by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Academic journal publishing employs a system of anonymous peer review. Work is submitted anonymously to a journal, which then arranges for it to be reviewed by other experts in the field, who also remain anonymous. The reviewers compose a report that itemizes the submission’s merits and flaws, and eventually recommending publication, rejection, or revision-and-resubmission. The reports are shared with the submitting academic, along with a final judgment about whether the work will be published.

Every academic has stories about how this process can go haywire. Many of these stories have to do with that one reviewer, the one who seemed hell-bent on not only misunderstanding but willfully resisting the point of an essay, the one who wrote an off-the-rails, and just nasty, rebuke of the submission. The anonymous peer review process at academic journals, it seems, encourages this kind of behavior. Not only does the reviewer not know who the author is, but the author will not know who the reviewer is. And all the intuitions shared about how anonymity on the internet produces trolls bear on temptations too many reviewers give in to.

Most journal reviewing, in the humanities at least, is done without compensation. It is a service to the profession, added on to one’s teaching, university service, and research responsibilities. And it shows up out of the blue, with a short invitation from a journal editor and maybe an abstract. It’s often onerous, and too often simply annoying. In the climate of publish or perish, many essays go out to the journals before they are ready, and in fields with fast-moving controversies, they must or else be untimely. So reviewers are faced with essays that are additions to their already heavy workloads that could have used more time. And the inclination to take one’s frustrations out on the author is just too great. Add to all of this the simple but pathological delight of punching those who cannot defend themselves or hit back. We have been on the helpless receiving end of such pummeling. Many times. Read more »

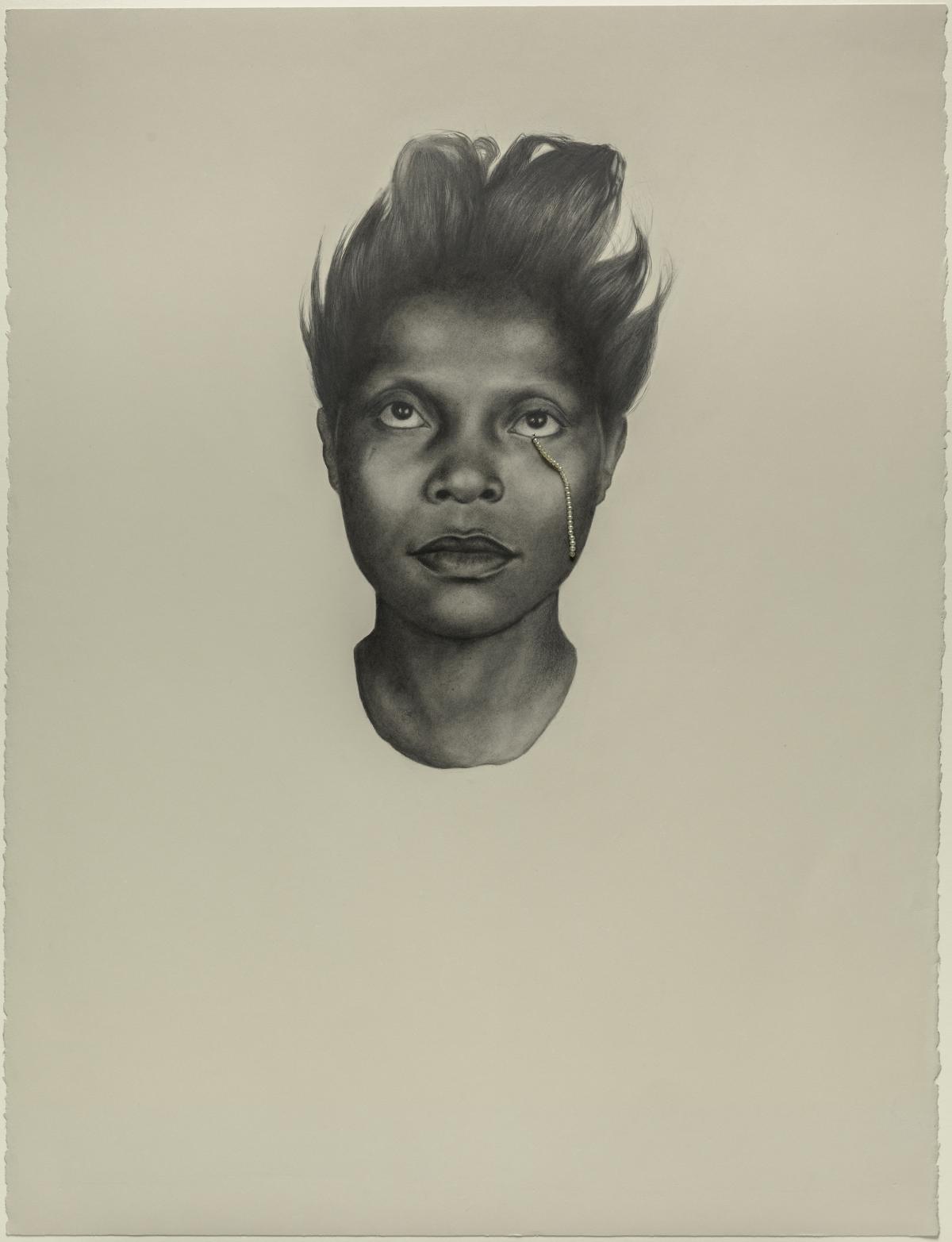

Whitfield Lovell. Kin XLV (Das Lied von der Erde), 2011.

Whitfield Lovell. Kin XLV (Das Lied von der Erde), 2011. Not long ago, having steeled myself for the read-through of yet another dry but informative assessment of the body’s immune response to Covid 19 and her variant offspring, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself being dragged into a barbaric tale of murder and mayhem, full of gory details and dire strategies.

Not long ago, having steeled myself for the read-through of yet another dry but informative assessment of the body’s immune response to Covid 19 and her variant offspring, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself being dragged into a barbaric tale of murder and mayhem, full of gory details and dire strategies. We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book, Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes (Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle), threw what seemed to be a pebble into the world of linguistics – but it is a pebble whose ripples have continued to expand. This might be thought surprising, in view of its curious construction. It contains a detailed description of the writer’s encounters with a small, remote Amazonian tribe, whom he calls the Pirahã (pronounced something like ‘Pidahañ’), but who apparently call themselves the Hi’aiti’ihi, roughly translated as “the straight ones.” They live beside the Maici River, a tributary of a tributary of the Amazon, which is nonetheless two hundred metres wide at its mouth.

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book, Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes (Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle), threw what seemed to be a pebble into the world of linguistics – but it is a pebble whose ripples have continued to expand. This might be thought surprising, in view of its curious construction. It contains a detailed description of the writer’s encounters with a small, remote Amazonian tribe, whom he calls the Pirahã (pronounced something like ‘Pidahañ’), but who apparently call themselves the Hi’aiti’ihi, roughly translated as “the straight ones.” They live beside the Maici River, a tributary of a tributary of the Amazon, which is nonetheless two hundred metres wide at its mouth. Sometime before Ashok Rudra and I started on our large-scale data collection, I was already doing some theoretical and conceptual work on agrarian relations. My first, mainly theoretical, paper on share-cropping (jointly with TN) came out in American Economic Review in 1971. That paper was unsatisfactory and had quite a few loose strands, but it was one of the first papers to look theoretically into an economic-institutional arrangement of a developing country at the micro-level. This was a time when development economics was preoccupied with macro-issues like the structural transformation of the whole economy involving transition from agriculture to industrialization or problems of its aggregate interaction with more developed economies.

Sometime before Ashok Rudra and I started on our large-scale data collection, I was already doing some theoretical and conceptual work on agrarian relations. My first, mainly theoretical, paper on share-cropping (jointly with TN) came out in American Economic Review in 1971. That paper was unsatisfactory and had quite a few loose strands, but it was one of the first papers to look theoretically into an economic-institutional arrangement of a developing country at the micro-level. This was a time when development economics was preoccupied with macro-issues like the structural transformation of the whole economy involving transition from agriculture to industrialization or problems of its aggregate interaction with more developed economies. A provocative title, perhaps, and perhaps also counterintuitive. One thinks in the language one speaks, everybody knows that. Why would anyone ask bilingual speakers which language they think in (or dream in) otherwise?

A provocative title, perhaps, and perhaps also counterintuitive. One thinks in the language one speaks, everybody knows that. Why would anyone ask bilingual speakers which language they think in (or dream in) otherwise? The slim, green book Natural History of Western Massachusetts is one of my favorites. Compressed into its hundred odd pages are articles and visuals that describe the essential natural features of the Amherst region, where I’ve lived since 2008. I turn to it every time something outdoors piques my interest — a new tree, bird or mammal, a geological feature.

The slim, green book Natural History of Western Massachusetts is one of my favorites. Compressed into its hundred odd pages are articles and visuals that describe the essential natural features of the Amherst region, where I’ve lived since 2008. I turn to it every time something outdoors piques my interest — a new tree, bird or mammal, a geological feature. Everything in the universe that’s visible from your location on Earth passes by overhead every day. We’re usually able see only the stars, galaxies, planets, and so on that are in the sky when the sun is not; we become aware of them when the sun sets and Earth’s shadow rises from the eastern horizon. But all of them are there at some point in the day. We picnic beneath the winter constellation Orion in summer and walk beneath the Summer Triangle on the short days of winter. The moon also crosses the sky every day, sometimes in the daytime, and sometimes too close to the sun to be seen.

Everything in the universe that’s visible from your location on Earth passes by overhead every day. We’re usually able see only the stars, galaxies, planets, and so on that are in the sky when the sun is not; we become aware of them when the sun sets and Earth’s shadow rises from the eastern horizon. But all of them are there at some point in the day. We picnic beneath the winter constellation Orion in summer and walk beneath the Summer Triangle on the short days of winter. The moon also crosses the sky every day, sometimes in the daytime, and sometimes too close to the sun to be seen. I had my first panic attack at age sixteen, which was (deargod) over 35 years ago. It happened during school, much to my teenage mortification. Some friends and I were hanging out in our high school newspaper office during a free period, sprawled on one of the crapped-out couches under the blinking fluorescent lights, just shooting the shit. All of a sudden, a wave of horror swept over me—no, that’s not the right word. It was a feeling of fear mixed with a kind of existential dread, washing over me in waves, and then my heart was pounding, the walls were closing in, and I was gripped with an intense feeling of unreality. (This is something that people with panic disorder don’t often explain—or maybe it’s different for everyone. But for me the worst part of a panic attack is the

I had my first panic attack at age sixteen, which was (deargod) over 35 years ago. It happened during school, much to my teenage mortification. Some friends and I were hanging out in our high school newspaper office during a free period, sprawled on one of the crapped-out couches under the blinking fluorescent lights, just shooting the shit. All of a sudden, a wave of horror swept over me—no, that’s not the right word. It was a feeling of fear mixed with a kind of existential dread, washing over me in waves, and then my heart was pounding, the walls were closing in, and I was gripped with an intense feeling of unreality. (This is something that people with panic disorder don’t often explain—or maybe it’s different for everyone. But for me the worst part of a panic attack is the  Sughra Raza. Another Morning. Venice, July 2012.

Sughra Raza. Another Morning. Venice, July 2012.