by Tim Sommers

A libertarian. Old joke. I mean, marijuana is not even illegal in a lot of states anymore. How about this one? A libertarian walks into a bear. Okay, that’s not really a joke. It’s the title of a recent book by Matthew Honogoltz-Hetling, subtitled “The Utopian Plot to Liberate an American Town (And Some Bears)”. It’s about a group of libertarians who move to a rural town with the express purpose of dismantling the local government and producing a libertarian utopia. The resulting problems with coordinating refuse disposal attract a lot of bears and the lack of a government makes it difficult to mount a response. Bears 1. Libertarians 0.

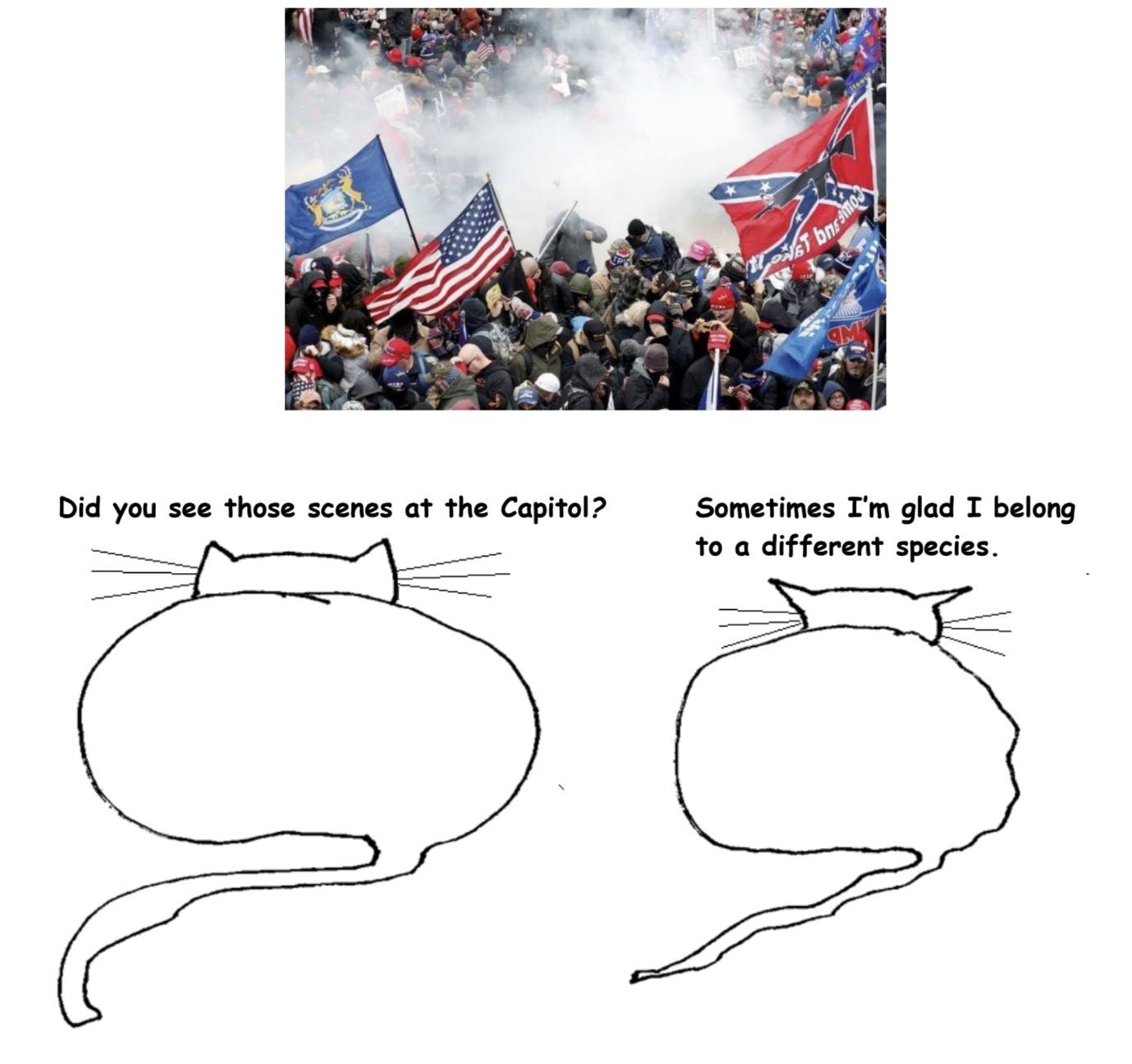

I have been thinking about libertarianism again since I read Thomas Wells’ smart 3 Quarks Daily article Libertarianism is Bankrupt arguing that libertarianism, “like Marxism or Flat-Earthism”, has “nothing to offer”. Which is kind of unfair to Marxism if you ask me. But a real-world example of how dead the libertarian horse is, is offered by the departure of many recovering libertarians from the Cato Institute recently, the bulk of them forming a new non-libertarian think tank (Nikensas). What lead most of these former Cato staffers to abandon libertarianism was the existence of a political problem that they felt libertarianism had no response to. I bet you can guess what it is. (I’ll tell you at the end, just in case.)

In the meantime, given the moribund state of libertarianism, rather than beat on it some more, I thought it would be fun to return to its glory days, to Robert Nozick and his book Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Nozick was arguably the most philosophically sophisticated libertarian ever. He was charismatic. He was purportedly widely read in the Reagan White House. And he was lauded as one of the Philosopher Kings of Harvard by Esquire Magazine in 1983 (including a full-page photospread in which he looked very thoughtful). (The other Philosopher-King, John Rawls, refused to be interviewed or photographed for the piece.) Read more »

Abstract: This article, written by the Digital Philosophy Group of TU Delft is inspired by the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma. It is not a review of the show, but rather uses it as a lead to a wide-ranging philosophical piece on the ethics of digital technologies. The underlying idea is that the documentary fails to give an impression of how deep the ethical and social problems of our digital societies in the 21st century actually are; and it does not do sufficient justice to the existing approaches to rethinking digital technologies. The article is written, we hope, in an accessible and captivating style. In the first part (“the problems”), we explain some major issues with digital