Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

John Berger and Michael Silverblatt

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Iran: An Explosion Long in the Making

Arang Keshavarzian at Equator:

The comparison with 1979 is lazy because it assumes that history is a model that repeats itself in exactly the same way. So when the bazaaris protested and closed their shops in late December, many “Iran-watchers” perked up, suggesting that this moment would result in an overthrow of the state. In fact, whenever there’s turmoil in Iran people reach for the 1979 analogy, a move that narrows our political imagination and stunts our analytical capacities.

The comparison with 1979 is lazy because it assumes that history is a model that repeats itself in exactly the same way. So when the bazaaris protested and closed their shops in late December, many “Iran-watchers” perked up, suggesting that this moment would result in an overthrow of the state. In fact, whenever there’s turmoil in Iran people reach for the 1979 analogy, a move that narrows our political imagination and stunts our analytical capacities.

1979 can offer some rough general threads to look for. We can ask: Are there cross-class coalitions being forged? Do these coalitions weaken the ability of the state to function? For instance, in 1978, labor strikes in the oil fields and in bureaucracies not only mobilized people, but also reduced the capacity of the monarchy to rely on a functioning state. This hasn’t happened today. The state is still intact. We‘re far from a revolutionary situation.

There are other differences between then and now.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

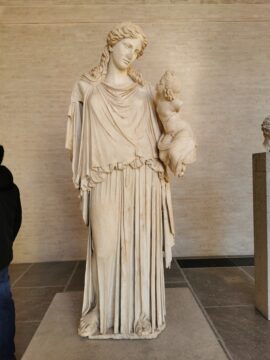

Ancient Athens Created a Goddess

Anna Gustafsson at JSTOR Daily:

The Peloponnesian War ended in 404 BCE with Athens’s devastating loss. Its once heralded naval fleet was largely destroyed. Plague and defeat on the battlefield had killed more than a quarter of its people. Conflicts and epidemics had left the Athenian economy in shambles. Restoring prosperity required lasting peace, but asking the proud Athenians to lay down swords after humiliation was a political gamble. They needed a more straightforward approach to ending aggression.

The Peloponnesian War ended in 404 BCE with Athens’s devastating loss. Its once heralded naval fleet was largely destroyed. Plague and defeat on the battlefield had killed more than a quarter of its people. Conflicts and epidemics had left the Athenian economy in shambles. Restoring prosperity required lasting peace, but asking the proud Athenians to lay down swords after humiliation was a political gamble. They needed a more straightforward approach to ending aggression.

After decades of war, the Athenians decided peace would no longer be an abstraction. Instead, it would be personified as a deity, the goddess Eirene, and worshipped as such. To be clear, religion in ancient Greece was not “faith” in the way we understand it today. It did not necessarily guide individual’s private thoughts or provide a moral compass. Instead, it was deeply embedded in public life. Practicing religion was a social and civic duty, aimed at maintaining harmony between mortals and the divine. Religious acts such as prayers, libations, and dedication of votive offerings were typically performed at public shrines and altars. These were visible, communal gestures, often tied to festivals, civic events, or transitions in life, such as marriage, war, or death.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

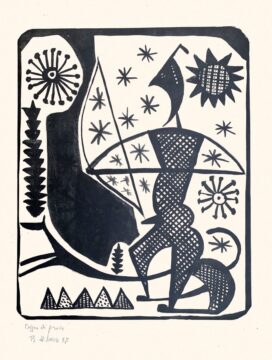

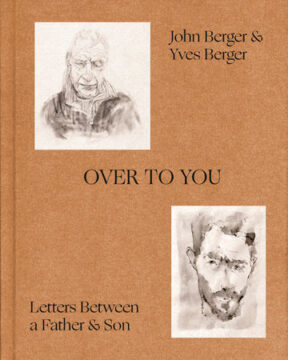

John and Yves Berger’s Letters on the Nature of Art

Olga Zolotareva at The Millions:

Halfway through Over to You, the painter Yves Berger recounts a meeting with university students interested in his creative process. The meeting, he feels, was a “failure,” in part because of the inadequacy of his visual aid—photographs of three of his works in various stages of completion. The photographs “gave the impression of a linear process, as if Time were an arrow, whereas the real experience we have of it is made of folds, and folds within folds, sometimes touching one another.”

Halfway through Over to You, the painter Yves Berger recounts a meeting with university students interested in his creative process. The meeting, he feels, was a “failure,” in part because of the inadequacy of his visual aid—photographs of three of his works in various stages of completion. The photographs “gave the impression of a linear process, as if Time were an arrow, whereas the real experience we have of it is made of folds, and folds within folds, sometimes touching one another.”

