by Joshua Wilbur

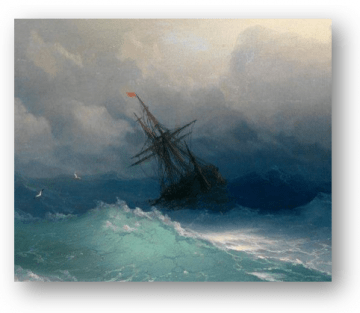

There are times when I can’t look away from The Avenue at Middelharnis.

Completed in 1689 by the Dutch Golden Age artist Meindert Hobbema, the painting has entranced viewers for centuries. The English landscapists of the Romantic period admired and emulated its unusual composition. A young Van Gogh saw The Avenue in London’s National Gallery in 1884. “Look out for the Hobbema,” he would later write in a letter to his brother Theo. René Magritte allegedly produced forgeries of Hobbema’s paintings, and his Empire of Light seems to me a surreal reinterpretation of the Dutch master’s masterwork.

I say that I can’t look away from the painting because I set it as my computer’s background a few months ago. Artsy, I know. I see The Avenue a few times a day, usually in browser-obscured flashes. Sometimes I’ll push everything aside and just space out into it.

The painting is a great example of an “open” work of art. As described by Umberto Eco, open works encourage multiple interpretations and respond to the viewer’s evershifting historical situation, stage in life, or mood. If closed creations communicate one thing, open works communicate many things. They meet us where we are. I should say something about where I am and where we are before going further down The Avenue. Read more »

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose.

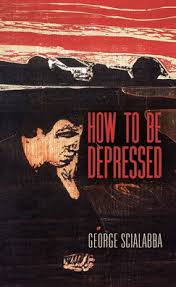

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose. Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

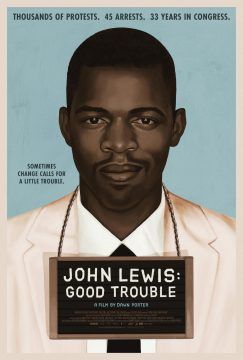

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

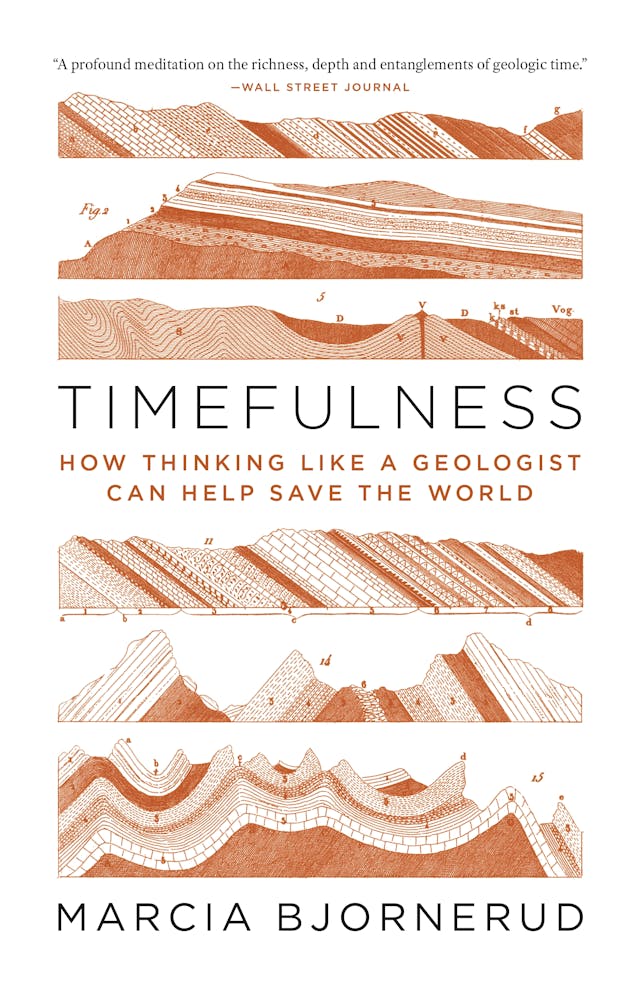

by Paul Braterman

by Paul Braterman

John Lewis: Good Trouble

John Lewis: Good Trouble

The coronavirus pandemic has massively disrupted the working lives of millions of people. For those who have lost their jobs, income, or work-related benefits, this can mean serious hardship and anxiety. For others, it has meant getting used to new routines and methods of working. For all of us, though, it should prompt reflection on how we think about work in general–both as a curse and as a blessing. Here, I want to focus on how work relates to time.

The coronavirus pandemic has massively disrupted the working lives of millions of people. For those who have lost their jobs, income, or work-related benefits, this can mean serious hardship and anxiety. For others, it has meant getting used to new routines and methods of working. For all of us, though, it should prompt reflection on how we think about work in general–both as a curse and as a blessing. Here, I want to focus on how work relates to time. Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up.

Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up. In a survey released at the end of May by the AP and the NORC Center for public affairs research, 49% of Americans said they intended to be vaccinated against the new coronavirus, 31% said they were unsure, and 20% said they would not get the vaccine.

In a survey released at the end of May by the AP and the NORC Center for public affairs research, 49% of Americans said they intended to be vaccinated against the new coronavirus, 31% said they were unsure, and 20% said they would not get the vaccine.