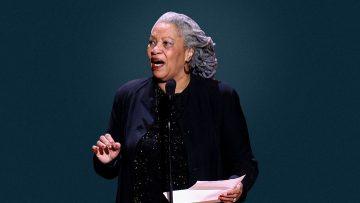

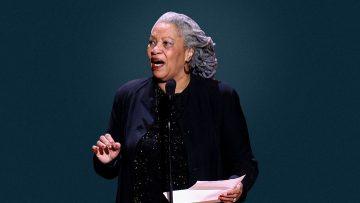

Syreeta McFadden in The Atlantic:

I think a lot about Toni Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Prize lecture. Morrison, who died last week at the age of 88, was one of the nation’s most revered novelists and thinkers, and has left behind an immense opus that has generated renewed interest. Her acceptance speech serves as a prescient reference to the fact that journalists and political leaders today are wrestling with the language necessary to describe the social and political chaos ignited by the Trump administration. It also doubled as a rebuke to detractors flummoxed that Morrison, who wrote inimitable novels about African American life, was being honored with the highest literary prize in the world. In her talk, she invited the audience to engage in an imaginative thought-game, offering a parable of an old blind woman confronted by petulant children. Her speech, though literary and political in nature, outlines the function of language beyond the boundaries of academia and politics.

I think a lot about Toni Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Prize lecture. Morrison, who died last week at the age of 88, was one of the nation’s most revered novelists and thinkers, and has left behind an immense opus that has generated renewed interest. Her acceptance speech serves as a prescient reference to the fact that journalists and political leaders today are wrestling with the language necessary to describe the social and political chaos ignited by the Trump administration. It also doubled as a rebuke to detractors flummoxed that Morrison, who wrote inimitable novels about African American life, was being honored with the highest literary prize in the world. In her talk, she invited the audience to engage in an imaginative thought-game, offering a parable of an old blind woman confronted by petulant children. Her speech, though literary and political in nature, outlines the function of language beyond the boundaries of academia and politics.

The parable begins as such: A group of kids sets out to visit an elderly wise woman, a purported oracle who lives at the edge of town, to prove her powers fraudulent. In Morrison’s retelling, this woman, an American descendant of enslaved black people, attracts these child visitors because “the intelligence of rural prophets is the source of much amusement.” One of the children demands of her: “Old woman, I hold in my hand a bird. Tell me whether it is living or dead.” The old woman, aware of their intent, does not answer, and after a beat she admonishes them for exploiting her blindness—the one difference between them. She tells them that she doesn’t know whether the bird is living or dead, but only that it is in their hands. “Her answer can be taken to mean: If it is dead, you have either found it that way or you have killed it. If it is alive, you can still kill it,” Morrison explained. “Whether it is to stay alive, it is your decision. Whatever the case, it is your responsibility.”

For Morrison, the “bird” was language, and she warned that everyone is culpable for the precarity of language in civil society. “When language dies, out of carelessness, disuse, indifference and absence of esteem, or killed by fiat,” she continued, “not only she herself, but all users and makers are accountable for its demise.” Through this address, Morrison slyly swiped at the national discourse at the time, which focused on how language should be used to define social, cultural, and political realities.

More here.

In the years before Transition House existed, violence at home was considered a private matter between husband and wife. In the early sixties, Janet, an undergraduate at a Seven Sisters college, had just married Jonathan, who was in law school. (Both names are pseudonyms.) Jonathan had started beating her up almost daily; each time, he was filled with remorse, but he blamed Janet for provoking him. Janet had not known any violence growing up, so she found the situation disturbing and bizarre and kept it a secret from most people she knew. She explained her black eyes with the usual stories about bumping into things.

In the years before Transition House existed, violence at home was considered a private matter between husband and wife. In the early sixties, Janet, an undergraduate at a Seven Sisters college, had just married Jonathan, who was in law school. (Both names are pseudonyms.) Jonathan had started beating her up almost daily; each time, he was filled with remorse, but he blamed Janet for provoking him. Janet had not known any violence growing up, so she found the situation disturbing and bizarre and kept it a secret from most people she knew. She explained her black eyes with the usual stories about bumping into things.

We have been friends, Ági and I, since 1969. I was much younger than she, having been born in the last year of the War in 1944. For a moment perhaps, we might have been, my mother and I, and Ági, in one of the same houses of the international ghetto, under Swedish, Swiss or Vatican weak protection. She was 14 or 15 back then, and her dramatic survival — by jumping into the Danube in front of an Arrow Cross Firing squad — has been often recounted.

We have been friends, Ági and I, since 1969. I was much younger than she, having been born in the last year of the War in 1944. For a moment perhaps, we might have been, my mother and I, and Ági, in one of the same houses of the international ghetto, under Swedish, Swiss or Vatican weak protection. She was 14 or 15 back then, and her dramatic survival — by jumping into the Danube in front of an Arrow Cross Firing squad — has been often recounted.  The bloodbath of partition also left the two nations that were borne out of it –

The bloodbath of partition also left the two nations that were borne out of it –  I think a lot about Toni Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Prize lecture. Morrison, who died last week at the age of 88, was one of the nation’s most revered novelists and thinkers, and has left behind an immense opus that has generated renewed interest. Her acceptance

I think a lot about Toni Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Prize lecture. Morrison, who died last week at the age of 88, was one of the nation’s most revered novelists and thinkers, and has left behind an immense opus that has generated renewed interest. Her acceptance  For the first time, researchers have teleported a qutrit, a tripartite unit of quantum information. The independent results from two teams are an important advance for the field of quantum teleportation, which has long been limited to qubits—units of quantum information akin to the binary “bits” used in classical computing. These proof-of-concept experiments demonstrate that qutrits, which can carry more information and have greater resistance to noise than qubits, may be used in future quantum networks. Chinese physicist Guang-Can Guo and his colleagues at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC)

For the first time, researchers have teleported a qutrit, a tripartite unit of quantum information. The independent results from two teams are an important advance for the field of quantum teleportation, which has long been limited to qubits—units of quantum information akin to the binary “bits” used in classical computing. These proof-of-concept experiments demonstrate that qutrits, which can carry more information and have greater resistance to noise than qubits, may be used in future quantum networks. Chinese physicist Guang-Can Guo and his colleagues at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC)  The life of the Polish Jewish author Bruno Schulz was, by pedestrian measures, a small one. It ended prematurely in 1942, when he was murdered in the street at the age of 50 by a Gestapo officer, and it was almost entirely confined to his provincial hometown of Drohobycz. Schulz drew compulsively, and in his brooding sketches crammed big-headed figures into cramped frames and rooms with low, clutching ceilings. Schulz himself was short and hunched. In photographs, he glowers. “He was small, strange, chimerical, focused, intense, almost feverish,” a friend, the Polish novelist Witold Gombrowicz, recalled in a diary entry. His fiction, too, was small and strange. Schulz’s surviving output consists of just two collections of short fiction, some letters, a few essays, and a handful of stray stories. His longest work spans about 150 pages.

The life of the Polish Jewish author Bruno Schulz was, by pedestrian measures, a small one. It ended prematurely in 1942, when he was murdered in the street at the age of 50 by a Gestapo officer, and it was almost entirely confined to his provincial hometown of Drohobycz. Schulz drew compulsively, and in his brooding sketches crammed big-headed figures into cramped frames and rooms with low, clutching ceilings. Schulz himself was short and hunched. In photographs, he glowers. “He was small, strange, chimerical, focused, intense, almost feverish,” a friend, the Polish novelist Witold Gombrowicz, recalled in a diary entry. His fiction, too, was small and strange. Schulz’s surviving output consists of just two collections of short fiction, some letters, a few essays, and a handful of stray stories. His longest work spans about 150 pages. Compared to humans, whales and elephants can have hundreds of times the number of cells — and have similarly long natural lifespans — but their cells mutate, become cancerous, and kill them less frequently. This quirk of nature, which the ACE team is studying, is called Peto’s Paradox, named for

Compared to humans, whales and elephants can have hundreds of times the number of cells — and have similarly long natural lifespans — but their cells mutate, become cancerous, and kill them less frequently. This quirk of nature, which the ACE team is studying, is called Peto’s Paradox, named for  Well, we now have a solid record of what Trump has said and done. And it fits few modern templates exactly. He is no Pinochet nor Hitler, no Nixon nor Clinton. His emergence as a

Well, we now have a solid record of what Trump has said and done. And it fits few modern templates exactly. He is no Pinochet nor Hitler, no Nixon nor Clinton. His emergence as a  The current champion of heavyweight cinema, who vacillates between gallery and traditional cinematic presentation, must be the Chinese documentarian Wang Bing, who broke out internationally with his first film Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2003) and has subsequently produced the fourteen-hour Crude Oil (2008)—premiered as an installation at the 2008 International Film Festival Rotterdam—as well as the nearly nine-hour Dead Souls (2018). Andrew Chan, writing for Film Comment in 2016, distilled the role of duration in Wang’s work, writing, “Wang’s durational extremes do not just carry with them the weight of history and the inertia of the present; they also suggest that we as viewers might repay the gift of his subjects’ nakedness with our own sustained submission.” Chan is writing specifically about Wang’s 2013 ‘Til Madness Do Us Part, a nearly four-hour film that takes place almost entirely inside a dismal, crumbling mental institution doing double-duty as a lock-up for political undesirables. “Time in these films does not embrace, it provokes,” Chan continues, with further reference to West of the Tracks. “It’s felt as sacrifice and labor. And the aim is to make us earn, as if such a thing were possible, the right to lay eyes on humiliations that are at once collectively borne and unbearably private.”

The current champion of heavyweight cinema, who vacillates between gallery and traditional cinematic presentation, must be the Chinese documentarian Wang Bing, who broke out internationally with his first film Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2003) and has subsequently produced the fourteen-hour Crude Oil (2008)—premiered as an installation at the 2008 International Film Festival Rotterdam—as well as the nearly nine-hour Dead Souls (2018). Andrew Chan, writing for Film Comment in 2016, distilled the role of duration in Wang’s work, writing, “Wang’s durational extremes do not just carry with them the weight of history and the inertia of the present; they also suggest that we as viewers might repay the gift of his subjects’ nakedness with our own sustained submission.” Chan is writing specifically about Wang’s 2013 ‘Til Madness Do Us Part, a nearly four-hour film that takes place almost entirely inside a dismal, crumbling mental institution doing double-duty as a lock-up for political undesirables. “Time in these films does not embrace, it provokes,” Chan continues, with further reference to West of the Tracks. “It’s felt as sacrifice and labor. And the aim is to make us earn, as if such a thing were possible, the right to lay eyes on humiliations that are at once collectively borne and unbearably private.”

A Britain without the South Asian British is now almost unthinkable. With a few exceptions – farming, fishing and the armed forces spring to mind – there are few sectors of UK life where the descendants of South Asian immigrants are not prominent. Kavita Puri, for example, author of the harrowing Partition Voices, is a distinguished broadcaster whose father, Ravi, relocated from Delhi to Middlesbrough in 1959. The Puri family had lived originally in Lahore. But while the Puris were Hindu, the majority of Lahoris were Muslim. Under the terms of the 1947 partition plan, Lahore became part of Pakistan. The Puri family, in order to survive the carnage that ensued, had to flee across the border to the new Indian state, ending up in Delhi.

