David Sessions in The Chronicle Review:

The campus upheavals of the 1960s brought a wave of responses from the professoriate, but one in particular stood out. Written by two economists, James M. Buchanan and Nicos E. Devletoglou, Academia in Anarchy (Basic Books, 1970) opened with a law-and-order quote from Richard Nixon and was dedicated to “the taxpayer.” The authors explained that they wrote with “indignation” after observing the bombing of the UCLA economics department, where Buchanan taught, and the “groveling of the UCLA administrative authorities” to a “handful of revolutionary terrorists.”

The campus upheavals of the 1960s brought a wave of responses from the professoriate, but one in particular stood out. Written by two economists, James M. Buchanan and Nicos E. Devletoglou, Academia in Anarchy (Basic Books, 1970) opened with a law-and-order quote from Richard Nixon and was dedicated to “the taxpayer.” The authors explained that they wrote with “indignation” after observing the bombing of the UCLA economics department, where Buchanan taught, and the “groveling of the UCLA administrative authorities” to a “handful of revolutionary terrorists.”

Buchanan and Devletoglou suggested an overhaul of higher education aimed at bringing the student movement to heel. At the time, California had proposed a master plan of universal free higher education across its system. But the authors of Academia in Anarchy argued that the proposal suffered from a lack of basic economics — meaning not simply economic calculation, but Buchanan’s conception of economics as an all-encompassing moral and behavioral philosophy. “Almost alone among social scientists,” they wrote, “the economist brings with him a model of human behavior which allows predictions about human action.”

More here.

Nowadays, not many philosophers are prominent enough to get nicknames. In medieval times the practice was more popular. Every scholastic worth their salt had one: Bonaventure was the “seraphic doctor”, Aquinas the “angelic doctor”, Duns Scotus the “subtle doctor”, and so on. In the Islamic world, too, outstanding thinkers were honoured with such titles. Of these, none was more appropriate than al-shaykh al-raʾīs, which one might loosely translate as “the leading sage”. It was bestowed on Abū ʿAlī Ibn Sīnā (d.1037 AD), who was known to all those medieval scholastics by the Latinized name “Avicenna”. And not just known, but renowned. Avicenna is one of the few philosophers to have become a major influence on the development of a completely foreign philosophical culture. Once his works were translated into Latin he became second only to Aristotle as an inspiration for thirteenth-century medieval philosophy, and (thanks to his definitive medical summary the Canon, in Arabic Qānūn) second only to Galen as a source for medical knowledge in Europe.

Nowadays, not many philosophers are prominent enough to get nicknames. In medieval times the practice was more popular. Every scholastic worth their salt had one: Bonaventure was the “seraphic doctor”, Aquinas the “angelic doctor”, Duns Scotus the “subtle doctor”, and so on. In the Islamic world, too, outstanding thinkers were honoured with such titles. Of these, none was more appropriate than al-shaykh al-raʾīs, which one might loosely translate as “the leading sage”. It was bestowed on Abū ʿAlī Ibn Sīnā (d.1037 AD), who was known to all those medieval scholastics by the Latinized name “Avicenna”. And not just known, but renowned. Avicenna is one of the few philosophers to have become a major influence on the development of a completely foreign philosophical culture. Once his works were translated into Latin he became second only to Aristotle as an inspiration for thirteenth-century medieval philosophy, and (thanks to his definitive medical summary the Canon, in Arabic Qānūn) second only to Galen as a source for medical knowledge in Europe. When Wellcome Sanger Institute geneticist

When Wellcome Sanger Institute geneticist

A

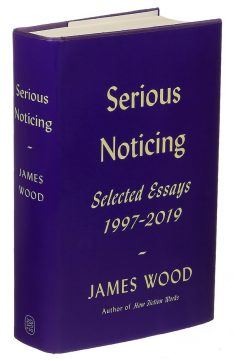

A  In the introduction, Wood mentions that he was taught how to read by a deconstructionist who would badger the class with the same question: “What are the stakes here?” The two voices mingling in this collection give a beautiful, moving sense of the stakes of criticism as Wood has practiced it, vigorously, without interruption for 30 years: What does it mean to do this work well, and what does it add to the world? What has it added to his life? Wood’s latest novel, “Upstate,” which follows a deeply depressed philosopher, dramatizes these questions about the relationships between analysis and fulfillment. He writes in that book: “If intelligent people could think themselves into happiness, intellectuals would be the happiest people on earth.”

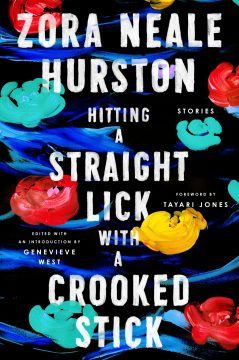

In the introduction, Wood mentions that he was taught how to read by a deconstructionist who would badger the class with the same question: “What are the stakes here?” The two voices mingling in this collection give a beautiful, moving sense of the stakes of criticism as Wood has practiced it, vigorously, without interruption for 30 years: What does it mean to do this work well, and what does it add to the world? What has it added to his life? Wood’s latest novel, “Upstate,” which follows a deeply depressed philosopher, dramatizes these questions about the relationships between analysis and fulfillment. He writes in that book: “If intelligent people could think themselves into happiness, intellectuals would be the happiest people on earth.” Sixty years after Zora Neale Hurston’s death in relative obscurity, a new collection of short fiction by the legendary African American author and anthropologist has arrived. For readers who are more familiar with Hurston’s novels, the collection “

Sixty years after Zora Neale Hurston’s death in relative obscurity, a new collection of short fiction by the legendary African American author and anthropologist has arrived. For readers who are more familiar with Hurston’s novels, the collection “ “Please don’t make me vote for Joe Biden!” a flock of teenagers pleaded in a

“Please don’t make me vote for Joe Biden!” a flock of teenagers pleaded in a  In the middle of September, shortly before the House of Representatives opened its impeachment inquiry against President Trump, I started texting with his personal lawyer, Rudolph Giuliani, to try to arrange a time to get together. I stressed that I wasn’t looking for sound bites; I wanted to talk, in depth, about the whole arc of his career, with the goal of explaining how he wound up at the center of this historic moment. There were several weeks of inconclusive, if at times amusing, exchanges — when I reminded him of the numerous Giuliani profiles this magazine has published over the course of the last four decades, he ‘‘loved’’ my text — before I decided to call him on his cellphone. It was a Friday evening, a few days after his business associates Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman were arraigned on charges of conspiring to funnel foreign money into American elections. To my surprise, Giuliani answered. I could hear that he was in a crowded bar or restaurant; he sounded as if he was in good spirits. ‘‘I really want to talk to you,’’ he said. ‘‘The thing is, I’m a little busy right now. Give me another week, and I should have all of this behind me.’’

In the middle of September, shortly before the House of Representatives opened its impeachment inquiry against President Trump, I started texting with his personal lawyer, Rudolph Giuliani, to try to arrange a time to get together. I stressed that I wasn’t looking for sound bites; I wanted to talk, in depth, about the whole arc of his career, with the goal of explaining how he wound up at the center of this historic moment. There were several weeks of inconclusive, if at times amusing, exchanges — when I reminded him of the numerous Giuliani profiles this magazine has published over the course of the last four decades, he ‘‘loved’’ my text — before I decided to call him on his cellphone. It was a Friday evening, a few days after his business associates Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman were arraigned on charges of conspiring to funnel foreign money into American elections. To my surprise, Giuliani answered. I could hear that he was in a crowded bar or restaurant; he sounded as if he was in good spirits. ‘‘I really want to talk to you,’’ he said. ‘‘The thing is, I’m a little busy right now. Give me another week, and I should have all of this behind me.’’ During schoolyard spats between young boys, conflicts rarely end in punches. There is, instead, a perpetual appeal to those higher up in the food chain—all grade-school boys magically have a big brother who is ready, apparently, to fight someone half their age, or, if necessary, beat up the rival’s hypothetical older brother. Because of an eight-year-old boy’s inability to really hurt anybody, harkening to brothers capable of real violence is a means of confirming one’s own capacity to provoke fear in others.

During schoolyard spats between young boys, conflicts rarely end in punches. There is, instead, a perpetual appeal to those higher up in the food chain—all grade-school boys magically have a big brother who is ready, apparently, to fight someone half their age, or, if necessary, beat up the rival’s hypothetical older brother. Because of an eight-year-old boy’s inability to really hurt anybody, harkening to brothers capable of real violence is a means of confirming one’s own capacity to provoke fear in others.

There has never been more anxiety about the effects of our love of screens — which now bombard us with social-media updates, news (real and fake), advertising and blue-spectrum light that could disrupt our sleep. Concerns are growing about impacts on mental and physical health, education, relationships, even on politics and democracy. Just last year, the World Health Organization issued new guidelines about limiting children’s screen time; the US Congress investigated the influence of social media on political bias and voting; and California introduced a law (Assembly Bill 272) that allows schools to restrict pupils’ use of smartphones.

There has never been more anxiety about the effects of our love of screens — which now bombard us with social-media updates, news (real and fake), advertising and blue-spectrum light that could disrupt our sleep. Concerns are growing about impacts on mental and physical health, education, relationships, even on politics and democracy. Just last year, the World Health Organization issued new guidelines about limiting children’s screen time; the US Congress investigated the influence of social media on political bias and voting; and California introduced a law (Assembly Bill 272) that allows schools to restrict pupils’ use of smartphones.