James Parker in The Atlantic:

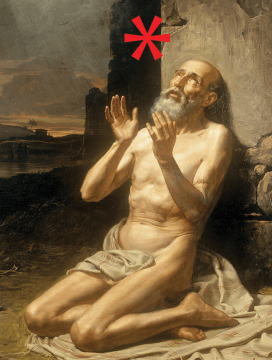

So god says to Satan, “You there, what have you been up to?” And Satan says, “Oh, you know, just hanging around, minding my own business.” And God says, “Well, take a look at my man Job over there. He worships me. He does exactly what I tell him. He thinks I’m the greatest.” “Job?” says Satan. “The rich, happy, healthy guy? The guy with 3,000 camels? Of course he does. You’ve given him everything. Take it all away from him, and I bet you he’ll curse you to your face.” And God says, “You’re on.”

So god says to Satan, “You there, what have you been up to?” And Satan says, “Oh, you know, just hanging around, minding my own business.” And God says, “Well, take a look at my man Job over there. He worships me. He does exactly what I tell him. He thinks I’m the greatest.” “Job?” says Satan. “The rich, happy, healthy guy? The guy with 3,000 camels? Of course he does. You’ve given him everything. Take it all away from him, and I bet you he’ll curse you to your face.” And God says, “You’re on.”

That—give or take a couple of verses—is how it starts, the Book of Job. What a setup. The Trumplike deity; the shrewd and loitering adversary; the cruelly flippant wager; and the stooge, the cosmic straight man, Job, upon whose oblivious head the sky is about to fall. A classic Old Testament skit, pungent as a piece of absurdist theater or a story by Kafka. Job is going to be immiserated, sealed into sorrow—for a bet. What is life? It’s a bleeping and blooping Manichaean casino: You’re up or you’re down, in God’s hands or the devil’s. Piped-in oxygen, controlled light, keep the drinks coming. We, the readers and inheritors of his book, know this. Job, poor bastard, doesn’t.

After his herds have been finished off by marauders and gushes of heavenly fire, and his children have been flattened by falling masonry, and he himself has been covered in running sores from head to toe—after all this happens to the blameless man, he cracks. He sits on an ash heap, seeping and scratching, and reviles the day he was born. “Let that day be darkness,” as the King James Version has it. “Let not God regard it from above, neither let the light shine upon it. Let darkness and the shadow of death stain it; let a cloud dwell upon it; let the blackness of the day terrify it.” Howls of despair are a biblical staple, but Job’s self-curse—the special physics of it, the suicidal pulse that he sends backwards, like a black rainbow, toward the hour of his own conception—is singular. Dispossessed of everything, he is choosing nothing. That first prickle of my existence, the point of light with my name on it? Turn around, All-Fathering One, and eclipse it. Delete.

More here.

Noam Chomsky: The technical work itself is in principle quite separate from personal engagements in other areas. There are no logical connections, though there are some more subtle and historical ones that I’ve occasionally discussed (as have others) and that might be of some significance.

Noam Chomsky: The technical work itself is in principle quite separate from personal engagements in other areas. There are no logical connections, though there are some more subtle and historical ones that I’ve occasionally discussed (as have others) and that might be of some significance. ‘Bunk’ means baloney, hooey, bullshit. Bunk isn’t just a lie, it’s a manipulative lie, the sort of thing a con man might try to get you to believe in order to gain control of your mind and your bank account. Bunk, then, is the tool of social parasites, and the word ‘debunk’ carries with it the expectation of clearing out something that is foreign to the healthy organism. Just as you can deworm a puppy, you can debunk a religious practice, a pyramid scheme, a quack cure. Get rid of the nonsense, and the polity – just like the puppy – will fare better. Con men will be deprived of their innocent marks, and the world will take one more step in the direction of modernity.

