by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

Like clockwork, every year around the spring equinox, the ducks and egrets would return to the river in Tochigi. And sprigs of green grass would start sprouting in our lawn. This was when people started taking to the hills to pick mountain vegetables, herbs, and other wild foods. My son loved looking for ferns and fiddleheads. In Japan, this meant warabi (bracken fern), zenmai (osmund or cinnamon fern) and kogomi (ostrich fern). We enjoyed going “baby fern hunting.” The delicacies could be found along a trail a bike-ride away from our house. Like little coiled springs, the fiddleheads seemed waiting for just the right moment to unfurl.

Old like dragonflies, ferns once covered prehistoric forests. My son and I loved imagining ourselves wandering in a never-ending fern forest as gigantic dinosaurs soared in the skies above our heads. The mist-covered hill near our house, just waking up from winter was the home of fiddleheads, lilies and dogtooth violets. And there was an ancient shrine standing guard at the summit.

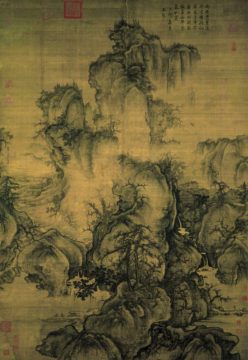

“Mountains smiling in early spring” –Borrowed like so many things from China, the poetic trope was made famous in Japan by the Northern Song painter Guo Xi, whose poem about mountains smiling and laughing in spring appeared in an poetry anthology in Japanese known as 漢詩集 「臥遊録」 Chinese Poetry Anthology Dream Journey Jottings:

春山淡治而如笑

夏山蒼翠而如滴

秋山明浄而如粧

冬山惨淡而如眠

“Mountains smiling in early spring” was an image much appreciated in Japanese haiku. After what must have felt like an unendingly long period of cold and depressing “mountains sleeping,” the mountains in March would seem to almost “spring” to life again.

笑= can mean smiling and/or laughing: oh, how this has tormented translators of Japanese and Chinese… Read more »

I discovered my ideal radio station by accident.

I discovered my ideal radio station by accident.

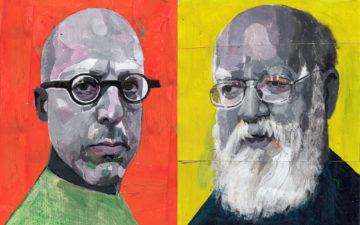

I’ll return to that second crack once we’ve explored the first one. But why do that at all? Does free will matter to anyone but a couple of bickering philosophers? Of course it does! Sam Harris noted in his recent

I’ll return to that second crack once we’ve explored the first one. But why do that at all? Does free will matter to anyone but a couple of bickering philosophers? Of course it does! Sam Harris noted in his recent  “Sadequain!” The very name is like a magic word that triggers a tumult of images in the mind. Arguably, no Pakistani artist has elicited more admiration, evoked more passion, and received more adulation than Saiyid Sadquain Ahmad Naqvi, the subject – and really, the hero – of the book “Sadequain: Artist and Poet – A Memoir” by Saiyid Ali Naqvi. In the world of art, be it painting, music, or literature, it is the pinnacle of achievement to be recognized by a single name – to need no further introduction. And rare indeed is the artist who achieves this distinction in his or her own life, as Sadequain did remarkably early in his career as an artist. And this delightful, beautiful, and insightful book shows why. Beginning with the earliest and formative years of Sadequain when he was not yet a legend, it takes the reader systematically through all stages of his life and his growth as an artist, laying bare both the immense determination and the perpetual restlessness of the artist’s genius.

“Sadequain!” The very name is like a magic word that triggers a tumult of images in the mind. Arguably, no Pakistani artist has elicited more admiration, evoked more passion, and received more adulation than Saiyid Sadquain Ahmad Naqvi, the subject – and really, the hero – of the book “Sadequain: Artist and Poet – A Memoir” by Saiyid Ali Naqvi. In the world of art, be it painting, music, or literature, it is the pinnacle of achievement to be recognized by a single name – to need no further introduction. And rare indeed is the artist who achieves this distinction in his or her own life, as Sadequain did remarkably early in his career as an artist. And this delightful, beautiful, and insightful book shows why. Beginning with the earliest and formative years of Sadequain when he was not yet a legend, it takes the reader systematically through all stages of his life and his growth as an artist, laying bare both the immense determination and the perpetual restlessness of the artist’s genius.

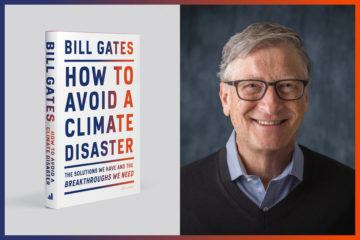

The world we live in is changing, and our politics must change with it. We are in what has been called the ‘anthropocene’: the period in which human activity is threatening the ecosystem on which we all depend. Catastrophic climate change threatens our very survival. Yet our political class seems unable to take the necessary steps to avert it. Add to that the familiar and pressing problems of massive inequality, exploitation, systemic racism and job insecurity due to automation and the relocation of production to cheaper labour markets, and we have a truly global and multidimensional set of problems. It is one that our political masters seem unable to properly confront. Yet confront them they, and we, must. Such is the scale of the problem, the political order needs wholesale change, rather than the small, incremental reforms we have been taught are all that are practicable or desirable. And change, whether we like it or not is coming anyway: between authoritarian national conservative regimes, which with all the inequality, xenophobia, or that of a democratic, green post-capitalism. The thing that won’t survive is liberalism.

The world we live in is changing, and our politics must change with it. We are in what has been called the ‘anthropocene’: the period in which human activity is threatening the ecosystem on which we all depend. Catastrophic climate change threatens our very survival. Yet our political class seems unable to take the necessary steps to avert it. Add to that the familiar and pressing problems of massive inequality, exploitation, systemic racism and job insecurity due to automation and the relocation of production to cheaper labour markets, and we have a truly global and multidimensional set of problems. It is one that our political masters seem unable to properly confront. Yet confront them they, and we, must. Such is the scale of the problem, the political order needs wholesale change, rather than the small, incremental reforms we have been taught are all that are practicable or desirable. And change, whether we like it or not is coming anyway: between authoritarian national conservative regimes, which with all the inequality, xenophobia, or that of a democratic, green post-capitalism. The thing that won’t survive is liberalism.

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily.

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily.