by Eric J. Weiner

In the wake of the pandemic, many people sense an opportunity to reimagine and rewrite public education so that it aligns with their particular political agendas. Progressives sense an opportunity to reassert the critical capacities of a democratic education. From the religious right, there is an attempt to blur the lines between secular and religious goals and needs. Neoliberals sense an opportunity to further privatize public education and align learning to the needs of capital. Democratic socialists sense an opportunity to recreate a system that can equitably distribute opportunity across race, class and gender. Technologists see the potential to create a techno-utopia of learning that is no longer constrained by terrestrial notions of time and space. Neoconservatives want to reclaim public education as the engine of white nationalism and free-market capitalism through the curricular standardization of “core” knowledge. What they all can agree on is the essential political nature of public education; it has always been a mirror that reflects the best and worst impulses of our nation. If you want to get a sense of a nation’s health, just look at its public education system. From the good and the bad to the downright ugly, our schools have always represented who we have been, who we are, and who we hope to be.

As the pandemic continues to rip back the curtain on economic and political inequality in the United States, it also has highlighted the nation’s failure to provide meaningful and equitable educational opportunities to all of our school-age children. With this in mind, I’ve provided a very brief and admittedly incomplete blueprint that might help at a foundational level guide all of those people–some more qualified than others–who are now sensing an opportunity to reimagine public education. Read more »

There is a statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park. It is tucked in at the intersection of West and Bethesda Drives, massive and unmoving, implacable and forbidding. Despite its size, it goes largely unnoticed, except as a meeting point.

There is a statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park. It is tucked in at the intersection of West and Bethesda Drives, massive and unmoving, implacable and forbidding. Despite its size, it goes largely unnoticed, except as a meeting point. I’ve taught shittily these last two months. That’s nothing a teacher ever wants to admit and normally has no excuse for, but these are not normal times.

I’ve taught shittily these last two months. That’s nothing a teacher ever wants to admit and normally has no excuse for, but these are not normal times.

