by David Kordahl

Last month I worked on a modern sort of archaeological dig, going through the equipment in a college physics lab to see what sorts of devices were on hand. It reminded me of being a little kid, when I would tiptoe around my dad’s religious paraphernalia (he was a Lutheran pastor), not really knowing what everything was for, but being sure that each item had a definite purpose. My job in the lab was to construct setups for a modern physics course, demos for students to learn a few things about the empirical basis of special relativity and quantum theory, to cut through the layers of interpretative bullshit. Encountering unfamiliar items, I would rummage around for their service manuals, pushing aside brittle O-rings and chipped pipettes, stacking old printouts, believing without proof that the lab’s former occupants had found some use for these treasures.

In bed one night after a long day with the machines, it occurred to me that these educational toys might share some common purpose with the portable communion kits and illustrated Bibles of my childhood. In each case, the devices were technologies designed to strengthen belief in a distinct mask for the world of observed phenomena. And in each case, strengthened beliefs hold for believers the promise of new ways to navigate the world, ways that non-believers can neither appreciate nor access.

This is not to deny the obvious differences between a communion kit and a current amplifier. One obvious feature of technology is that it’s mostly belief-proof. Almost no one understands all the devices that they use, and many users hold views that explicitly contradict the theories used to construct the devices on which they rely. (Teaching high school science, I met smartphone savants who were supremely confident in the irrelevance of physics to their lives.) Yet the fact that I now entertained the possibility that my lab setups had anything to do with religious conversion already proved that I’d strayed pretty far from my early days. Read more »

It’s Monday, 1:45, and six men and I sit in a circle with our German-trained psychotherapist, an imperious woman who reminds us that she is here to help only if we get bogged down or offer guidance and that we men need to find our own way through our turmoil, which is the point of the group and the point of each of us paying $3000 per year. I’m fairly new, so before I speak, I’m seeking some level of comfort or commonality among us, and every week I come up short. I’m not yet adjusted and unsure what I should be adjusting to.

It’s Monday, 1:45, and six men and I sit in a circle with our German-trained psychotherapist, an imperious woman who reminds us that she is here to help only if we get bogged down or offer guidance and that we men need to find our own way through our turmoil, which is the point of the group and the point of each of us paying $3000 per year. I’m fairly new, so before I speak, I’m seeking some level of comfort or commonality among us, and every week I come up short. I’m not yet adjusted and unsure what I should be adjusting to.

We are entering the aftermath. Two of the most epic and wrenching struggles in American history are finally playing out to their conclusions. At last we see a conclusive democratic rejection of a presidency built on systematic lying and racism. At the same time we look just weeks or months ahead for vaccines that will liberate us from our deadly yearlong pandemic.

We are entering the aftermath. Two of the most epic and wrenching struggles in American history are finally playing out to their conclusions. At last we see a conclusive democratic rejection of a presidency built on systematic lying and racism. At the same time we look just weeks or months ahead for vaccines that will liberate us from our deadly yearlong pandemic. A Task for the Left

A Task for the Left

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon.

The first time I ever left home without leaving home I was twelve years old, recently back from a winter trip to Mexico. Routinely sent to bed at 8 pm (my parents were old and old-fashioned), always wondering how to fill the inevitable two hours of insomnia, I opted to return to Mexico, not as the sleepless chiquita that I was, but as the fierce guerilla chief I would become in the narrative, leading a band of outlaw Aztecs in raids against a host of injustices from base camp in a desert. No precedents existed for my leadership skills in real life, but within the carefully sculpted storyline of the daydream, I was both charismatic and respected, not merely proficient but also inspired, a warrior queen to rival any Amazon. In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow.

In the summer of 2000, after completing my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I had to decide where to go next. I could either take up a job offer at a motorcycle manufacturing plant in south India, or I could, like many of my college friends, head to a university in the United States. Most of my friends had assistantships and tuition waivers. I had been admitted to a couple of state universities but did not have any financial support. Out a feeling that if I stayed back in India, I’d be ‘left behind’ – whatever that meant: it was only a trick of the mind, left unexamined – I took a risk, and decided to try graduate school at Arizona State University. I hoped that funding would work out somehow. One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

One of the most interesting and memorable characters in sci-fi films is the

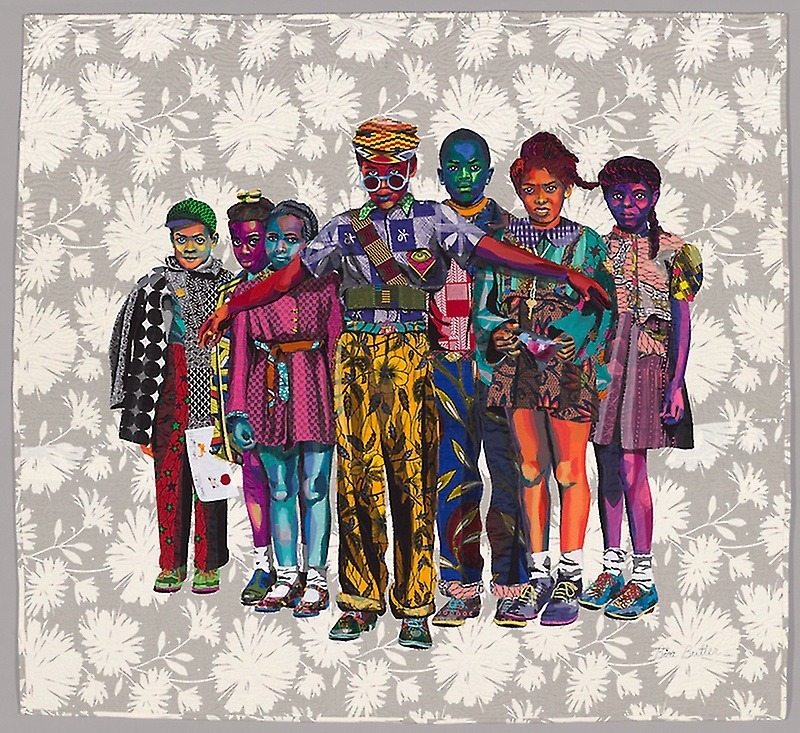

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

Bisa Butler. The Safety Patrol. 2018.

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”

On 9 October 1990, President George H.W. Bush held a news conference about Iraqi-occupied Kuwait as the US was building an international coalition to liberate the emirate. He said: “I am very much concerned, not just about the physical dismantling but about some of the tales of brutality. It’s just unbelievable, some of the things. I mean, people on a dialysis machine cut off; babies heaved out of incubators and the incubators sent to Baghdad … It’s sickening.”