A Britain without the South Asian British is now almost unthinkable. With a few exceptions – farming, fishing and the armed forces spring to mind – there are few sectors of UK life where the descendants of South Asian immigrants are not prominent. Kavita Puri, for example, author of the harrowing Partition Voices, is a distinguished broadcaster whose father, Ravi, relocated from Delhi to Middlesbrough in 1959. The Puri family had lived originally in Lahore. But while the Puris were Hindu, the majority of Lahoris were Muslim. Under the terms of the 1947 partition plan, Lahore became part of Pakistan. The Puri family, in order to survive the carnage that ensued, had to flee across the border to the new Indian state, ending up in Delhi. It matters that the first patients were identical twins. Nancy and Barbara Lowry were six years old, dark-eyed and dark-haired, with eyebrow-skimming bangs. Sometime in the spring of 1960, Nancy fell ill. Her blood counts began to fall; her pediatricians noted that she was anemic. A biopsy revealed that she had a condition called aplastic anemia, a form of bone-marrow failure. The marrow produces blood cells, which need regular replenishing, and Nancy’s was rapidly shutting down. The origins of this illness are often mysterious, but in its typical form the spaces where young blood cells are supposed to be formed gradually fill up with globules of white fat. Barbara, just as mysteriously, was completely healthy. The Lowrys lived in Tacoma, a leafy, rain-slicked city near Seattle. At Seattle’s University of Washington hospital, where Nancy was being treated, the doctors had no clue what to do next. So they called a physician-scientist named E. Donnall Thomas, at the hospital in Cooperstown, New York, asking for help.

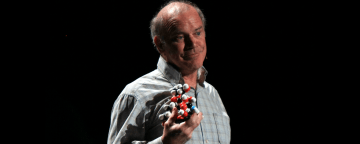

It matters that the first patients were identical twins. Nancy and Barbara Lowry were six years old, dark-eyed and dark-haired, with eyebrow-skimming bangs. Sometime in the spring of 1960, Nancy fell ill. Her blood counts began to fall; her pediatricians noted that she was anemic. A biopsy revealed that she had a condition called aplastic anemia, a form of bone-marrow failure. The marrow produces blood cells, which need regular replenishing, and Nancy’s was rapidly shutting down. The origins of this illness are often mysterious, but in its typical form the spaces where young blood cells are supposed to be formed gradually fill up with globules of white fat. Barbara, just as mysteriously, was completely healthy. The Lowrys lived in Tacoma, a leafy, rain-slicked city near Seattle. At Seattle’s University of Washington hospital, where Nancy was being treated, the doctors had no clue what to do next. So they called a physician-scientist named E. Donnall Thomas, at the hospital in Cooperstown, New York, asking for help. Kary Mullis, whose invention of the polymerase chain reaction technique earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993, died of pneumonia on August 7, according to

Kary Mullis, whose invention of the polymerase chain reaction technique earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993, died of pneumonia on August 7, according to  Climate scientists’ worst-case scenarios back in 2007, the first year the Northwest Passage became navigable without an icebreaker (today, you can book a cruise through it), have all been overtaken by the unforeseen acceleration of events. No one imagined that twelve years later the United Nations would report that we have just twelve years left to avert global catastrophe, which would involve cutting fossil-fuel use nearly by half. Since 2007, the UN now says, we’ve done everything wrong. New coal plants built since the 2015 Paris climate agreement have already doubled the equivalent coal-energy output of Russia and Japan, and 260 more are underway.

Climate scientists’ worst-case scenarios back in 2007, the first year the Northwest Passage became navigable without an icebreaker (today, you can book a cruise through it), have all been overtaken by the unforeseen acceleration of events. No one imagined that twelve years later the United Nations would report that we have just twelve years left to avert global catastrophe, which would involve cutting fossil-fuel use nearly by half. Since 2007, the UN now says, we’ve done everything wrong. New coal plants built since the 2015 Paris climate agreement have already doubled the equivalent coal-energy output of Russia and Japan, and 260 more are underway. The recent revolutions in Algeria and Sudan remind us that bottom-up movements of people power can create sweeping political transformations. They did this in part by mobilizing huge numbers of active protestors—

The recent revolutions in Algeria and Sudan remind us that bottom-up movements of people power can create sweeping political transformations. They did this in part by mobilizing huge numbers of active protestors— The Hindu-supremacist government of

The Hindu-supremacist government of