by Charlie Huenemann

Materialism is the view that everything that exists is made of matter. What’s matter? It’s hard to say with both precision and completeness, but it can’t be far off to think of matter as whatever can engage causally with the known forces of nature: gravity, electromagnetism, and atomic forces (strong and weak). If a thing responds to any of those forces, that thing is material. Of course, maybe there are some unknown forces of nature, and we’ll have to revise as they become known, but right now, this seems to be an adequate criterion for judging what counts as matter.

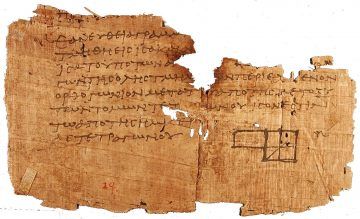

But I don’t think materialism is true, and it’s not because I believe in spirits or love or imagination or magic. It’s because of math. Math is a science of form: it explores the possible forms or properties or systems that are possible. Some of these possible structures, of course, describe the real systems we come across in our world, which is neat, and makes physics possible. But there are many, many more possibilities than are actual. It doesn’t take many beers before a gang of interested mathematicians will start describing all sorts of things that could never come to exist in our puny world because they are too big or complicated.

As the gang of mathematicians start describing these otherworldly possibilities, they are not just making stuff up. They can get things right, and get them wrong. It’s really hard to do math, because it’s all about proofs, which slide easily from validity into invalidity, or from coherence into incoherence, with a move as subtle as the fall of an eyelash. But communities of mathematicians keep one another in check, and what they do is as rigorous as any human endeavor can be.

So what about all these non-actual possibilities? If they are not just make-believe, what makes them genuine as possibilities? The best answer, I think, is that there are truths about structure, truths about form, which outrun all of the truths about matter. Our material world is the real-life version of a relatively small set of possible structures, but there is a much bigger world in existence, which is the one that math describes. Read more »

Our classes in the British university where I was teaching Pre-sessional students (mainly Chinese) were cancelled for a Special Event. Instead of their normal lessons on academic English, our students were shepherded off to witness a series of presentations on ‘learning.’ Learning, they were told, was ‘Collaborative,’ ‘Creative,’ and ‘Self-directed,’ and depended upon ‘Taking Responsibility for one’s own learning,’ ‘Thinking Critically,’ ‘Problem-solving’ and ‘Taking the Initiative.’

Our classes in the British university where I was teaching Pre-sessional students (mainly Chinese) were cancelled for a Special Event. Instead of their normal lessons on academic English, our students were shepherded off to witness a series of presentations on ‘learning.’ Learning, they were told, was ‘Collaborative,’ ‘Creative,’ and ‘Self-directed,’ and depended upon ‘Taking Responsibility for one’s own learning,’ ‘Thinking Critically,’ ‘Problem-solving’ and ‘Taking the Initiative.’ I began taking piano lessons when I was 8 years old, along with Lynn, my older and Mark, one of my brothers. Every Wednesday we’d walk together from school to a small storefront on Milwaukee Avenue about a half mile away. The store windows were covered in drapes, with a little sign indicating the teacher’s name and PIANO LESSONS. My sister gave her the $3 for three lessons, and we entered the small studio, which had a grand piano and a sofa, bookshelves, and a heavy, dusty drape separating the studio from the living quarters. We’d each wait patiently, doing our homework on the sofa while the other one had his or her lesson.

I began taking piano lessons when I was 8 years old, along with Lynn, my older and Mark, one of my brothers. Every Wednesday we’d walk together from school to a small storefront on Milwaukee Avenue about a half mile away. The store windows were covered in drapes, with a little sign indicating the teacher’s name and PIANO LESSONS. My sister gave her the $3 for three lessons, and we entered the small studio, which had a grand piano and a sofa, bookshelves, and a heavy, dusty drape separating the studio from the living quarters. We’d each wait patiently, doing our homework on the sofa while the other one had his or her lesson. We enjoyed learning the piano, but didn’t enjoy Mrs. K. She was creepy. We thought she might have been a Roma fortune teller or a magician, as she wore strange jewelry and shawls, and had Persian carpets and draperies around her studio. To us kids she looked about 90 years old (probably more like 40). She was actually a rather unsuccessful concert pianist, and memorabilia was scattered around the studio such as notices of performances and autographed pictures of famous conductors. She didn’t talk about it much her past life at all, as she was reduced to teaching piano lessons to the blue-collar neighborhood kids like ourselves. We persisted with lessons because we always did as we were told. We went home and put in our half-hour of practice on the second-hand but well-tuned piano that dad bought for us, and little by little we began to learn how to play.

We enjoyed learning the piano, but didn’t enjoy Mrs. K. She was creepy. We thought she might have been a Roma fortune teller or a magician, as she wore strange jewelry and shawls, and had Persian carpets and draperies around her studio. To us kids she looked about 90 years old (probably more like 40). She was actually a rather unsuccessful concert pianist, and memorabilia was scattered around the studio such as notices of performances and autographed pictures of famous conductors. She didn’t talk about it much her past life at all, as she was reduced to teaching piano lessons to the blue-collar neighborhood kids like ourselves. We persisted with lessons because we always did as we were told. We went home and put in our half-hour of practice on the second-hand but well-tuned piano that dad bought for us, and little by little we began to learn how to play.  America is a truck rolling down a hill towards a cliff. The downhill slope is the erosion of democratic norms; the cliff is the point where anti-democratic forces become powerful enough to crush democratic opposition by authoritarian means. The re-election of Donald Trump would very likely see the country sail over that cliff.

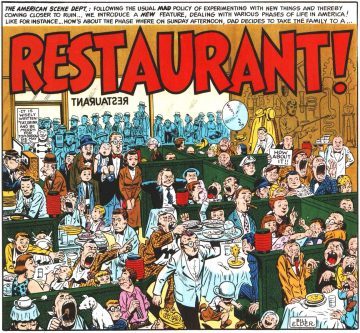

America is a truck rolling down a hill towards a cliff. The downhill slope is the erosion of democratic norms; the cliff is the point where anti-democratic forces become powerful enough to crush democratic opposition by authoritarian means. The re-election of Donald Trump would very likely see the country sail over that cliff.

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting

On November 11, 2019, I wrote a

On November 11, 2019, I wrote a