by Eric Bies

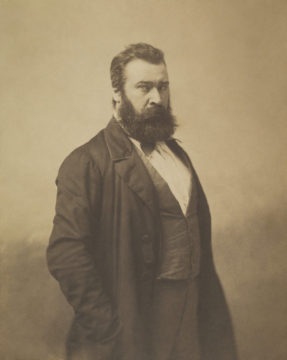

Jean-François Millet, a Frenchman, frowned beneath his full beard as he lay dying in Barbizon. It was 1875, and he was not to be confused with Claude Monet—not yet—who would later paint water lilies and haystacks but wasn’t, in 1875, rich and famous; on the contrary—and in spite of Édouard Manet’s having just painted him painting from the vantage of a covered paddle boat, appearing pretty well-to-do in the process—he was barely getting by. Meanwhile, Millet had already painted some haystacks. And though the stubbier English word his name renovates—the one that rhymes with skillet—happens to be a grain that is rather good for making hay, painters have tended to tend toward other stock. The snow-capped haystacks that we see in Grant Wood, for instance, were in all likelihood made with the same Midwestern alfalfa Verlyn Klinkenborg celebrates and dissects in Making Hay. We know that van Gogh painted a golden haystack or two—probably of wheat—and though the Vermeer Corporation of Pella, Iowa is one of the market leaders in modern hay baling technology, the closest the Dutchman Johannes ever came to a haystack was when he ensconced a common milkmaid in the daylight of a well-windowed kitchen.

Jean-François Millet, a Frenchman, frowned beneath his full beard as he lay dying in Barbizon. It was 1875, and he was not to be confused with Claude Monet—not yet—who would later paint water lilies and haystacks but wasn’t, in 1875, rich and famous; on the contrary—and in spite of Édouard Manet’s having just painted him painting from the vantage of a covered paddle boat, appearing pretty well-to-do in the process—he was barely getting by. Meanwhile, Millet had already painted some haystacks. And though the stubbier English word his name renovates—the one that rhymes with skillet—happens to be a grain that is rather good for making hay, painters have tended to tend toward other stock. The snow-capped haystacks that we see in Grant Wood, for instance, were in all likelihood made with the same Midwestern alfalfa Verlyn Klinkenborg celebrates and dissects in Making Hay. We know that van Gogh painted a golden haystack or two—probably of wheat—and though the Vermeer Corporation of Pella, Iowa is one of the market leaders in modern hay baling technology, the closest the Dutchman Johannes ever came to a haystack was when he ensconced a common milkmaid in the daylight of a well-windowed kitchen.

Whose haystacks won out? It was only a matter of time for Monet. By now his station in the popular imagination has practically eclipsed those of Millet, Wood, and Vermeer, if not van Gogh. We recognize his water lilies as readily as Picasso’s women, Warhol’s soup cans, and, lately, Kusama’s spotted tentacles. It is true that Millet’s Angelus, an apotheosis of peasant soil, shattered art-market records in 1890, exchanging hands Atlanticly for an astonishing 750,000 French francs. Yet the work itself has gradually absconded into what relative obscurity remains feasible for a canvas hanging in the Musée d’Orsay. Read more »

As with game theory, I also attended some courses in Berkeley in another relatively new subject for me, Psychology and Economics (later called Behavioral Economics). In particular I liked the course jointly taught by George Akerlof and Daniel Kahneman (then at Berkeley Psychology Department, later at Princeton). I remember during that time I was once talking to George when my friend and colleague the econometrician Tom Rothenberg came over and asked me to describe in one sentence what I had learned so far from the Akerlof-Kahneman course. I said, somewhat flippantly: “Kahneman is telling us that people are dumber than we economists think, and George is telling us that people are nicer than we economists think”. George liked this description so much that in the next class he started the lecture with my remark. On the dumbness of people I later read somewhere that Kahneman’s earlier fellow-Israeli co-author Amos Tversky once said when asked what he was working on, “My colleagues, they study artificial intelligence; me, I study natural stupidity.”

