by Mindy Clegg

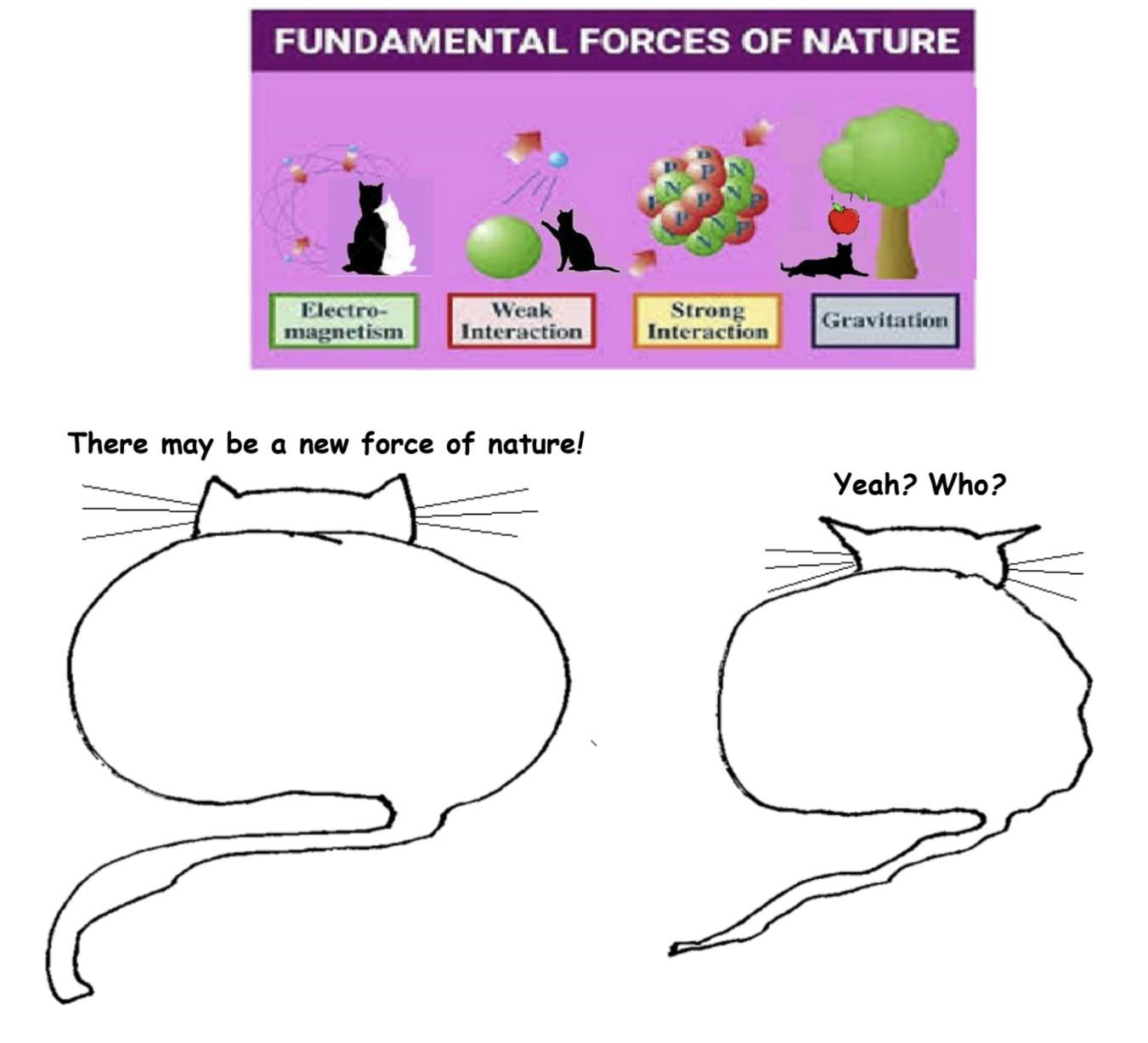

By now over 100,000,000 Americans have received the Covid-19 vaccine and we seem on track to double that by the end of President Biden’s hundredth day. Efforts to reach herd immunity continue apace with many states opening up access to more groups in recent weeks. It’s a hopeful feeling, seeing more people receiving this promise of a return to normality. But some dark clouds are obscuring this (global) goal of herd immunity. We might see yet another surge before we’re done, both here and in other countries. Many of the states struggling to get their populations vaccinated have begun to roll back various mandates for distancing, masking, and capacity limits in businesses. There is still a vocal minority who continue to insist that masking and distancing are useless “health theater”, a direct threat to our civil liberties, that Covid-19 is no worse than the flu, and will refuse getting the vaccine as it’s “their body” (ignoring how their actions impact others in their communities).

This vaccine hesitancy—which despite the media narrative that it’s prevalent among Black Americans is really now a problem among white Republicans—can easily disrupt our goal of herd immunity and draw out the liminal state many of us have been living through. This hesitancy stems from a longer history of initially pro-health, anti-corporate movements that have been twisted and weaponized. As a result, the people who have been historically hurt the most by our government and other institutions are now suffering the most. Their pro-life rhetoric only extends to theoretical life, not to actual humans already alive and in need of support and protection via widespread vaccinations. Here I argue that skepticism of government and even corporations has become weaponized to a dangerous degree, even when it comes to settled science such as vaccinations. Read more »

I don’t think I saw an actual daffodil until I was 19, although I had admired the many varieties I saw pictured in bulb catalogs and even—I hesitate to admit this—written haiku about daffodils (at 14, in an English class). When my first husband and I drove through Independence, Missouri, early in our marriage, I saw my first daffodils, a large clump tossing their heads in a sunshiny breeze. Wordsworth flashed upon my inner ear, and as I remember it, I recited “And then my heart with pleasure fills, and dances with the daffodils!” (If I did in fact say that, I’m sure I added the gratuitous exclamation point.) My husband, who was driving, gently asked me to return my attention to the map (I was navigating).

I don’t think I saw an actual daffodil until I was 19, although I had admired the many varieties I saw pictured in bulb catalogs and even—I hesitate to admit this—written haiku about daffodils (at 14, in an English class). When my first husband and I drove through Independence, Missouri, early in our marriage, I saw my first daffodils, a large clump tossing their heads in a sunshiny breeze. Wordsworth flashed upon my inner ear, and as I remember it, I recited “And then my heart with pleasure fills, and dances with the daffodils!” (If I did in fact say that, I’m sure I added the gratuitous exclamation point.) My husband, who was driving, gently asked me to return my attention to the map (I was navigating).

In 1887 Ludwik Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist and amateur linguist, published in Warsaw a small volume entitled Unua Libro. Its aim was to introduce his newly invented language, in which ‘Unua Libro’ means ‘First Book.’ Zamenhof used the pseudonym ‘Doktor Esperanto’ and the language took its name from this word, which means ‘one who hopes.’ The picture shows Zamenhof (front row) at the First International Esperanto Congress in Boulogne in 1905.

In 1887 Ludwik Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist and amateur linguist, published in Warsaw a small volume entitled Unua Libro. Its aim was to introduce his newly invented language, in which ‘Unua Libro’ means ‘First Book.’ Zamenhof used the pseudonym ‘Doktor Esperanto’ and the language took its name from this word, which means ‘one who hopes.’ The picture shows Zamenhof (front row) at the First International Esperanto Congress in Boulogne in 1905.

If, for a long time now, you’ve been getting up early in the morning, setting off to school or your workplace, getting there at the required time, spending the day performing your assigned tasks (with a few scheduled breaks), going home at the pre-ordained time, spending a few hours doing other things before bedtime, then getting up the next morning to go through the same routine, and doing this most days of the week, most weeks of the year, most years of your life, then the working life in its modern form is likely to seem quite natural. But a little knowledge of history or anthropology suffices to prove that it ain’t necessarily so.

If, for a long time now, you’ve been getting up early in the morning, setting off to school or your workplace, getting there at the required time, spending the day performing your assigned tasks (with a few scheduled breaks), going home at the pre-ordained time, spending a few hours doing other things before bedtime, then getting up the next morning to go through the same routine, and doing this most days of the week, most weeks of the year, most years of your life, then the working life in its modern form is likely to seem quite natural. But a little knowledge of history or anthropology suffices to prove that it ain’t necessarily so. It’s official: Lilly Singh, the YouTube phenomenon,

It’s official: Lilly Singh, the YouTube phenomenon,

Marlène Huissoud. A3 Drawings 8, 2020.

Marlène Huissoud. A3 Drawings 8, 2020.

Patriotism is a contested ideal in the culture war which bubbles away in the UK. It’s worth examining not only as an idea in itself but also with regards to how it is understood and expressed in the present cultural context of the UK. It seems to me that the debate is dominated by two ends of a spectrum, both misguided. At one end there are those who find the word itself too problematic to be worth salvaging. It is, they would argue, despite claims to the contrary, unavoidably linked to its ugly cousin, nationalism, with its xenophobic and jingoist associations.

Patriotism is a contested ideal in the culture war which bubbles away in the UK. It’s worth examining not only as an idea in itself but also with regards to how it is understood and expressed in the present cultural context of the UK. It seems to me that the debate is dominated by two ends of a spectrum, both misguided. At one end there are those who find the word itself too problematic to be worth salvaging. It is, they would argue, despite claims to the contrary, unavoidably linked to its ugly cousin, nationalism, with its xenophobic and jingoist associations.