technologies: why massive data collection is not only a problem for privacy but also for democracy (“nothing to hide, a lot to lose”); what kind of knowledge AI produces (“what does the Big Brother really know”) and is it okay to use this knowledge in sensitive social domains (“the risks of artificial judgement”), why we cannot cultivate digital well-being individually (“with a little help from my friends”), and how digital tech may make persons less responsible and create a “digital Nuremberg”. In the second part (“The way forward”) we outline some of the existing philosophical approaches to rethinking digital technologies: design for values, comprehensive engineering, meaningful human control, new engineering education, and a global digital culture.

Abstract: This article, written by the Digital Philosophy Group of TU Delft is inspired by the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma. It is not a review of the show, but rather uses it as a lead to a wide-ranging philosophical piece on the ethics of digital technologies. The underlying idea is that the documentary fails to give an impression of how deep the ethical and social problems of our digital societies in the 21st century actually are; and it does not do sufficient justice to the existing approaches to rethinking digital technologies. The article is written, we hope, in an accessible and captivating style. In the first part (“the problems”), we explain some major issues with digital technologies: why massive data collection is not only a problem for privacy but also for democracy (“nothing to hide, a lot to lose”); what kind of knowledge AI produces (“what does the Big Brother really know”) and is it okay to use this knowledge in sensitive social domains (“the risks of artificial judgement”), why we cannot cultivate digital well-being individually (“with a little help from my friends”), and how digital tech may make persons less responsible and create a “digital Nuremberg”. In the second part (“The way forward”) we outline some of the existing philosophical approaches to rethinking digital technologies: design for values, comprehensive engineering, meaningful human control, new engineering education, and a global digital culture.

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in people’s standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in people’s everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations’ citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book “Religion and the Rise of Capitalism”. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Tragically, President Biden’s 21-page “

Tragically, President Biden’s 21-page “

Jesus is reported to have critiqued the seventh commandment as follows:

Jesus is reported to have critiqued the seventh commandment as follows: