by Bill Murray

Ukraine is surrounded by 100,000-plus miserable, freezing, foot-stamping Russian soldiers who are Chekov’s gun on the table in Act One of our new post-Cold War epic. We’ve moved from “surely he wouldn’t?” to “he’s really going to, isn’t he?” It’s the moment when Wile E. Coyote has run off the cliff but not yet begun to fall.

Two years ago Covid crowded out every thing but the most immediate, every body but family. Shocked by the viral invader’s audacity, we scrambled around in a new, unfamiliar world. Everything was frightening. We had precious little time to reflect.

Now comes the malign intent of a real-life invader. Unlike Covid, Ukraine isn’t exactly appearing out of nowhere. Russia has been moving toward military aggression for months. The US president has had time to commit high profile gaffes about any U.S. response. Russian landing craft have moved clear around Europe from the Baltic Sea to threaten Ukraine in the Black Sea. We’ve had ample opportunity to reflect.

So far the west has performed a pretty nifty feat – defying physics. Specifically Newton’s third law, the one about for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. Only now, at last, comes a grudging rumble from the big American reaction machine. Read more »

The Naxalite phase in Bengal was a short, tragic chapter in politics, but in Bengal’s cultural-emotional life its implications were deeper, and reflected in its literature (and films)—most poignantly yet forcefully captured by the writer Mahshweta Devi, one of Bengal’s most powerful political novelists. Again and again in the 20th century some of Bengali youth have been fascinated by the romanticism of revolutionary violence–as was the case in the early decades in the freedom struggle against the British (I have earlier mentioned about my maternal uncle caught in its vortex), then again in the 1940’s when the sharecroppers’ movement (called tebhaga) was soon followed by a period of communist insurgency in 1948-50, and then in the Naxalite movement of the late 60’s and early 70’s.

The Naxalite phase in Bengal was a short, tragic chapter in politics, but in Bengal’s cultural-emotional life its implications were deeper, and reflected in its literature (and films)—most poignantly yet forcefully captured by the writer Mahshweta Devi, one of Bengal’s most powerful political novelists. Again and again in the 20th century some of Bengali youth have been fascinated by the romanticism of revolutionary violence–as was the case in the early decades in the freedom struggle against the British (I have earlier mentioned about my maternal uncle caught in its vortex), then again in the 1940’s when the sharecroppers’ movement (called tebhaga) was soon followed by a period of communist insurgency in 1948-50, and then in the Naxalite movement of the late 60’s and early 70’s.

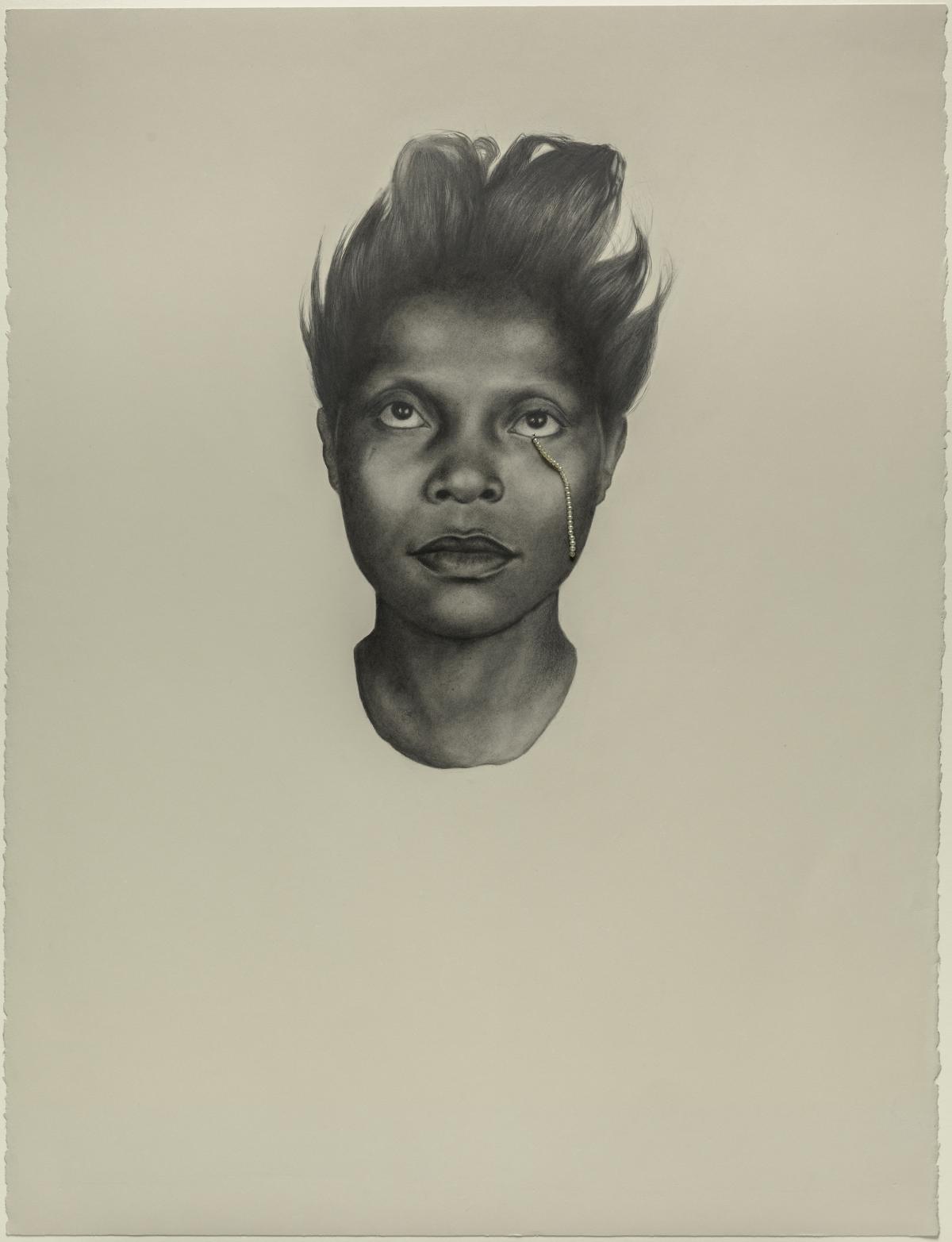

Whitfield Lovell. Kin XLV (Das Lied von der Erde), 2011.

Whitfield Lovell. Kin XLV (Das Lied von der Erde), 2011. Not long ago, having steeled myself for the read-through of yet another dry but informative assessment of the body’s immune response to Covid 19 and her variant offspring, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself being dragged into a barbaric tale of murder and mayhem, full of gory details and dire strategies.

Not long ago, having steeled myself for the read-through of yet another dry but informative assessment of the body’s immune response to Covid 19 and her variant offspring, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself being dragged into a barbaric tale of murder and mayhem, full of gory details and dire strategies. We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book, Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes (Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle), threw what seemed to be a pebble into the world of linguistics – but it is a pebble whose ripples have continued to expand. This might be thought surprising, in view of its curious construction. It contains a detailed description of the writer’s encounters with a small, remote Amazonian tribe, whom he calls the Pirahã (pronounced something like ‘Pidahañ’), but who apparently call themselves the Hi’aiti’ihi, roughly translated as “the straight ones.” They live beside the Maici River, a tributary of a tributary of the Amazon, which is nonetheless two hundred metres wide at its mouth.

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book, Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes (Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle), threw what seemed to be a pebble into the world of linguistics – but it is a pebble whose ripples have continued to expand. This might be thought surprising, in view of its curious construction. It contains a detailed description of the writer’s encounters with a small, remote Amazonian tribe, whom he calls the Pirahã (pronounced something like ‘Pidahañ’), but who apparently call themselves the Hi’aiti’ihi, roughly translated as “the straight ones.” They live beside the Maici River, a tributary of a tributary of the Amazon, which is nonetheless two hundred metres wide at its mouth. A provocative title, perhaps, and perhaps also counterintuitive. One thinks in the language one speaks, everybody knows that. Why would anyone ask bilingual speakers which language they think in (or dream in) otherwise?

A provocative title, perhaps, and perhaps also counterintuitive. One thinks in the language one speaks, everybody knows that. Why would anyone ask bilingual speakers which language they think in (or dream in) otherwise? The slim, green book Natural History of Western Massachusetts is one of my favorites. Compressed into its hundred odd pages are articles and visuals that describe the essential natural features of the Amherst region, where I’ve lived since 2008. I turn to it every time something outdoors piques my interest — a new tree, bird or mammal, a geological feature.

The slim, green book Natural History of Western Massachusetts is one of my favorites. Compressed into its hundred odd pages are articles and visuals that describe the essential natural features of the Amherst region, where I’ve lived since 2008. I turn to it every time something outdoors piques my interest — a new tree, bird or mammal, a geological feature. Everything in the universe that’s visible from your location on Earth passes by overhead every day. We’re usually able see only the stars, galaxies, planets, and so on that are in the sky when the sun is not; we become aware of them when the sun sets and Earth’s shadow rises from the eastern horizon. But all of them are there at some point in the day. We picnic beneath the winter constellation Orion in summer and walk beneath the Summer Triangle on the short days of winter. The moon also crosses the sky every day, sometimes in the daytime, and sometimes too close to the sun to be seen.

Everything in the universe that’s visible from your location on Earth passes by overhead every day. We’re usually able see only the stars, galaxies, planets, and so on that are in the sky when the sun is not; we become aware of them when the sun sets and Earth’s shadow rises from the eastern horizon. But all of them are there at some point in the day. We picnic beneath the winter constellation Orion in summer and walk beneath the Summer Triangle on the short days of winter. The moon also crosses the sky every day, sometimes in the daytime, and sometimes too close to the sun to be seen.