by Charlie Huenemann

By 2025, protective living communities (PLCs) had started to form. The earliest PLCs, such as New Promise and New New Babylon, based themselves on rationalist doctrines: decisions informed by best available science, and either utilitarian ethics or Rawlsian principles of justice (principally, respect for individual autonomy and a concern to improve the lives of those most disadvantaged). Membership in these communities was exclusive and tightly guarded, and they had the advantage of the relatively higher levels of wealth controlled by their members.

By 2025, protective living communities (PLCs) had started to form. The earliest PLCs, such as New Promise and New New Babylon, based themselves on rationalist doctrines: decisions informed by best available science, and either utilitarian ethics or Rawlsian principles of justice (principally, respect for individual autonomy and a concern to improve the lives of those most disadvantaged). Membership in these communities was exclusive and tightly guarded, and they had the advantage of the relatively higher levels of wealth controlled by their members.

One such community, New Promise, began as a complex of buildings 60 miles outside of Moab, Utah. These buildings included living accommodations, a central meeting hall/library/theater, a food market, a health care station, and a network of gardens and walking trails, along with infrastructure buildings such as a water reclamation plant and a solar power station. Nearly all of its residents are able to work from home. Visitors are allowed only after a medical screening, and new members are admitted only after a rigorous screening process. Community dues are set at one-third of income, and the community is managed by a board of seven elected officials. There are two recorded instances of families being evicted from the original New Promise, in each case because, in the view of the governing board, they were not willing to abide by the decisions of the community.

New Promise offers a high standard of living and a buffer against both disease and political instability. In exchange, the community requires individuals to subordinate their own interests to those of the community. Applicants with strong religious or political ideologies are not admitted. Its members are typically highly-educated workers in technology, education, or business. “In New Promise you are free to do as you please,” said one member, “so long as what you’re doing doesn’t make anyone else miserable.” Read more »

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose.

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose. Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

by Paul Braterman

by Paul Braterman

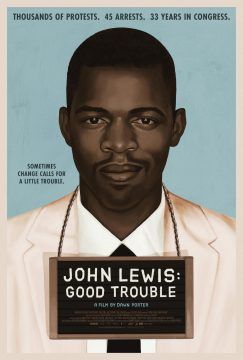

John Lewis: Good Trouble

John Lewis: Good Trouble