Benjamin Hein in Taxis:

Thousands of years ago, hunters tossed aside their spears and began cultivating the fruits of the earth. The arrival of agricultural society, we have long been told, marked a turning point in human history. Cultivating grains generated an abundance of food, liberating our species from its struggle with scarcity and its primitive, nomadic existence. In the first great bread basket societies such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Rome, humanity flourished. Well-fed and secure, we began devoting ourselves to the finer things in life, like building pyramids and exploring the universe.

Thousands of years ago, hunters tossed aside their spears and began cultivating the fruits of the earth. The arrival of agricultural society, we have long been told, marked a turning point in human history. Cultivating grains generated an abundance of food, liberating our species from its struggle with scarcity and its primitive, nomadic existence. In the first great bread basket societies such as Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Rome, humanity flourished. Well-fed and secure, we began devoting ourselves to the finer things in life, like building pyramids and exploring the universe.

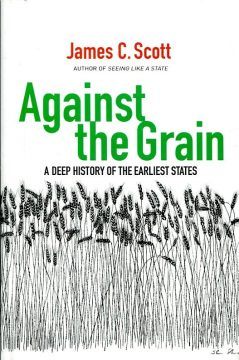

That is an inspiring story about human progress, but also wrong in many ways, argues Yale political scientist James Scott in his latest book Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. Contrary to popular belief, nomadism actually persisted for millennia and indeed predominated as the leading form of social organization for most of human history. Only around 1600 CE did grain-based sedentism begin to supersede nomadic forms of subsistence around the world. One of the reasons why this has been forgotten is our skewed reading of the source record. “If you built, monumentally, in stone and left your debris conveniently in a single place, you were likely to be ‘discovered’ and to dominate the pages of ancient history,” writes Scott. But “if you were hunter-gatherers or nomads, however numerous, spreading your biodegradable trash thinly across the landscape, you were likely to vanish entirely from the archaeological record.”

Another, perhaps more important, problem with the grain narrative is that it relies on a misleading assumption about human nature: that homo sapiens supposedly wishes nothing more in life than to settle down and munch on bread, couscous, or rice. Scott begs to differ.

More here.

Adam Shatz in The New Yorker:

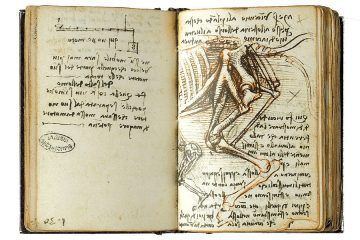

Adam Shatz in The New Yorker: As someone who appreciates Leonardo da Vinci’s painting skills, I’ve long marveled at how crowds rush past his most sublime painting, “The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne,” to line up in front of the “Mona Lisa” at the Louvre Museum in Paris. The art critic in me wants to say, “Wait! Look at this one. See the poses of entwining bodies and gazes, the melting regard of the mother for her child, the translucent folds of cloth, the baby’s chubby legs.” It’s a perfect combination of humanity and divinity. Now, at the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death, scholars, art lovers, and the public are taking a far-reaching look at his career. Exhibitions in Italy and England, as well as the largest-ever survey of his work that opens at the Louvre this fall, are celebrating the master’s achievements not only in art but also in science.

As someone who appreciates Leonardo da Vinci’s painting skills, I’ve long marveled at how crowds rush past his most sublime painting, “The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne,” to line up in front of the “Mona Lisa” at the Louvre Museum in Paris. The art critic in me wants to say, “Wait! Look at this one. See the poses of entwining bodies and gazes, the melting regard of the mother for her child, the translucent folds of cloth, the baby’s chubby legs.” It’s a perfect combination of humanity and divinity. Now, at the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death, scholars, art lovers, and the public are taking a far-reaching look at his career. Exhibitions in Italy and England, as well as the largest-ever survey of his work that opens at the Louvre this fall, are celebrating the master’s achievements not only in art but also in science. The roll of scientists born in the 19th century is as impressive as any century in history. Names such as Albert Einstein, Nikola Tesla, George Washington Carver, Alfred North Whitehead, Louis Agassiz, Benjamin Peirce, Leo Szilard, Edwin Hubble, Katharine Blodgett, Thomas Edison, Gerty Cori, Maria Mitchell, Annie Jump Cannon and Norbert Wiener created a legacy of knowledge and scientific method that fuels our modern lives. Which of these, though, was ‘the best’? Remarkably, in the brilliant light of these names, there was in fact a scientist who surpassed all others in sheer intellectual virtuosity. Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914), pronounced ‘purse’, was a solitary eccentric working in the town of Milford, Pennsylvania, isolated from any intellectual centre. Although many of his contemporaries shared the view that Peirce was a genius of historic proportions, he is little-known today. His current obscurity belies the prediction of the German mathematician Ernst Schröder, who said that Peirce’s ‘fame [will] shine like that of Leibniz or Aristotle into all the thousands of years to come’.

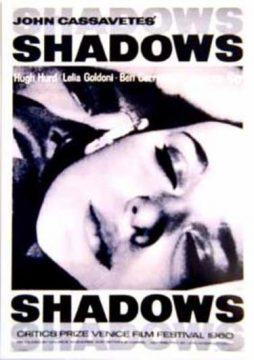

The roll of scientists born in the 19th century is as impressive as any century in history. Names such as Albert Einstein, Nikola Tesla, George Washington Carver, Alfred North Whitehead, Louis Agassiz, Benjamin Peirce, Leo Szilard, Edwin Hubble, Katharine Blodgett, Thomas Edison, Gerty Cori, Maria Mitchell, Annie Jump Cannon and Norbert Wiener created a legacy of knowledge and scientific method that fuels our modern lives. Which of these, though, was ‘the best’? Remarkably, in the brilliant light of these names, there was in fact a scientist who surpassed all others in sheer intellectual virtuosity. Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914), pronounced ‘purse’, was a solitary eccentric working in the town of Milford, Pennsylvania, isolated from any intellectual centre. Although many of his contemporaries shared the view that Peirce was a genius of historic proportions, he is little-known today. His current obscurity belies the prediction of the German mathematician Ernst Schröder, who said that Peirce’s ‘fame [will] shine like that of Leibniz or Aristotle into all the thousands of years to come’. Cassavetes felt galvanized by the looseness and freedom he (mis)read into jazz, which enabled him to make a film with little knowledge or money. At the very least, he shared one quality with Mingus — an ability to bully the people he worked with into doing what he wanted them to do. In a functional sense, both the radical filmmaker and the radical jazz composer were as domineering and rigid as the mainstream structures they railed against.

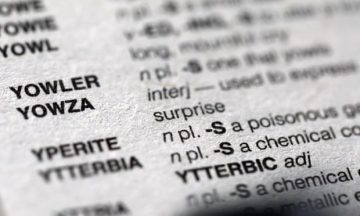

Cassavetes felt galvanized by the looseness and freedom he (mis)read into jazz, which enabled him to make a film with little knowledge or money. At the very least, he shared one quality with Mingus — an ability to bully the people he worked with into doing what he wanted them to do. In a functional sense, both the radical filmmaker and the radical jazz composer were as domineering and rigid as the mainstream structures they railed against. Each chapter explodes a common myth about language. Shariatmadari begins with the most common myth: that standards of English are declining. This is a centuries-old lament for which, he points out, there has never been any evidence. Older people buy into the myth because young people, who are more mobile and have wider social networks, are innovators in language as in other walks of life. Their habit of saying “aks” instead of “ask”, for instance, is a perfectly respectable example of metathesis, a natural linguistic process where the sounds in words swap round. (The word “wasp” used to be “waps” and “horse” used to be “hros”.) Youth is the driver of linguistic change. This means that older people feel linguistic alienation even as they control the institutions – universities, publishers, newspapers, broadcasters – that define standard English.

Each chapter explodes a common myth about language. Shariatmadari begins with the most common myth: that standards of English are declining. This is a centuries-old lament for which, he points out, there has never been any evidence. Older people buy into the myth because young people, who are more mobile and have wider social networks, are innovators in language as in other walks of life. Their habit of saying “aks” instead of “ask”, for instance, is a perfectly respectable example of metathesis, a natural linguistic process where the sounds in words swap round. (The word “wasp” used to be “waps” and “horse” used to be “hros”.) Youth is the driver of linguistic change. This means that older people feel linguistic alienation even as they control the institutions – universities, publishers, newspapers, broadcasters – that define standard English. Katia Moskvitch in Quanta:

Katia Moskvitch in Quanta: Thomas Meaney in The American Historical Review:

Thomas Meaney in The American Historical Review: Quinn Slobodian and William Callison in Dissent:

Quinn Slobodian and William Callison in Dissent: Nikole Hannah-Jones in the NYT:

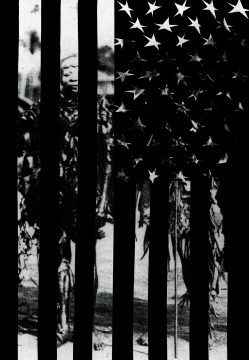

Nikole Hannah-Jones in the NYT: One of the occupational and intellectual hazards of being a historian is that current events often seem far less new to oneself than they do to others. Recently a leftish liberal friend told me that the United States under the Donald Trump had “become a lethal society.” My friend cited the neofascist Trump’s: horrible family separations and concentration camps on the border; openly white-nationalist assaults on four progressive nonwhite and female Congresswomen; real and threatened roundups of undocumented immigrants; fascist-style and hate-filled “Make America Great Again” rallies; encouragement of white supremacist terrorism; alliance with right-wing evangelical Christian fascists.

One of the occupational and intellectual hazards of being a historian is that current events often seem far less new to oneself than they do to others. Recently a leftish liberal friend told me that the United States under the Donald Trump had “become a lethal society.” My friend cited the neofascist Trump’s: horrible family separations and concentration camps on the border; openly white-nationalist assaults on four progressive nonwhite and female Congresswomen; real and threatened roundups of undocumented immigrants; fascist-style and hate-filled “Make America Great Again” rallies; encouragement of white supremacist terrorism; alliance with right-wing evangelical Christian fascists. So god says

So god says  Noam Chomsky: The technical work itself is in principle quite separate from personal engagements in other areas. There are no logical connections, though there are some more subtle and historical ones that I’ve occasionally discussed (as have others) and that might be of some significance.

Noam Chomsky: The technical work itself is in principle quite separate from personal engagements in other areas. There are no logical connections, though there are some more subtle and historical ones that I’ve occasionally discussed (as have others) and that might be of some significance. ‘Bunk’ means baloney, hooey, bullshit. Bunk isn’t just a lie, it’s a manipulative lie, the sort of thing a con man might try to get you to believe in order to gain control of your mind and your bank account. Bunk, then, is the tool of social parasites, and the word ‘debunk’ carries with it the expectation of clearing out something that is foreign to the healthy organism. Just as you can deworm a puppy, you can debunk a religious practice, a pyramid scheme, a quack cure. Get rid of the nonsense, and the polity – just like the puppy – will fare better. Con men will be deprived of their innocent marks, and the world will take one more step in the direction of modernity.

‘Bunk’ means baloney, hooey, bullshit. Bunk isn’t just a lie, it’s a manipulative lie, the sort of thing a con man might try to get you to believe in order to gain control of your mind and your bank account. Bunk, then, is the tool of social parasites, and the word ‘debunk’ carries with it the expectation of clearing out something that is foreign to the healthy organism. Just as you can deworm a puppy, you can debunk a religious practice, a pyramid scheme, a quack cure. Get rid of the nonsense, and the polity – just like the puppy – will fare better. Con men will be deprived of their innocent marks, and the world will take one more step in the direction of modernity.