‘Bunk’ means baloney, hooey, bullshit. Bunk isn’t just a lie, it’s a manipulative lie, the sort of thing a con man might try to get you to believe in order to gain control of your mind and your bank account. Bunk, then, is the tool of social parasites, and the word ‘debunk’ carries with it the expectation of clearing out something that is foreign to the healthy organism. Just as you can deworm a puppy, you can debunk a religious practice, a pyramid scheme, a quack cure. Get rid of the nonsense, and the polity – just like the puppy – will fare better. Con men will be deprived of their innocent marks, and the world will take one more step in the direction of modernity. Iftikhar was my favourite taxi driver while I lived in London. An elderly Muslim from Lahore, he spoke in lilting, lyrical Punjabi typical of that part of the world. In June 1999, as India and Pakistan fought the Kargil war, he was driving me to Heathrow when the conversation turned to the conflict. I asked what he thought. ‘Doctor sahib‘, he said, ‘when my mother had me, she was suffering from tuberculosis. She was weak and her milk had dried up. Her nextdoor neighbour was a Sikh woman who had also given birth. My mother asked her to breastfeed me. When you ask me about the war, what can I say? I was born of one mother’s womb; another mother suckled me. How can I choose?’

Iftikhar was my favourite taxi driver while I lived in London. An elderly Muslim from Lahore, he spoke in lilting, lyrical Punjabi typical of that part of the world. In June 1999, as India and Pakistan fought the Kargil war, he was driving me to Heathrow when the conversation turned to the conflict. I asked what he thought. ‘Doctor sahib‘, he said, ‘when my mother had me, she was suffering from tuberculosis. She was weak and her milk had dried up. Her nextdoor neighbour was a Sikh woman who had also given birth. My mother asked her to breastfeed me. When you ask me about the war, what can I say? I was born of one mother’s womb; another mother suckled me. How can I choose?’ Tokyo is a city of darkness, a city of light. Each melts into the other. At its center, the city of light blacks out, and at bridges and crossroads, at the margins around train stations, the city of darkness shines, gleaming.

Tokyo is a city of darkness, a city of light. Each melts into the other. At its center, the city of light blacks out, and at bridges and crossroads, at the margins around train stations, the city of darkness shines, gleaming. But how can we think of YHWH as indicating a path away from injustice and oppression? One way we might try to understand Amos’s sense of YHWH in the central passages of the chiasmus is with reference to the notion of wonder. Abraham Joshua Heschel, a prominent twentieth-century theologian, rooted his theology in the teaching of the prophets and particularly in his observation that “to the prophets wonder is a form of thinking … it is an attitude that never ceases.” Importantly, for Heschel, wonder is a real-world experience—one that is latent in every person—resulting from even the most mundane aspects of life. “We do not come upon it only at the climax of thinking or in observing strange, extraordinary facts but in the startling fact that there are facts at all: being, the universe, the unfolding of time,” he writes in God in Search of Man. “We may face it at every turn, in a grain of sand, in an atom, as well as in the stellar space.”

But how can we think of YHWH as indicating a path away from injustice and oppression? One way we might try to understand Amos’s sense of YHWH in the central passages of the chiasmus is with reference to the notion of wonder. Abraham Joshua Heschel, a prominent twentieth-century theologian, rooted his theology in the teaching of the prophets and particularly in his observation that “to the prophets wonder is a form of thinking … it is an attitude that never ceases.” Importantly, for Heschel, wonder is a real-world experience—one that is latent in every person—resulting from even the most mundane aspects of life. “We do not come upon it only at the climax of thinking or in observing strange, extraordinary facts but in the startling fact that there are facts at all: being, the universe, the unfolding of time,” he writes in God in Search of Man. “We may face it at every turn, in a grain of sand, in an atom, as well as in the stellar space.” The Prophecy pictures were made in tragic circumstances. By 1956 Krasner’s marriage to Jackson Pollock was all but broken. In August that year, while Krasner was in Europe, Pollock’s Oldsmobile came off the road at speed, killing himself and Edith Metzger, a friend of his lover, Ruth Kligman. Kligman survived the crash. The paintings Krasner made in response to the horror – and this is almost always her strength – are deeply engaged with other people’s imagery. Fighting with De Kooning’s Woman, as she does throughout – fighting and feeding on his colour, the scale and shape of his Cubist body parts, his bad faith fascination with Marilyn Monroe gorgeousness (bad faith because his irony is so obviously an alibi for gloating) – is her way of discovering what ‘woman’, that terrifying abstraction, meant for her. Out of the engagement comes the originality. Dripping paint, for example, was already a tired Ab Ex trademark by 1956, by no means De Kooning’s exclusive property. But no one had made dripped paint so unlovely, so impatient and passionless, as Krasner did the pinks and whites in Birth. (The tone of the title is undecidable.) For the fight with De Kooning to end in victory, other painters’ weaponry had to be taken out of the closet, some of it distinctly old-fashioned. Krasner was never up to date. Three in Two, for example, evokes explicitly, and not just in its title, the savage Jungian splitting and swapping of genders that Pollock had gone in for a decade earlier, during the time of Two and Male and Female. Behind those paintings lay Picasso, specifically Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Krasner was monstrously confident that she could mobilise this big machinery without in the least repeating its moves – or rather, that she could use the moves to deliver an entirely new, and dreadful, sense of closeness and inhumanity. Embrace, for example, is Les Demoiselles churned into viscera.

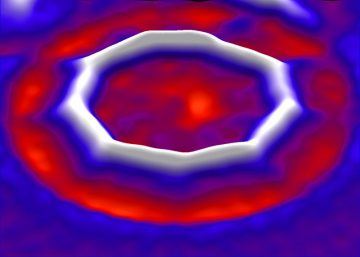

The Prophecy pictures were made in tragic circumstances. By 1956 Krasner’s marriage to Jackson Pollock was all but broken. In August that year, while Krasner was in Europe, Pollock’s Oldsmobile came off the road at speed, killing himself and Edith Metzger, a friend of his lover, Ruth Kligman. Kligman survived the crash. The paintings Krasner made in response to the horror – and this is almost always her strength – are deeply engaged with other people’s imagery. Fighting with De Kooning’s Woman, as she does throughout – fighting and feeding on his colour, the scale and shape of his Cubist body parts, his bad faith fascination with Marilyn Monroe gorgeousness (bad faith because his irony is so obviously an alibi for gloating) – is her way of discovering what ‘woman’, that terrifying abstraction, meant for her. Out of the engagement comes the originality. Dripping paint, for example, was already a tired Ab Ex trademark by 1956, by no means De Kooning’s exclusive property. But no one had made dripped paint so unlovely, so impatient and passionless, as Krasner did the pinks and whites in Birth. (The tone of the title is undecidable.) For the fight with De Kooning to end in victory, other painters’ weaponry had to be taken out of the closet, some of it distinctly old-fashioned. Krasner was never up to date. Three in Two, for example, evokes explicitly, and not just in its title, the savage Jungian splitting and swapping of genders that Pollock had gone in for a decade earlier, during the time of Two and Male and Female. Behind those paintings lay Picasso, specifically Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Krasner was monstrously confident that she could mobilise this big machinery without in the least repeating its moves – or rather, that she could use the moves to deliver an entirely new, and dreadful, sense of closeness and inhumanity. Embrace, for example, is Les Demoiselles churned into viscera. Long after most chemists had given up trying, a team of researchers has synthesized the first ring-shaped molecule of pure carbon — a circle of 18 atoms. The chemists started with a triangular molecule of carbon and oxygen, which they manipulated with electric currents to create the carbon-18 ring. Initial studies of the properties of the molecule, called a cyclocarbon, suggest that it acts as a semiconductor, which could make similar straight carbon chains useful as molecular-scale electronic components. It is an “absolutely stunning work” that opens up a new field of investigation, says Yoshito Tobe, a chemist at Osaka University in Japan. “Many scientists, including myself, have tried to capture cyclocarbons and determine their molecular structures, but in vain,” Tobe says. The results appear in Science

