Christopher Benfey in the New York Review of Books:

In a glass case at the Musée Rodin, displaying preparatory studies, my attention settled on a terra-cotta fragment identified as “The Thinker’s Right Foot.” His foot! Suddenly, I had a completely different feel for The Thinker. And I found myself wondering whether Rodin, too, had felt that the success of the sculpture might depend in some crucial way on getting the feet right. In one of his two major statements on The Thinker, when he recalled moving from his original concept of Dante in earflaps to something more universal, Rodin wrote: “I conceived another thinker, a naked man; seated upon a rock, his feet drawn under him, his fist against his teeth, he dreams.” The sequence here—the rock, the feet, the fist, the teeth, the dream—implies that thinking, as Rodin conceived of it, emerges from the feet and moves upward and inward. I looked carefully at the Thinker’s right foot, how the big toe slides under the adjacent, sheltering toe to get a better grip.

I half-remembered an essay Georges Bataille wrote on “The Big Toe,” in which he noted that man, “though the most noble of animals… has feet, and these feet independently lead an ignoble life.” Bataille touches here on what one might call the cultural history of feet. Feet are base; they are in touch with dirt, everything that humans, in their vanity, wish to rise above.

More here.

DANIEL ELLSBERG

DANIEL ELLSBERG Noam Chomsky: Trump’s diatribes successfully inflame his audience, many of whom apparently feel deeply threatened by diversity, cultural change, or simply the recognition that the White Christian nation of their collective imagination is changing before their eyes. White supremacy is nothing new in the U.S. The late George Frederickson’s

Noam Chomsky: Trump’s diatribes successfully inflame his audience, many of whom apparently feel deeply threatened by diversity, cultural change, or simply the recognition that the White Christian nation of their collective imagination is changing before their eyes. White supremacy is nothing new in the U.S. The late George Frederickson’s  Born in an Ohio steel town in the depths of the Great Depression, Morrison carved out a literary home for the voices of African Americans, first as an acclaimed editor and then with novels such as The Bluest Eye,

Born in an Ohio steel town in the depths of the Great Depression, Morrison carved out a literary home for the voices of African Americans, first as an acclaimed editor and then with novels such as The Bluest Eye,  ‘We have already exited the state of environmental conditions that allowed the human animal to evolve in the first place,’ Wallace-Wells writes, ‘in an unsure and unplanned bet on just what that animal can endure. The climate system that raised us, and raised everything we now know as human civilisation, is now, like a parent, dead.’ He is not a climate scientist, so is perhaps less circumspect than he might be: the data here is designed to scare us. ‘I am alarmed,’ he writes. Who isn’t? We know exactly where we are, despite the continuous chatter of doubt and denial. Wallace-Wells is scathing about the oil industry, whose disinformation clogs public discourse and waylays political processes: ‘A more grotesque performance of corporate evilness is hardly imaginable, and, a generation from now, oil-backed denial will likely be seen as among the most heinous conspiracies against human health and well-being as have been perpetrated in the modern world.’

‘We have already exited the state of environmental conditions that allowed the human animal to evolve in the first place,’ Wallace-Wells writes, ‘in an unsure and unplanned bet on just what that animal can endure. The climate system that raised us, and raised everything we now know as human civilisation, is now, like a parent, dead.’ He is not a climate scientist, so is perhaps less circumspect than he might be: the data here is designed to scare us. ‘I am alarmed,’ he writes. Who isn’t? We know exactly where we are, despite the continuous chatter of doubt and denial. Wallace-Wells is scathing about the oil industry, whose disinformation clogs public discourse and waylays political processes: ‘A more grotesque performance of corporate evilness is hardly imaginable, and, a generation from now, oil-backed denial will likely be seen as among the most heinous conspiracies against human health and well-being as have been perpetrated in the modern world.’ The laughter of Morrison’s characters disguises pain, deprivation and violation. It is laughter at a series of bad, cruel jokes. The real joke in naming Sula’s neighbourhood “The Bottom”, when it perches on barren Ohio uplands is that, in many senses it really is “the bottom” after all. Nothing is what it seems; no appearance, no relationship, can be trusted to endure.

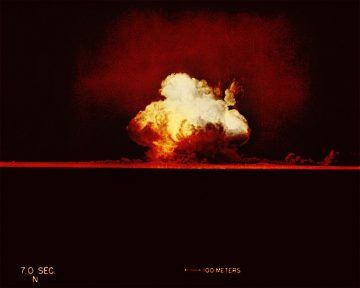

The laughter of Morrison’s characters disguises pain, deprivation and violation. It is laughter at a series of bad, cruel jokes. The real joke in naming Sula’s neighbourhood “The Bottom”, when it perches on barren Ohio uplands is that, in many senses it really is “the bottom” after all. Nothing is what it seems; no appearance, no relationship, can be trusted to endure. Crawford Lake is so small it takes just 10 minutes to stroll all the way around its shore. But beneath its surface, this pond in southern Ontario in Canada hides something special that is attracting attention from scientists around the globe. They are in search of a distinctive marker buried deep in the mud — a signal designating the moment when humans achieved such power that they started irreversibly transforming the planet. The mud layers in this lake could be ground zero for the Anthropocene — a potential new epoch of geological time.

Crawford Lake is so small it takes just 10 minutes to stroll all the way around its shore. But beneath its surface, this pond in southern Ontario in Canada hides something special that is attracting attention from scientists around the globe. They are in search of a distinctive marker buried deep in the mud — a signal designating the moment when humans achieved such power that they started irreversibly transforming the planet. The mud layers in this lake could be ground zero for the Anthropocene — a potential new epoch of geological time. “A lie is a lie is a lie,” Whoopi Goldberg said. It was May 2nd, and she was on the set of “The View,” the daytime talk show that she co-hosts. The subject was Attorney General

“A lie is a lie is a lie,” Whoopi Goldberg said. It was May 2nd, and she was on the set of “The View,” the daytime talk show that she co-hosts. The subject was Attorney General  My colleague Patrick Riley from Google has a

My colleague Patrick Riley from Google has a  One night in May, a strange and seemingly inexplicable thing happened in India. A divisive and ineffectual prime minister returned to power with a historic mandate.

One night in May, a strange and seemingly inexplicable thing happened in India. A divisive and ineffectual prime minister returned to power with a historic mandate. The Cannes Film Festival has been an adoring showcase for Quentin Tarantino ever since he was anointed with the big prize, the Palme d’Or, for Pulp Fiction in 1994. That only made the discomfort of his tense exchange with

The Cannes Film Festival has been an adoring showcase for Quentin Tarantino ever since he was anointed with the big prize, the Palme d’Or, for Pulp Fiction in 1994. That only made the discomfort of his tense exchange with  It took me three tries to understand even a little of Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf’s famous 1925 modernist novel set on a single day in London. Even now, when I try to explain the book, I tend to sound like a stereotypical rambling undergraduate literary analyst, parroting lecture slides and pontificating on the meaning of life — if Good Will Hunting saw me at a bar, he’d take me outside. But confusing as it is, this is a book that makes me walk around differently. Here’s why:

It took me three tries to understand even a little of Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf’s famous 1925 modernist novel set on a single day in London. Even now, when I try to explain the book, I tend to sound like a stereotypical rambling undergraduate literary analyst, parroting lecture slides and pontificating on the meaning of life — if Good Will Hunting saw me at a bar, he’d take me outside. But confusing as it is, this is a book that makes me walk around differently. Here’s why: