by Ashutosh Jogalekar

During a wartime visit to England in early 1943, John von Neumann wrote a letter to his fellow mathematician Oswald Veblen at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, saying:

“I think I have learned a great deal of experimental physics here, particularly of the gas dynamical variety, and that I shall return a better and impurer man. I have also developed an obscene interest in computational techniques…”

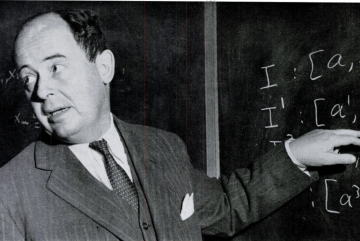

This seemingly mundane communication was to foreshadow a decisive effect on the development of two overwhelmingly important aspects of 20th and 21st century technology – the development of computing and the development of nuclear weapons.

Johnny von Neumann was the multifaceted intellectual diamond of the 20th century. He contributed so many seminal ideas to so many fields so quickly that it would be impossible for any one person to summarize, let alone understand them. He may have been the last universalist in mathematics, having almost complete command of both pure and applied mathematics. But he didn’t stop there. After making fundamental contributions to operator algebra, set theory and the foundations of mathematics, he revolutionized at least two different and disparate fields – economics and computer science – and made contributions to a dozen others, each of which would have been important enough to enshrine his name in scientific history.

But at the end of his relatively short life which was cut down cruelly by cancer, von Neumann had acquired another identity – that of an American patriot who had done more than almost anyone else to make sure that his country was well-defended and ahead of the Soviet Union in the rapidly heating Cold War. Like most other contributions of this sort, this one had a distinctly Faustian gleam to it, bringing both glory and woe to humanity’s experiments in self-elevation and self-destruction. Read more »