Long after most chemists had given up trying, a team of researchers has synthesized the first ring-shaped molecule of pure carbon — a circle of 18 atoms. The chemists started with a triangular molecule of carbon and oxygen, which they manipulated with electric currents to create the carbon-18 ring. Initial studies of the properties of the molecule, called a cyclocarbon, suggest that it acts as a semiconductor, which could make similar straight carbon chains useful as molecular-scale electronic components. It is an “absolutely stunning work” that opens up a new field of investigation, says Yoshito Tobe, a chemist at Osaka University in Japan. “Many scientists, including myself, have tried to capture cyclocarbons and determine their molecular structures, but in vain,” Tobe says. The results appear in Science

I concur that Trump, as surely as Lee Atwater, marshals racist tropes. But I doubt the last claim: “Instrumental racists” believe that voters will perhaps respond only to racism. And I doubt that voters, in fact, respond only to racism. Something distinct and deeper is at work. This deeper force explains nearly all of Trump’s most odious and irresponsible comments, not just the racist ones. It helps explain why so many conservatives and Republicans were caught off guard by Trump’s rise and the resonance of his bigotry. And it helps clarify what the left sees and doesn’t see about racism. Once leftists understand it, they will find it easier to defeat the identitarian right.

I concur that Trump, as surely as Lee Atwater, marshals racist tropes. But I doubt the last claim: “Instrumental racists” believe that voters will perhaps respond only to racism. And I doubt that voters, in fact, respond only to racism. Something distinct and deeper is at work. This deeper force explains nearly all of Trump’s most odious and irresponsible comments, not just the racist ones. It helps explain why so many conservatives and Republicans were caught off guard by Trump’s rise and the resonance of his bigotry. And it helps clarify what the left sees and doesn’t see about racism. Once leftists understand it, they will find it easier to defeat the identitarian right. There are many mysteries surrounding quantum mechanics. To me, the biggest mysteries are why physicists haven’t yet agreed on a complete understanding of the theory, and even more why they mostly seem content not to try. This puzzling attitude has historical roots that go back to the Bohr-Einstein debates. Adam Becker, in his book What Is Real?, looks at this history, and discusses how physicists have shied away from the foundations of quantum mechanics in the subsequent years. We discuss why this has been the case, and talk about some of the stubborn iconoclasts who insisted on thinking about it anyway.

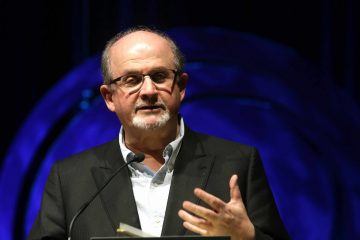

There are many mysteries surrounding quantum mechanics. To me, the biggest mysteries are why physicists haven’t yet agreed on a complete understanding of the theory, and even more why they mostly seem content not to try. This puzzling attitude has historical roots that go back to the Bohr-Einstein debates. Adam Becker, in his book What Is Real?, looks at this history, and discusses how physicists have shied away from the foundations of quantum mechanics in the subsequent years. We discuss why this has been the case, and talk about some of the stubborn iconoclasts who insisted on thinking about it anyway. The novel’s protagonists are Indian-born Muslims. Saladin is a voiceover artist and an immigrant from Bombay to London whose shame about his Indian-ness and desire to be anglicised form the backdrop to a complex interrogation of what it means to be rootless and how migrants in a globalised world can find a sense of identity. Gibreel, meanwhile, is a legend of the Bombay movie scene whose recent health crisis has led him to lose his faith and travel to London to be with the woman he loves, Alleluia Cone. Famous for portraying Hindu gods on screen, Gibreel’s newfound archangelic nature sorely tests his mind—a newly godless man condemned to act as God’s (or is that Satan’s?) right hand on earth.

