by Steven Gimbel and Gwydion Suilebhan

As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch new, seemingly undeniable video evidence of insurrection and quibble about whether one could reach the steering wheel of the Presidential SUV from the back seat, the ideas of Thomas Kuhn, the philosopher and historian of science who coined the phrase “paradigm shift” to explain scientific revolutions remain prescient as ever, even as we approach his 100th birthday.

As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch new, seemingly undeniable video evidence of insurrection and quibble about whether one could reach the steering wheel of the Presidential SUV from the back seat, the ideas of Thomas Kuhn, the philosopher and historian of science who coined the phrase “paradigm shift” to explain scientific revolutions remain prescient as ever, even as we approach his 100th birthday.

According to Kuhn in his most famous work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, scientists generally think and work in a state of what he called normal science. Under normal scientific conditions, all research occurs within a paradigm. Paradigms, he explained, do four interrelated things.

First, they define the terms that describe the universe, like atom or force. Second, they determine what counts as legitimate questions. (“What is the mass of the electron?” might be fair, for example, but not “Do electrons have polka-dots?”) Third, they set limits on which tools you can use to answer those questions. (Reading a voltmeter is perfectly acceptable, but reading tea leaves is out.) And fourth, they determine what counts as an acceptable answer to those questions. (Just to pick one: you don’t get to use negative lengths.)

Normal science is puzzle solving. The paradigm frames riddles and gives us the rules we need to follow in order to solve them. If you solve an approved riddle, you get to publish your answer, becoming a member of the community of normal scientists. The paradigm gives members of the scientific community their union cards, essentially, so the last thing they want to do is to question the rules of that paradigm. Read more »

I knew it was coming, yet I was still surprised when it hit my classroom.

I knew it was coming, yet I was still surprised when it hit my classroom.  I think a lot about the fate of human civilization these days.

I think a lot about the fate of human civilization these days. Lorenza Böttner. Face Art, 1983.

Lorenza Böttner. Face Art, 1983.

Elections have consequences. Sometimes those consequences may be unintended, but they are always there. Elections have consequences. You can’t say it too many times because too many voters don’t act if they believe it. They should. Elections have consequences.

Elections have consequences. Sometimes those consequences may be unintended, but they are always there. Elections have consequences. You can’t say it too many times because too many voters don’t act if they believe it. They should. Elections have consequences.

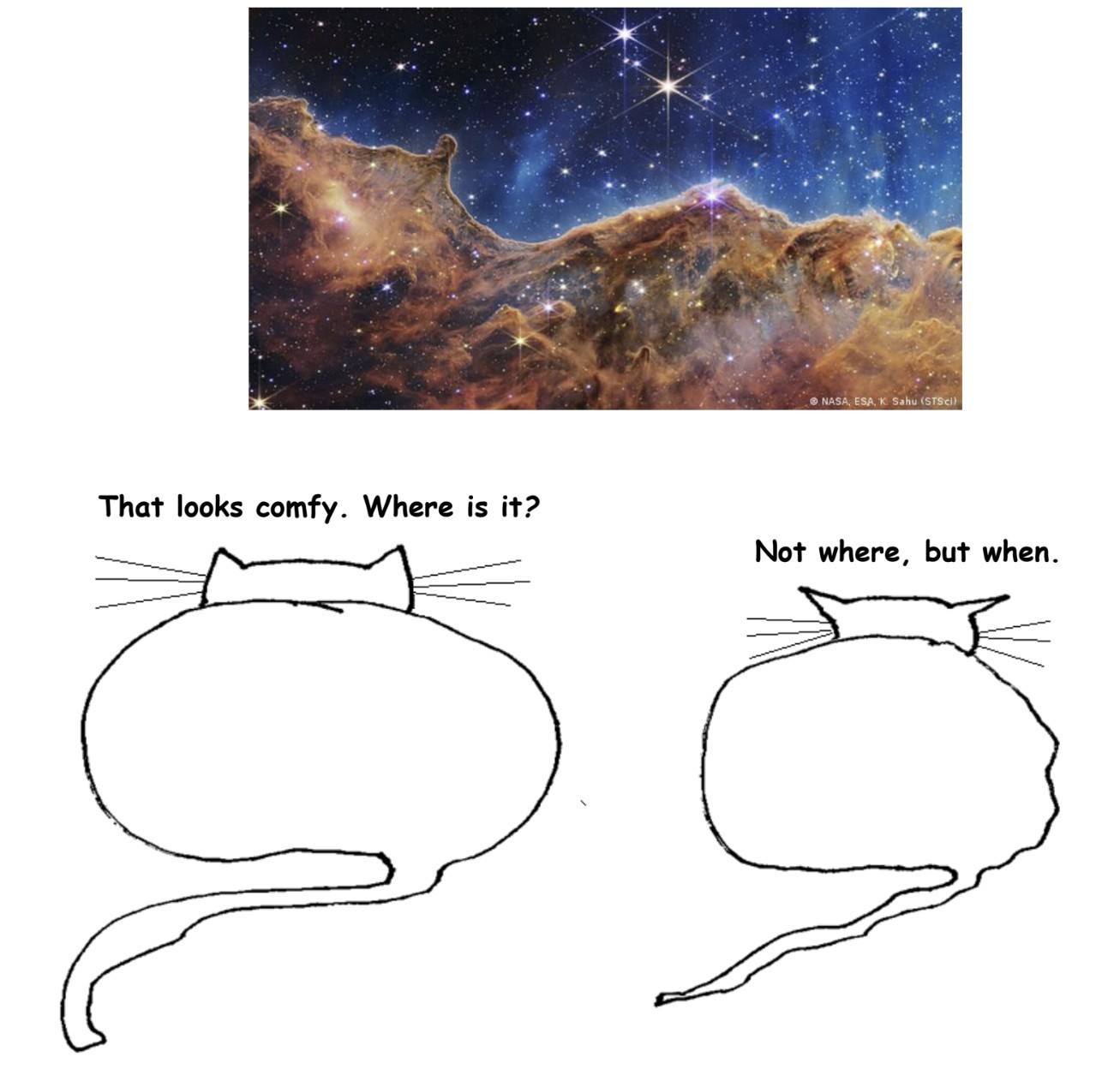

I recently started a new job. The process of looking and interviewing for this job was unlike any other I’ve been through because I now live on the Caribbean island of Grenada. I moved here during the height of the pandemic when everyone was working from home. When I told my plans to the company I was working for then, their only comment was that I needed to stay domiciled in the US, which I have. But now that we’ve all gone back to some kind of post-COVID normalcy (even if variants are still coming at us hard and fast), I wasn’t sure how to approach a new company with my slightly unusual living situation. My initial thoughts were that I get through a first interview before bringing it up, but that seemed not only disingenuous but also pointless; they were going to have a problem with it, or they weren’t. Putting off the reveal was just a waste of everyone’s time. And so, I mostly led with this news. Amazingly, no one cared.

I recently started a new job. The process of looking and interviewing for this job was unlike any other I’ve been through because I now live on the Caribbean island of Grenada. I moved here during the height of the pandemic when everyone was working from home. When I told my plans to the company I was working for then, their only comment was that I needed to stay domiciled in the US, which I have. But now that we’ve all gone back to some kind of post-COVID normalcy (even if variants are still coming at us hard and fast), I wasn’t sure how to approach a new company with my slightly unusual living situation. My initial thoughts were that I get through a first interview before bringing it up, but that seemed not only disingenuous but also pointless; they were going to have a problem with it, or they weren’t. Putting off the reveal was just a waste of everyone’s time. And so, I mostly led with this news. Amazingly, no one cared.  In the early 1990’s I was a visiting fellow at St Catherine’s College and an academic visitor at Nuffield College in Oxford. At Nuffield College at that time two friends from my Cambridge student days were Fellows, Jim Mirrlees and Christopher Bliss. (I think Jim was mostly away during my visit, and graciously asked me to use his large office at Nuffield). The other person I used to see there off and on was Tony Atkinson who became the Warden of Nuffield shortly afterward. I knew Tony since our student days in Cambridge. Like me he also moved from one Cambridge to the other, to MIT, roughly around the same time. Both of us were heavily influenced by our teacher James Meade, though Tony never did a Ph.D. (as used to be the old British tradition—neither James Meade nor Joan Robinson had a Ph.D.) Tony did not follow Meade in the latter’s work on international trade, as I did, but in other respects he broadly followed on the footsteps of Meade, apart from sharing Meade’s personal characteristics of modesty, decency and a positive vision of the future. Tony was certainly among the best economists of my generation, with pioneering work on inequality, poverty, public policies, redistributive taxation, and welfare. He was also an advocate of Universal Basic Income. I had co-authored a chapter for the Handbook of Income Distribution that he co-edited with François Bourguignon, a French development economist friend of mine.

In the early 1990’s I was a visiting fellow at St Catherine’s College and an academic visitor at Nuffield College in Oxford. At Nuffield College at that time two friends from my Cambridge student days were Fellows, Jim Mirrlees and Christopher Bliss. (I think Jim was mostly away during my visit, and graciously asked me to use his large office at Nuffield). The other person I used to see there off and on was Tony Atkinson who became the Warden of Nuffield shortly afterward. I knew Tony since our student days in Cambridge. Like me he also moved from one Cambridge to the other, to MIT, roughly around the same time. Both of us were heavily influenced by our teacher James Meade, though Tony never did a Ph.D. (as used to be the old British tradition—neither James Meade nor Joan Robinson had a Ph.D.) Tony did not follow Meade in the latter’s work on international trade, as I did, but in other respects he broadly followed on the footsteps of Meade, apart from sharing Meade’s personal characteristics of modesty, decency and a positive vision of the future. Tony was certainly among the best economists of my generation, with pioneering work on inequality, poverty, public policies, redistributive taxation, and welfare. He was also an advocate of Universal Basic Income. I had co-authored a chapter for the Handbook of Income Distribution that he co-edited with François Bourguignon, a French development economist friend of mine.

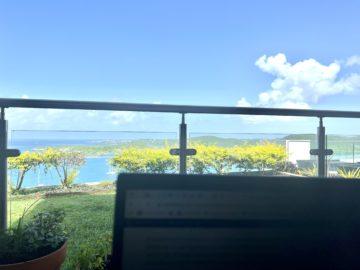

Habiballah of Sava. Concourse of The Birds, ca. 1600

Habiballah of Sava. Concourse of The Birds, ca. 1600

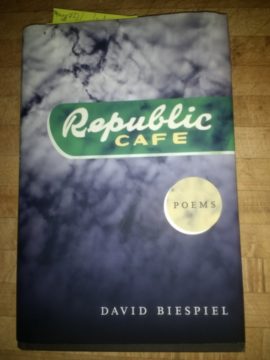

We sit in David Biespiel’s Republic Café: all of us together in the public space of democracy. It appeared in 2019, as American fascism made its perennial strut, less disguised than usual. At that point we’d endured two years of it. Lies spewed from the Leader’s mouth like flies from an open sewer, his followers enacting Hannah Arendt’s crisp formulation:

We sit in David Biespiel’s Republic Café: all of us together in the public space of democracy. It appeared in 2019, as American fascism made its perennial strut, less disguised than usual. At that point we’d endured two years of it. Lies spewed from the Leader’s mouth like flies from an open sewer, his followers enacting Hannah Arendt’s crisp formulation: