Kevin Berger in Nautilus:

Helen Clapp, a professor of theoretical physics at MIT, recounted the biggest news of 21st century physics, the detection of gravitational waves by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), an international collaboration of scientists, resulting from the collision of two black holes more than a billion years ago. Einstein posited the existence of gravitational waves in 1915, Clapp said. “People describe these waves as ‘ripples in spacetime,’ with analogies about bowling balls on trampolines and people rolling around on mattresses, and these are probably as good as we’re going to get. The problem with all of the analogies, though, is that they’re three-dimensional; it’s almost impossible for human beings to add a fourth dimension, and visualize how objects with enormous gravity—black holes or dead stars—might bend not only space, but time.”

Helen Clapp, a professor of theoretical physics at MIT, recounted the biggest news of 21st century physics, the detection of gravitational waves by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), an international collaboration of scientists, resulting from the collision of two black holes more than a billion years ago. Einstein posited the existence of gravitational waves in 1915, Clapp said. “People describe these waves as ‘ripples in spacetime,’ with analogies about bowling balls on trampolines and people rolling around on mattresses, and these are probably as good as we’re going to get. The problem with all of the analogies, though, is that they’re three-dimensional; it’s almost impossible for human beings to add a fourth dimension, and visualize how objects with enormous gravity—black holes or dead stars—might bend not only space, but time.”

“Because gravity could stretch matter,” Clapp said, “We knew that a collision between enormously dense objects—black holes or neutron stars—was the most likely way we would be able to hear it. One scientist came up with a good Hollywood analogy—that the universe had finally ‘produced a talkie.’ Actually, the universe has always produced talkies; it was only that we didn’t have the ears to hear them.” The “interferometers became the ears.”

In fact, Clapp is the fictional creation of Nell Freudenberger, the narrator of her recent novel, Lost and Wanted. The novel, Freudenberger’s third, takes readers inside Clapp’s suddenly turbulent world, a single mother whose close friend, Charlie, has died. Freudenberger explored the transformation of characters uprooted from their home countries and cultures in her previous novels, The Dissidentand The Newlyweds, and here traces her physicist’s dislocation as she receives texts from, apparently, her deceased friend, as if she were a ghost.

More here.

Amitava Kumar’s recent novel, Immigrant, Montana, tells the story of Kailash, an Indian graduate student who has immigrated to the US to study at Columbia University, and his education in love as well as in academe. The novel was a New York Times Notable Book of 2018, and it has been compared to the autofiction of Teju Cole and Ben Lerner. In this interview, Kumar talks about how the novel is and is not autobiographical.

Amitava Kumar’s recent novel, Immigrant, Montana, tells the story of Kailash, an Indian graduate student who has immigrated to the US to study at Columbia University, and his education in love as well as in academe. The novel was a New York Times Notable Book of 2018, and it has been compared to the autofiction of Teju Cole and Ben Lerner. In this interview, Kumar talks about how the novel is and is not autobiographical. In 1969, W.H. Auden wrote a skeptical poem about the moon landing after he had declined a request to write a celebratory one.

In 1969, W.H. Auden wrote a skeptical poem about the moon landing after he had declined a request to write a celebratory one. I had just turned twenty-nine and he was forty-eight when we first met out there on City Island, but I quickly realized that he would make a wonderful subject for one of those multi-part profiles the magazine was famous for in those days, and across the next four years, I took on the role of a sort of beanpole Sancho to his capacious Quixote, traipsing about with him on his various rounds and travels, chronicling his in those days floridly neurotic ramblings, indeed, filling up over fifteen notebooks full of them, interviewing his friends and patients and earlier associates, and off to the side, trying to help him through that epic blockage, which, curiously, took the form of graphomania: he’d generated millions of words, just not the right ones, and, for his editors and me, most of the at times Sisyphean work consisted in pruning the damn thing back and then preventing him from mischiefing it yet further.

I had just turned twenty-nine and he was forty-eight when we first met out there on City Island, but I quickly realized that he would make a wonderful subject for one of those multi-part profiles the magazine was famous for in those days, and across the next four years, I took on the role of a sort of beanpole Sancho to his capacious Quixote, traipsing about with him on his various rounds and travels, chronicling his in those days floridly neurotic ramblings, indeed, filling up over fifteen notebooks full of them, interviewing his friends and patients and earlier associates, and off to the side, trying to help him through that epic blockage, which, curiously, took the form of graphomania: he’d generated millions of words, just not the right ones, and, for his editors and me, most of the at times Sisyphean work consisted in pruning the damn thing back and then preventing him from mischiefing it yet further. In the years before Transition House existed, violence at home was considered a private matter between husband and wife. In the early sixties, Janet, an undergraduate at a Seven Sisters college, had just married Jonathan, who was in law school. (Both names are pseudonyms.) Jonathan had started beating her up almost daily; each time, he was filled with remorse, but he blamed Janet for provoking him. Janet had not known any violence growing up, so she found the situation disturbing and bizarre and kept it a secret from most people she knew. She explained her black eyes with the usual stories about bumping into things.

In the years before Transition House existed, violence at home was considered a private matter between husband and wife. In the early sixties, Janet, an undergraduate at a Seven Sisters college, had just married Jonathan, who was in law school. (Both names are pseudonyms.) Jonathan had started beating her up almost daily; each time, he was filled with remorse, but he blamed Janet for provoking him. Janet had not known any violence growing up, so she found the situation disturbing and bizarre and kept it a secret from most people she knew. She explained her black eyes with the usual stories about bumping into things. We have been friends, Ági and I, since 1969. I was much younger than she, having been born in the last year of the War in 1944. For a moment perhaps, we might have been, my mother and I, and Ági, in one of the same houses of the international ghetto, under Swedish, Swiss or Vatican weak protection. She was 14 or 15 back then, and her dramatic survival — by jumping into the Danube in front of an Arrow Cross Firing squad — has been often recounted.

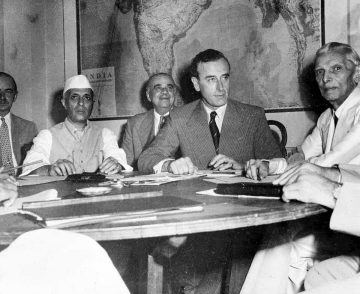

We have been friends, Ági and I, since 1969. I was much younger than she, having been born in the last year of the War in 1944. For a moment perhaps, we might have been, my mother and I, and Ági, in one of the same houses of the international ghetto, under Swedish, Swiss or Vatican weak protection. She was 14 or 15 back then, and her dramatic survival — by jumping into the Danube in front of an Arrow Cross Firing squad — has been often recounted.  The bloodbath of partition also left the two nations that were borne out of it –

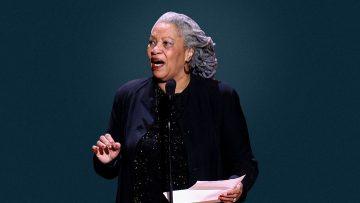

The bloodbath of partition also left the two nations that were borne out of it –  I think a lot about Toni Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Prize lecture. Morrison, who died last week at the age of 88, was one of the nation’s most revered novelists and thinkers, and has left behind an immense opus that has generated renewed interest. Her acceptance

I think a lot about Toni Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Prize lecture. Morrison, who died last week at the age of 88, was one of the nation’s most revered novelists and thinkers, and has left behind an immense opus that has generated renewed interest. Her acceptance  For the first time, researchers have teleported a qutrit, a tripartite unit of quantum information. The independent results from two teams are an important advance for the field of quantum teleportation, which has long been limited to qubits—units of quantum information akin to the binary “bits” used in classical computing. These proof-of-concept experiments demonstrate that qutrits, which can carry more information and have greater resistance to noise than qubits, may be used in future quantum networks. Chinese physicist Guang-Can Guo and his colleagues at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC)

For the first time, researchers have teleported a qutrit, a tripartite unit of quantum information. The independent results from two teams are an important advance for the field of quantum teleportation, which has long been limited to qubits—units of quantum information akin to the binary “bits” used in classical computing. These proof-of-concept experiments demonstrate that qutrits, which can carry more information and have greater resistance to noise than qubits, may be used in future quantum networks. Chinese physicist Guang-Can Guo and his colleagues at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC)  The life of the Polish Jewish author Bruno Schulz was, by pedestrian measures, a small one. It ended prematurely in 1942, when he was murdered in the street at the age of 50 by a Gestapo officer, and it was almost entirely confined to his provincial hometown of Drohobycz. Schulz drew compulsively, and in his brooding sketches crammed big-headed figures into cramped frames and rooms with low, clutching ceilings. Schulz himself was short and hunched. In photographs, he glowers. “He was small, strange, chimerical, focused, intense, almost feverish,” a friend, the Polish novelist Witold Gombrowicz, recalled in a diary entry. His fiction, too, was small and strange. Schulz’s surviving output consists of just two collections of short fiction, some letters, a few essays, and a handful of stray stories. His longest work spans about 150 pages.

The life of the Polish Jewish author Bruno Schulz was, by pedestrian measures, a small one. It ended prematurely in 1942, when he was murdered in the street at the age of 50 by a Gestapo officer, and it was almost entirely confined to his provincial hometown of Drohobycz. Schulz drew compulsively, and in his brooding sketches crammed big-headed figures into cramped frames and rooms with low, clutching ceilings. Schulz himself was short and hunched. In photographs, he glowers. “He was small, strange, chimerical, focused, intense, almost feverish,” a friend, the Polish novelist Witold Gombrowicz, recalled in a diary entry. His fiction, too, was small and strange. Schulz’s surviving output consists of just two collections of short fiction, some letters, a few essays, and a handful of stray stories. His longest work spans about 150 pages. Compared to humans, whales and elephants can have hundreds of times the number of cells — and have similarly long natural lifespans — but their cells mutate, become cancerous, and kill them less frequently. This quirk of nature, which the ACE team is studying, is called Peto’s Paradox, named for

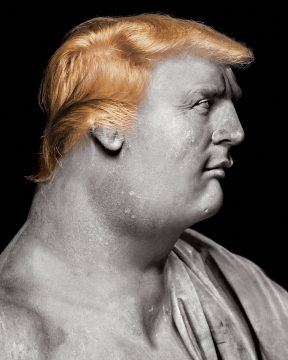

Compared to humans, whales and elephants can have hundreds of times the number of cells — and have similarly long natural lifespans — but their cells mutate, become cancerous, and kill them less frequently. This quirk of nature, which the ACE team is studying, is called Peto’s Paradox, named for  Well, we now have a solid record of what Trump has said and done. And it fits few modern templates exactly. He is no Pinochet nor Hitler, no Nixon nor Clinton. His emergence as a

Well, we now have a solid record of what Trump has said and done. And it fits few modern templates exactly. He is no Pinochet nor Hitler, no Nixon nor Clinton. His emergence as a  The current champion of heavyweight cinema, who vacillates between gallery and traditional cinematic presentation, must be the Chinese documentarian Wang Bing, who broke out internationally with his first film Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2003) and has subsequently produced the fourteen-hour Crude Oil (2008)—premiered as an installation at the 2008 International Film Festival Rotterdam—as well as the nearly nine-hour Dead Souls (2018). Andrew Chan, writing for Film Comment in 2016, distilled the role of duration in Wang’s work, writing, “Wang’s durational extremes do not just carry with them the weight of history and the inertia of the present; they also suggest that we as viewers might repay the gift of his subjects’ nakedness with our own sustained submission.” Chan is writing specifically about Wang’s 2013 ‘Til Madness Do Us Part, a nearly four-hour film that takes place almost entirely inside a dismal, crumbling mental institution doing double-duty as a lock-up for political undesirables. “Time in these films does not embrace, it provokes,” Chan continues, with further reference to West of the Tracks. “It’s felt as sacrifice and labor. And the aim is to make us earn, as if such a thing were possible, the right to lay eyes on humiliations that are at once collectively borne and unbearably private.”