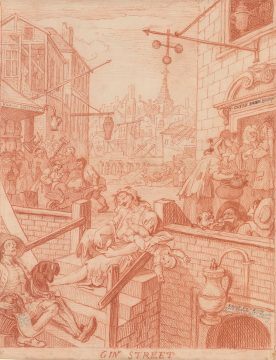

The novel’s protagonists are Indian-born Muslims. Saladin is a voiceover artist and an immigrant from Bombay to London whose shame about his Indian-ness and desire to be anglicised form the backdrop to a complex interrogation of what it means to be rootless and how migrants in a globalised world can find a sense of identity. Gibreel, meanwhile, is a legend of the Bombay movie scene whose recent health crisis has led him to lose his faith and travel to London to be with the woman he loves, Alleluia Cone. Famous for portraying Hindu gods on screen, Gibreel’s newfound archangelic nature sorely tests his mind—a newly godless man condemned to act as God’s (or is that Satan’s?) right hand on earth. “Cruelty and Humor” may be the subtitle of the Hogarth exhibition on display at the Morgan Library through September 22, but “Beer and Gin” would be more fitting. In the early eighteenth century, the British government (amid heightened tensions with France) instituted a policy to promote gin, a traditionally British drink, at the expense of French brandy. The policy proved too effective: by 1743, the average Brit was—in an intoxicated and nationalist frenzy—drinking 2.2 gallons each year. A satirist, agitator, and, in the words of David Bindman, “self-consciously English artist,” William Hogarth (1697–1764) employed his work in the hopes of chilling the “Gin Craze” of the 1750s.

“Cruelty and Humor” may be the subtitle of the Hogarth exhibition on display at the Morgan Library through September 22, but “Beer and Gin” would be more fitting. In the early eighteenth century, the British government (amid heightened tensions with France) instituted a policy to promote gin, a traditionally British drink, at the expense of French brandy. The policy proved too effective: by 1743, the average Brit was—in an intoxicated and nationalist frenzy—drinking 2.2 gallons each year. A satirist, agitator, and, in the words of David Bindman, “self-consciously English artist,” William Hogarth (1697–1764) employed his work in the hopes of chilling the “Gin Craze” of the 1750s. The notion of Anne Frank’s diary as a source of redemption, or at least consolation, received a further boost from the American stage play, written by two Hollywood screenwriters, Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, in 1955. The famous last words in the play are taken from a diary entry on July 15, 1944: “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart”. Thus, the story that would end in Anne’s squalid death was given an uplifting Hollywood ending.

The notion of Anne Frank’s diary as a source of redemption, or at least consolation, received a further boost from the American stage play, written by two Hollywood screenwriters, Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, in 1955. The famous last words in the play are taken from a diary entry on July 15, 1944: “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart”. Thus, the story that would end in Anne’s squalid death was given an uplifting Hollywood ending. We called it El Lago. The Lake. As kids, growing up in the Guatemala of the 1970s, we probably never even knew its name—Lake Amatitlán. Nor did we care. It was only a winding, half-hour drive from the city to my grandparent’s vacation chalet on its shore. We spent most weekends and holidays of my childhood there, jumping off the wooden dock, learning to swim in the icy blue water, digging out old Mayan pots and relics from the muddy bottom, paddling out on long surfboards while little black fish jumped up through the surface and sometimes even landed on the acrylic board. Gently, we’d nudge them back in.

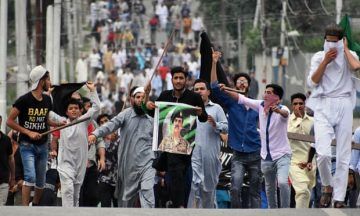

We called it El Lago. The Lake. As kids, growing up in the Guatemala of the 1970s, we probably never even knew its name—Lake Amatitlán. Nor did we care. It was only a winding, half-hour drive from the city to my grandparent’s vacation chalet on its shore. We spent most weekends and holidays of my childhood there, jumping off the wooden dock, learning to swim in the icy blue water, digging out old Mayan pots and relics from the muddy bottom, paddling out on long surfboards while little black fish jumped up through the surface and sometimes even landed on the acrylic board. Gently, we’d nudge them back in. Seventy years after partition, the annexation of Kashmir by India is the endgame of Devraj, the Hindu nationalist businessman protagonist of my 2017 novel

Seventy years after partition, the annexation of Kashmir by India is the endgame of Devraj, the Hindu nationalist businessman protagonist of my 2017 novel