Over to You, a collection of letters exchanged by Yves and his father between 2015 and 2016, the artist and art critic John Berger (1926-2017), comes closer to giving us “the real experience” of time. In its pages, paintings from different historical periods (all helpfully reproduced in color) call out to one another: Albrecht Dürer’s Screech Owl (1508) “wink[s]” at Max Beckmann’s Columbine (1950); Vincent Van Gogh’s Still Life with Bible (1885) responds to Rogier van der Weyden’s The Annunciation (c. 1440); and John Berger’s own watercolor rose nods to Andrea della Robbia’s Madonna with Four Angels (c. 1480-1490). Throughout much of the book, the images are embedded in the letters. But toward the end, the words disappear, giving way to a visual essay—a form that would be familiar to the readers of John Berger’s celebrated 1972 book Ways of Seeing.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

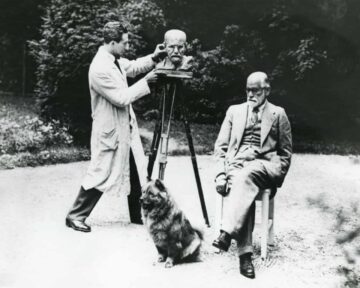

has modern neuroscience proved Freud right?

Raymond Tallis in The Guardian:

Vladimir Nabokov notoriously dismissed the “vulgar, shabby, and fundamentally medieval world” of the ideas of Sigmund Freud, whom he called “the Viennese witch doctor”. His negative judgment has been shared by many in the near 90 years since Freud’s death. A reputational high-water mark in the postwar period was followed by a collapse, at least in scientific circles, but there are signs of newfound respectability for his ideas, including among those who once rejected him outright. Mark Solms’s latest book, a wide-ranging and engrossing defence of Freud as a scientist and a healer, is a striking contribution to the re-evaluation of a thinker whom WH Auden described as “no more a person now but a whole climate of opinion”.

Vladimir Nabokov notoriously dismissed the “vulgar, shabby, and fundamentally medieval world” of the ideas of Sigmund Freud, whom he called “the Viennese witch doctor”. His negative judgment has been shared by many in the near 90 years since Freud’s death. A reputational high-water mark in the postwar period was followed by a collapse, at least in scientific circles, but there are signs of newfound respectability for his ideas, including among those who once rejected him outright. Mark Solms’s latest book, a wide-ranging and engrossing defence of Freud as a scientist and a healer, is a striking contribution to the re-evaluation of a thinker whom WH Auden described as “no more a person now but a whole climate of opinion”.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

I’m a gastroenterologist. Here are some surprising GLP-1 gut benefits

Trisha Parsicha in The Washington Post:

In the original clinical trials of GLP-1 medications for weight loss, the most common side effects were gastrointestinal, including nausea, vomiting and constipation. Ask almost anyone who’s been on one, and they’ll probably tell you that they’ve had some GI issues — even if very mild. So you might be surprised that as a gastroenterologist, when my patients tell me they’re considering starting a GLP-1 (the class of drug that includes Ozempic, Wegovy and Zepbound, among others), my answer is often highly enthusiastic: Do. It.

In the original clinical trials of GLP-1 medications for weight loss, the most common side effects were gastrointestinal, including nausea, vomiting and constipation. Ask almost anyone who’s been on one, and they’ll probably tell you that they’ve had some GI issues — even if very mild. So you might be surprised that as a gastroenterologist, when my patients tell me they’re considering starting a GLP-1 (the class of drug that includes Ozempic, Wegovy and Zepbound, among others), my answer is often highly enthusiastic: Do. It.

We hear all the time about the weight loss or heart health benefits of GLP-1s, but as a scientist who studies GLP-1 and the stomach in my own laboratory, I’ve seen first-hand how powerful and beneficial they can be for gut health. The GI effects of GLP-1s that I wish more people talked about? Randomized controlled trials have found that they can, in some cases, improve outcomes for people with fatty liver disease and fibrosis — or liver scarring — which previously no drugs could reliably achieve.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday, January 18, 2026

The crisis whisperer: how Adam Tooze makes sense of our bewildering age

Robert P Baird in The Guardian:

In late January 2025, 10 days after Donald Trump was sworn in for a second time as president of the United States, an economic conference in Brussels brought together several officials from the recently deposed Biden administration for a discussion about the global economy. In Washington, Trump and his wrecking crew were already busy razing every last brick of Joe Biden’s legacy, but in Brussels, the Democratic exiles put on a brave face. They summoned the comforting ghosts of white papers past, intoning old spells like “worker-centered trade policy” and “middle-out bottom-up economics”. They touted their late-term achievements. They even quoted poetry: “We did not go gently into that good night,” Katherine Tai, who served as Biden’s US trade representative, said from the stage. Tai proudly told the audience that before leaving office she and her team had worked hard to complete “a set of supply-chain-resiliency papers, a set of model negotiating texts, and a shipbuilding investigation”.