The current champion of heavyweight cinema, who vacillates between gallery and traditional cinematic presentation, must be the Chinese documentarian Wang Bing, who broke out internationally with his first film Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2003) and has subsequently produced the fourteen-hour Crude Oil (2008)—premiered as an installation at the 2008 International Film Festival Rotterdam—as well as the nearly nine-hour Dead Souls (2018). Andrew Chan, writing for Film Comment in 2016, distilled the role of duration in Wang’s work, writing, “Wang’s durational extremes do not just carry with them the weight of history and the inertia of the present; they also suggest that we as viewers might repay the gift of his subjects’ nakedness with our own sustained submission.” Chan is writing specifically about Wang’s 2013 ‘Til Madness Do Us Part, a nearly four-hour film that takes place almost entirely inside a dismal, crumbling mental institution doing double-duty as a lock-up for political undesirables. “Time in these films does not embrace, it provokes,” Chan continues, with further reference to West of the Tracks. “It’s felt as sacrifice and labor. And the aim is to make us earn, as if such a thing were possible, the right to lay eyes on humiliations that are at once collectively borne and unbearably private.”

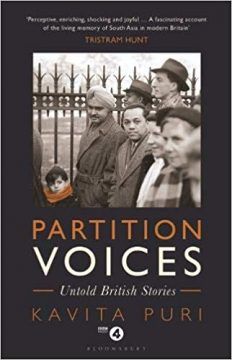

A Britain without the South Asian British is now almost unthinkable. With a few exceptions – farming, fishing and the armed forces spring to mind – there are few sectors of UK life where the descendants of South Asian immigrants are not prominent. Kavita Puri, for example, author of the harrowing Partition Voices, is a distinguished broadcaster whose father, Ravi, relocated from Delhi to Middlesbrough in 1959. The Puri family had lived originally in Lahore. But while the Puris were Hindu, the majority of Lahoris were Muslim. Under the terms of the 1947 partition plan, Lahore became part of Pakistan. The Puri family, in order to survive the carnage that ensued, had to flee across the border to the new Indian state, ending up in Delhi.

A Britain without the South Asian British is now almost unthinkable. With a few exceptions – farming, fishing and the armed forces spring to mind – there are few sectors of UK life where the descendants of South Asian immigrants are not prominent. Kavita Puri, for example, author of the harrowing Partition Voices, is a distinguished broadcaster whose father, Ravi, relocated from Delhi to Middlesbrough in 1959. The Puri family had lived originally in Lahore. But while the Puris were Hindu, the majority of Lahoris were Muslim. Under the terms of the 1947 partition plan, Lahore became part of Pakistan. The Puri family, in order to survive the carnage that ensued, had to flee across the border to the new Indian state, ending up in Delhi. It matters that the first patients were identical twins. Nancy and Barbara Lowry were six years old, dark-eyed and dark-haired, with eyebrow-skimming bangs. Sometime in the spring of 1960, Nancy fell ill. Her blood counts began to fall; her pediatricians noted that she was anemic. A biopsy revealed that she had a condition called aplastic anemia, a form of bone-marrow failure. The marrow produces blood cells, which need regular replenishing, and Nancy’s was rapidly shutting down. The origins of this illness are often mysterious, but in its typical form the spaces where young blood cells are supposed to be formed gradually fill up with globules of white fat. Barbara, just as mysteriously, was completely healthy. The Lowrys lived in Tacoma, a leafy, rain-slicked city near Seattle. At Seattle’s University of Washington hospital, where Nancy was being treated, the doctors had no clue what to do next. So they called a physician-scientist named E. Donnall Thomas, at the hospital in Cooperstown, New York, asking for help.

It matters that the first patients were identical twins. Nancy and Barbara Lowry were six years old, dark-eyed and dark-haired, with eyebrow-skimming bangs. Sometime in the spring of 1960, Nancy fell ill. Her blood counts began to fall; her pediatricians noted that she was anemic. A biopsy revealed that she had a condition called aplastic anemia, a form of bone-marrow failure. The marrow produces blood cells, which need regular replenishing, and Nancy’s was rapidly shutting down. The origins of this illness are often mysterious, but in its typical form the spaces where young blood cells are supposed to be formed gradually fill up with globules of white fat. Barbara, just as mysteriously, was completely healthy. The Lowrys lived in Tacoma, a leafy, rain-slicked city near Seattle. At Seattle’s University of Washington hospital, where Nancy was being treated, the doctors had no clue what to do next. So they called a physician-scientist named E. Donnall Thomas, at the hospital in Cooperstown, New York, asking for help.