As with game theory, I also attended some courses in Berkeley in another relatively new subject for me, Psychology and Economics (later called Behavioral Economics). In particular I liked the course jointly taught by George Akerlof and Daniel Kahneman (then at Berkeley Psychology Department, later at Princeton). I remember during that time I was once talking to George when my friend and colleague the econometrician Tom Rothenberg came over and asked me to describe in one sentence what I had learned so far from the Akerlof-Kahneman course. I said, somewhat flippantly: “Kahneman is telling us that people are dumber than we economists think, and George is telling us that people are nicer than we economists think”. George liked this description so much that in the next class he started the lecture with my remark. On the dumbness of people I later read somewhere that Kahneman’s earlier fellow-Israeli co-author Amos Tversky once said when asked what he was working on, “My colleagues, they study artificial intelligence; me, I study natural stupidity.”![Righting America at the Creation Museum (Medicine, Science, and Religion in Historical Context) by [Susan L. Trollinger, William Vance Trollinger]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/511yK1hsSBL.jpg)

Herschel Walker claims that we have enough trees already, that we send China our clean air and they return their dirty air to us, that evolution makes no sense since there are still apes around, and freely offers other astute scientific insights. He may be among the least knowledgeable (to put it mildly) candidates running for office, but he’s not alone and many candidates, I suspect, are also surprisingly innocent of basic math and science. Since innumeracy and science illiteracy remain significant drivers of bad policy decisions, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that congressional candidates (house and senate) be obliged to get a passing grade on a simple quiz.

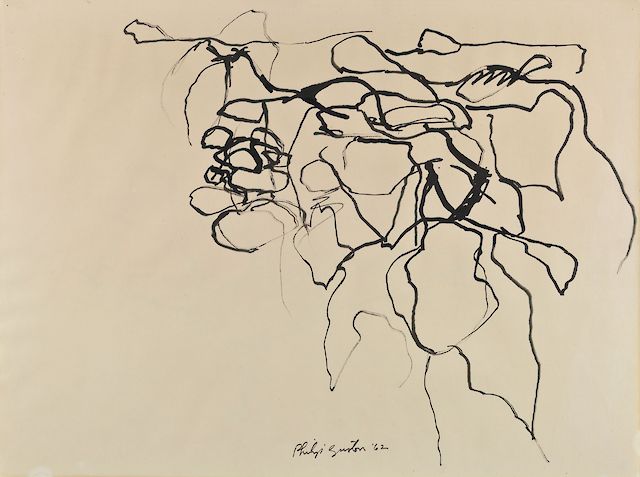

Herschel Walker claims that we have enough trees already, that we send China our clean air and they return their dirty air to us, that evolution makes no sense since there are still apes around, and freely offers other astute scientific insights. He may be among the least knowledgeable (to put it mildly) candidates running for office, but he’s not alone and many candidates, I suspect, are also surprisingly innocent of basic math and science. Since innumeracy and science illiteracy remain significant drivers of bad policy decisions, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that congressional candidates (house and senate) be obliged to get a passing grade on a simple quiz. Philip Guston. Still Life, 1962.

Philip Guston. Still Life, 1962.

I recently listened to a discussion on the topic of

I recently listened to a discussion on the topic of  This summer I noticed that I was sharing a lot of sunset photos on social media. I don’t think of myself as a photographer, and I’m much more likely to share words than images. When I thought about it, I realized this wasn’t a sudden change. I’ve been taking the odd set of sunset pictures with my Canon every now and then, and I’ve noticed that my eyes are increasingly drawn to the sky and the light when I look at landscape photos.

This summer I noticed that I was sharing a lot of sunset photos on social media. I don’t think of myself as a photographer, and I’m much more likely to share words than images. When I thought about it, I realized this wasn’t a sudden change. I’ve been taking the odd set of sunset pictures with my Canon every now and then, and I’ve noticed that my eyes are increasingly drawn to the sky and the light when I look at landscape photos.