Two months ago, COVID lockdown was still new; in the US it was horrific that

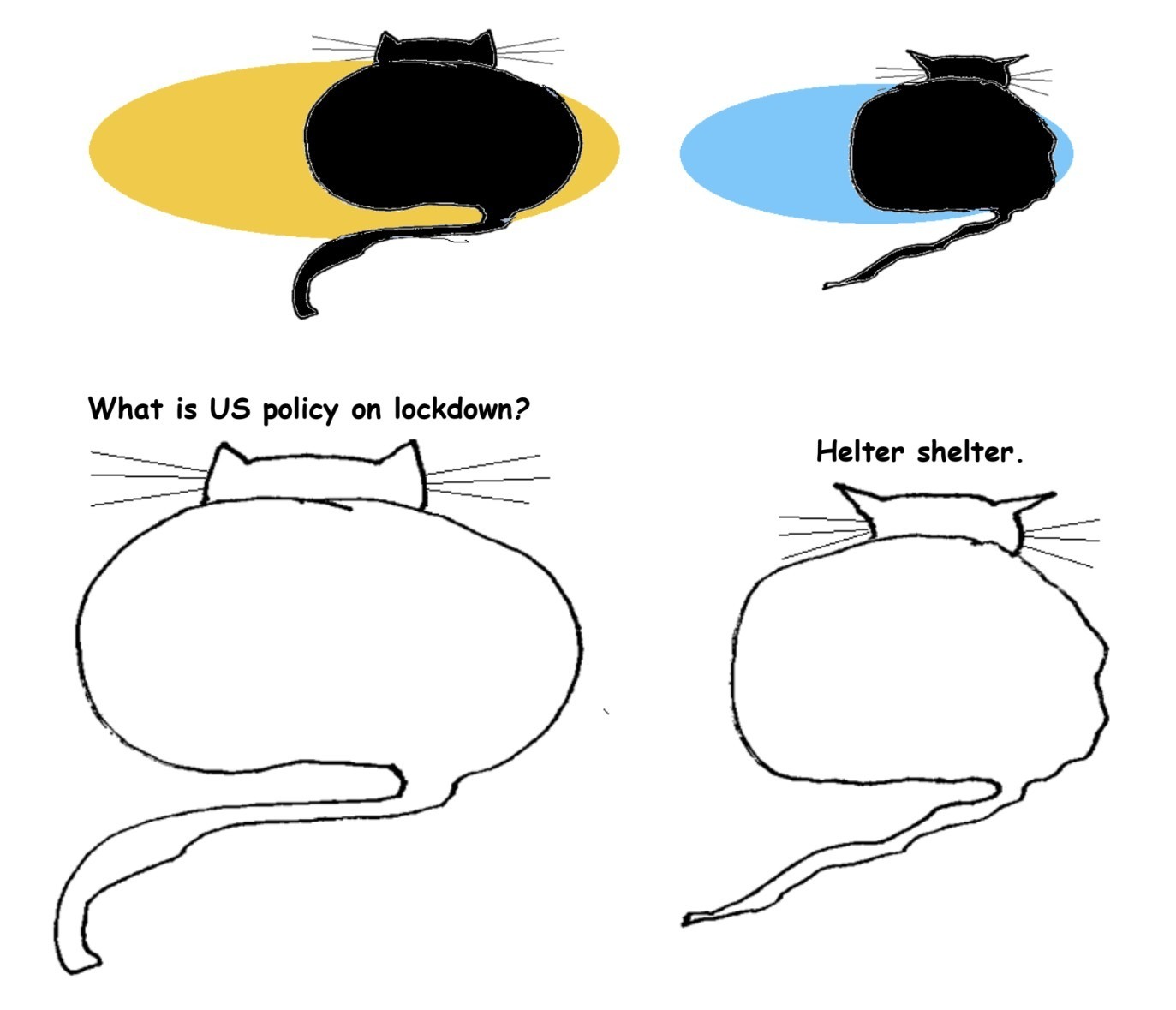

Two months ago, COVID lockdown was still new; in the US it was horrific that  Today will mark the death of at least one hundred thousand Americans because of COVID. The science was clear. Lockdown. Stop movement. Distance. This would have stopped large numbers of people dying. In short, stopping the virus from becoming a pandemic meant pausing the profit principle.

Today will mark the death of at least one hundred thousand Americans because of COVID. The science was clear. Lockdown. Stop movement. Distance. This would have stopped large numbers of people dying. In short, stopping the virus from becoming a pandemic meant pausing the profit principle.

Jon Hassell is one of America’s musical treasures, and I’ve been listening to his music for forty years, so when I heard he needed help for his medical care, I decided to make a mix of his music. This mix actually grew into two mixes, so look for another one next month. This one features Jon playing with other musicians, and part two will feature other musicians whom Jon has influenced (and a bit more from Jon himself).

Jon Hassell is one of America’s musical treasures, and I’ve been listening to his music for forty years, so when I heard he needed help for his medical care, I decided to make a mix of his music. This mix actually grew into two mixes, so look for another one next month. This one features Jon playing with other musicians, and part two will feature other musicians whom Jon has influenced (and a bit more from Jon himself).

Something has happened in the last forty days. The planet has gone quiet, a vast, reverberating, gesticulating global chorus suddenly muted by something wee and invisible which is borne across continents, streets and rooms by friends and strangers. Mass extinction, once the whispered woe of a distant future, suddenly sounds louder and doable in the here and now. The world is compelled to gaze at its own mortality.

Something has happened in the last forty days. The planet has gone quiet, a vast, reverberating, gesticulating global chorus suddenly muted by something wee and invisible which is borne across continents, streets and rooms by friends and strangers. Mass extinction, once the whispered woe of a distant future, suddenly sounds louder and doable in the here and now. The world is compelled to gaze at its own mortality.