by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad

In the last two parts we have discussed encountering the boundary of reason as fracture, and dissolving the boundary altogether. Now we talk about the Islamicate intellectual tradition and how it addresses this threshold. It cultivated a disciplined attentiveness to what appears when knowing falters i.e., a state not of confusion, but of reverent disorientation. In Islamic philosophy and Sufism, the limit of reason is not a catastrophe. It is a disclosure. To reach the boundary of thought is not to exhaust truth. The limit is meant as an opening, it could be outward, inward, upward. Reason could fail but the state of bewilderment that it entails discloses meaning. This orientation reshapes the very role of language, philosophy, and art. No figure articulates this vision more fully than the Spanish Muslim thinker Ibn Arabi. Writing in the thirteenth century, he developed a metaphysics of extraordinary subtlety while insisting, relentlessly, that the Real forever exceeds the structures built to approach it. For Ibn Arabi, reality is not something to be captured but something to be mirrored. The Infinite discloses itself only through finite forms, and those forms are never final. Meaning does not culminate in certainty, it unfolds endlessly through interpretation.

Thus encountering the infinite may lead to paradoxes but they are not meant to be states of failure. Such encounters may even constitute an epistemic virtue! This metaphysics became foundational to Sufism as a lived tradition. Across its many orders and practices e.g., dhikr (remembrance), audition, ethical refinement, disciplined retreat etc the same insight recurs: the self is not annihilated to erase difference, but trained to become permeable. Knowledge is relational. Presence matters more than possession. The limit is not crossed by force, but inhabited with care. In Islamic metaphysics the world is a continuous act of divine self-disclosure (tajalli). Each form is a partial unfolding of an inexhaustible reality. Infinity does not lie beyond the finite; it is enfolded within it. The limit is not where reality ends, but where it becomes legible. Besides Ibn Arabi we see meditations on limits and infinity in the works of thinkers like Suhrawardi’s hierarchies of light to Mulla Ṣadra’s dynamic being, from al-Razi’s interpretive abundance and al-Biruni’s pluralistic cosmology.

Suhrawardi, the 12th century Persian thinker, radicalized the relationship between limit and infinity by reimagining reality itself as a hierarchy of light rather than a collection of substances. In his Illuminationist philosophy (ḥikmat al-ishraq), knowing was not a matter of abstract representation but of increasing luminosity i.e., truth appeared through degrees of intensity rather than conceptual closure. Light enfolded light, each level revealing and concealing the one above it, so that infinity was never reached but continually intimated. The limit, in Suhrawardi’s thought, was perceptual and ethical i.e., one saw only as much as one was prepared to receive. Half a millennium later, Mulla Ṣadra deepened this intuition by arguing that being itself was graded, dynamic, and internally infinite. His doctrine of tashkik al-wujud (the modulation of existence) dissolved any rigid opposition between the finite and the infinite, replacing it with intensification and flow. Reality, for Sadra, was not composed of discrete layers but of continuous variation, endlessly unfolding within itself. Infinity in his metaphysics was not an external beyond but an internal depth that no finite form could exhaust.

Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, the 12th century polymath, articulated one of the most explicit Islamic accounts of meaning as inexhaustible. He embraced interpretive plurality as a structural feature of truth rather than a defect of method. Meaning unfolded through difference and disagreement, each reading illuminating one aspect while leaving others latent. Knowledge, in al-Razi’s work, remained enfolded. Its richness lay precisely in what could not be reduced to a single, definitive articulation. Al-Biruni, writing two centuries before Razi, extended the logic of enfoldment beyond metaphysics into culture and cosmology. His comparative studies of civilizations, sciences, and religions resisted any single explanatory frame, treating plurality as an empirical reality rather than an error to be corrected. Knowledge grew, for al-Biruni, through juxtaposition and co-presence rather than reduction. Infinity appeared in his work not as metaphysical abstraction but as the irreducible richness of the world itself, folded across languages, traditions, and ways of knowing.

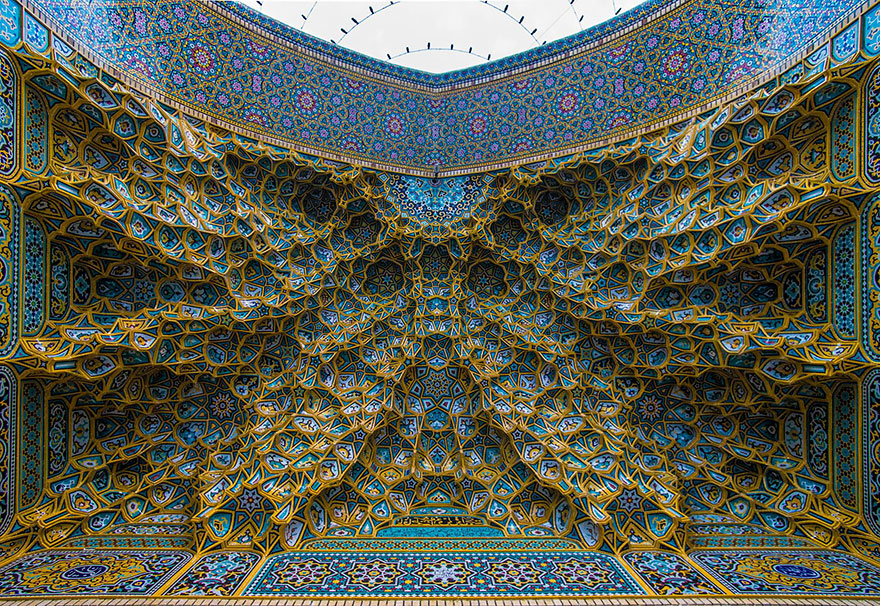

An important text which can help us illuminate this subject is Laura Marks’s Enfoldment and Infinity. Marks posits that Islamic art is fundamentally a negotiation between the Infinite (the divine, the unrepresentable plane of God) and the Limit (the finite, material world). In her framework, the “Infinite” corresponds to Batin (the hidden or implicit), a vast realm of potentiality that is too overwhelming for human perception to grasp directly. To make this meaningful to the viewer, a “limit” must be imposed. This limit is Information or in the context of art, geometry and mathematics. The intricate patterns of Islamic art act as a filter or a screen. They are the “limit” that selects specific aspects of the Infinite and organizes them into a comprehensible, visible form (Zahir). Without the limit of the algorithm or the geometric grid, the Infinite would remain pure, unintelligible chaos. Marks argues that the repeating geometric patterns found in tile work and carpets are visual machines designed to point toward the infinite through the strict application of limits. Unlike Renaissance perspective, which creates an illusion of infinite space extending into the picture plane (a “limit” of the horizon), Islamic art creates an infinite surface. The patterns are recursive and self-similar. they suggest that they could continue expanding forever beyond the physical “limit” of the frame. By rigorously applying finite mathematical rules (algorithms), the artist creates a visual system that mimics the infinite nature of the Divine. The viewer understands that the visible artwork is just a bounded fragment of an infinite, unfolding truth, much like a computer screen displays a limited “view” of a potentially infinite database.

Marks connects the “limit” to the microscopic scale through the concept of Islamic atomism (Kalam theology). This theological school argued that time and space are not continuous but are composed of discrete, indivisible units (atoms) created by God in every instant. Marks draws a direct parallel between this and the pixel i.e., the absolute limit of resolution in digital media. In both Islamic thought and digital logic, the “Infinite” is not a smooth, unbroken flow, but is constructed from a massive accumulation of finite, discrete limits. The digital image and the mosaic tile both acknowledge that reality is granular. Therefore, the “limit” (the pixel, the atom, the tile) is not a barrier to the infinite, but the very building block that allows the infinite to be constructed and enfolded into the world of human perception. Thus the Islamicate engagement with limits does not culminate in mastery, erasure, or silence, but in a sustained practice of attentiveness. To dwell at this threshold was not to linger in uncertainty, but to inhabit an ethical and aesthetic mode of knowing—one that recognized that meaning endured precisely because it could never be exhausted.

I started this series with the aim of doing a trilogy encompassing the Western, Buddhist and Islamic thought. I have decided to expand this project into a four-part series, turning next to Hindu thought, which represents a world in which finitude and infinity are bound together through cosmology, recursion, and eternal return.