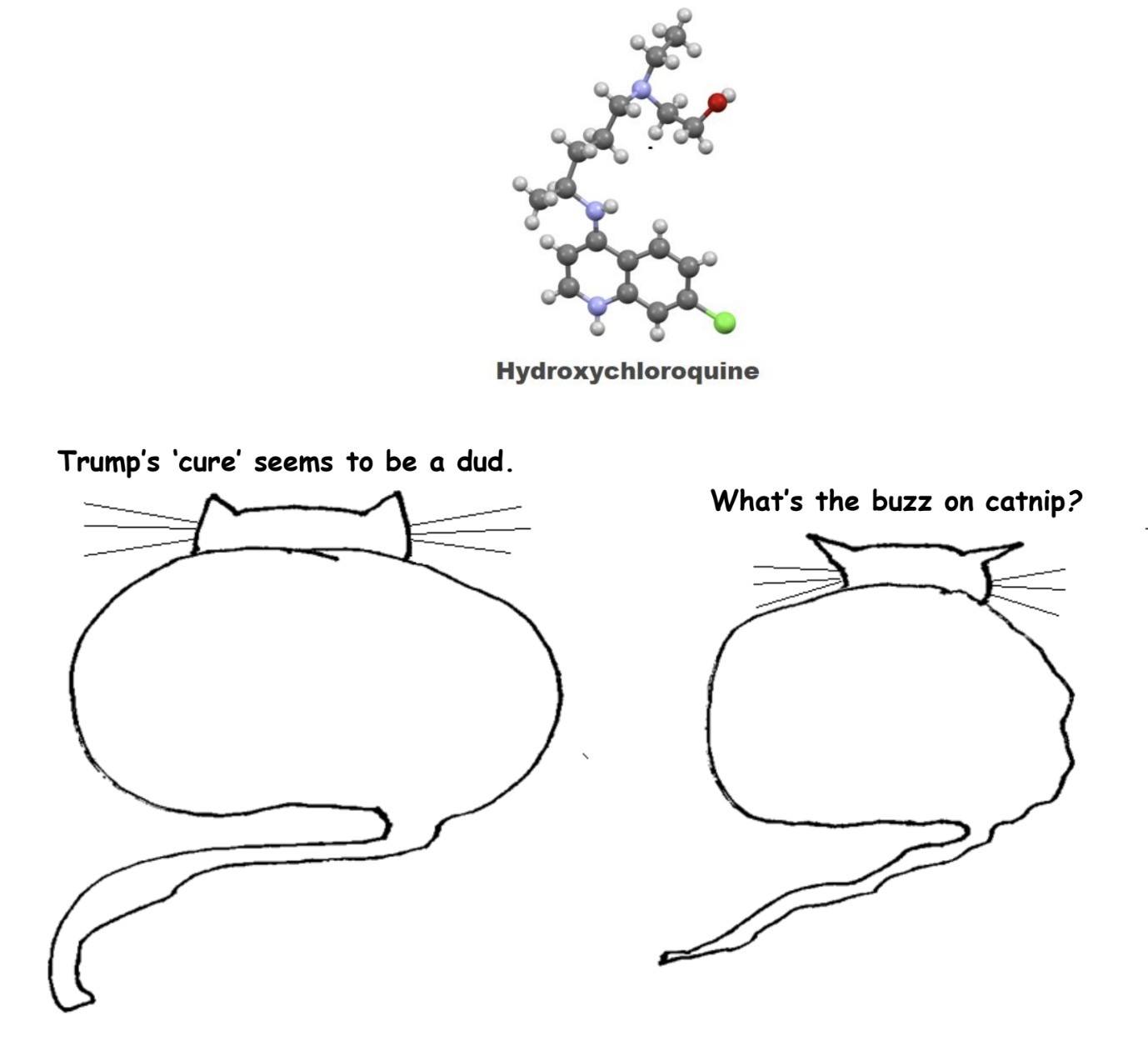

Two months ago, COVID lockdown was still new; in the US it was horrific that  Today will mark the death of at least one hundred thousand Americans because of COVID. The science was clear. Lockdown. Stop movement. Distance. This would have stopped large numbers of people dying. In short, stopping the virus from becoming a pandemic meant pausing the profit principle.

Today will mark the death of at least one hundred thousand Americans because of COVID. The science was clear. Lockdown. Stop movement. Distance. This would have stopped large numbers of people dying. In short, stopping the virus from becoming a pandemic meant pausing the profit principle.

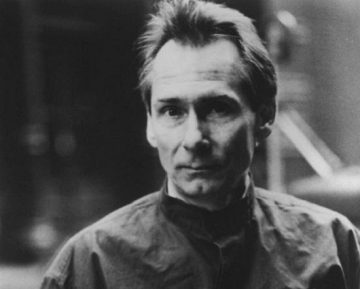

Jon Hassell is one of America’s musical treasures, and I’ve been listening to his music for forty years, so when I heard he needed help for his medical care, I decided to make a mix of his music. This mix actually grew into two mixes, so look for another one next month. This one features Jon playing with other musicians, and part two will feature other musicians whom Jon has influenced (and a bit more from Jon himself).

Jon Hassell is one of America’s musical treasures, and I’ve been listening to his music for forty years, so when I heard he needed help for his medical care, I decided to make a mix of his music. This mix actually grew into two mixes, so look for another one next month. This one features Jon playing with other musicians, and part two will feature other musicians whom Jon has influenced (and a bit more from Jon himself).