It was not until 70 minutes into the conversation that a discordant note was sounded, when Adam Tooze joined the panel remotely. Born in London, raised in West Germany, and living now in New York, where he teaches at Columbia, Tooze was for many years a successful but largely unknown academic. A decade ago he was recognised, when he was recognised at all, as an economic historian of Europe. Since 2018, however, when he published Crashed, his “contemporary history” of the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath, Tooze has become, in the words of Jonathan Derbyshire, his editor at the Financial Times, “a sort of platonic ideal of the universal intellectual”.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

After AI

Cédric Durand in Sidecar:

The stock market valuation of AI-related firms has increased tenfold over the past decade. As John Lanchester noted recently, all but one of the world’s ten largest companies are connected to the future value of artificial intelligence. All but one of those are American, and together their value is equal to well over half of the US economy. Over the past few years, anticipation of the AI ‘revolution’ has driven a surge in investment in these US tech companies. Promises of a radical breakthrough in post-human intelligence and miraculous productivity gains have captured the animal spirits of investors to the point where, as the FT’s Ruchir Sharma put it, ‘America is now one big bet on AI’. Fixed investment in the sector is so enormous that it was the primary driver of US growth in 2025. The training and operation of AI models requires a huge physical build-up of data centres, computing equipment, cooling systems, network hardware, grid connections and power provision. Tech firms are expected to spend a staggering $5 trillion on this costly infrastructure – which is still mostly concentrated in the US – to meet expected demand between now and 2030.

The problem is that the numbers do not add up. To meet its colossal financial needs the sector has shifted from a model dominated by cash-flow and equity financing to debt financing. In principle, this turn to debt could simply reflect growing profit opportunities and the anticipation of forthcoming prosperity. Increasingly exotic financial deals suggest otherwise. A large part of the hype is fuelled by financial loops in which suppliers invest in their clients and vice versa. OpenAI is a case in point. Its leading chip provider, Nvidia – the most valuable company in the world – is planning to invest $100 billion in OpenAI, effectively funding demand for its own products. OpenAI, meanwhile, is spending almost twice what it earns on Microsoft’s cloud platform Azure, which provides the computing power to run its services, thereby enriching its main backer while accumulating debt.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Where a Hundred Analogies Bloom

Christian Sorace in The Ideas Letter:

Current political discourse is haunted by a specter—the specter of Maoism. When conventional politics starts to spin away from the mainstream and arouses the passions of the people, Mao often is invoked. Commentators routinely analogize Trump to him, calling the two men kindred spirits in “chaos” who “would have got on well.” The China expert Orville Schell has written that the Chairman “must be looking down from his Marxist-Leninist heaven with a smile.”

But would Mao really have celebrated anything beyond disorder for the US empire?

Such easy analogies are not only incorrect; worse, they damage our capacity for critical thinking and political action. Relying on them inhibits imagining a democratic politics beyond liberal democracy.

During periods of uncertainty, historical analogies can convey familiarity. But as they do, they distract from what is new in the present. Trump has been compared not only to Mao, but also to Hitler—as well as to contemporaries such as Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, and the dictators of so-called banana republics. As we travel in that time machine, one moment we are in the kinetic interwar years; in the next, we glaciate in a new Cold War. Analogies seem to reassure us that we have been there before. In fact, they only confuse any real sense of where we are now.

Portraits of bad men—master manipulators with a sociopathic disregard for the havoc they wreak on their nations, peoples, and economies—may be accurate characterizations, but they say little about sociopolitical dynamics, which are larger than any personality. They do not make up for proper political analysis. When a leader’s actions are presented out of context, their only imaginable purpose appears to be the consolidation of power—power without politics.

Yet historical analogies themselves are rhetorical devices; they too are tellers and makers of tales, and they create political claims. They implicitly ask us to see the world in a certain way—usually from the perspective of the status quo, from which alternative modes of politics are passed over or pathologized. To compare Trump to Mao and the US culture wars to the Cultural Revolution is to reduce entirely different political visions to reified personalities.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Matrices of Empire

Fernando Rugitsky in Phenomenal World:

After giving the order for Nicolás Maduro’s kidnapping, Donald Trump declared that the United States was now planning to ‘‘run’’ Venezuela. “It won’t cost us anything,” Trump said,

because the money coming out of the ground is very substantial . . . The oil companies are going to go in. They’re going to spend money. We’re going to take back the oil that, frankly, we should have taken back a long time ago. A lot of money is coming out of the ground.

In the past, when Washington claimed to act in the name of humanitarianism, democracy, or freedom, it was up to us—political economists—to reveal its ulterior motives, the material interests beneath the media spin. Now, as TJ Clark has written, political hypocrisy itself seems to be under threat. If imperial resource-grabbing is openly acknowledged, what is left for us to analyze?

Over the last week, much of the debate on the US attack has questioned whether oil is really the determinant factor. Some argue that Venezuela’s heavy crude is too expensive to extract, and that—given the current state of the market and the unlikelihood of price increases in the near future—this would be an irrational investment for US corporations. Others, meanwhile, note that about half of Venezuela’s oil reserves are not of the heavy kind found in the Orinoco Belt, and claim that in oil fields in the Maracaibo and Monagas basins there is still the potential for “quick wins” for big oil companies and oil-service firms.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Rebecca Kilgore (1949 – 2026) Jazz Vocalist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Gabriel Barkay (1944 – 2026) Archaeologist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How can we defend ourselves from the new plague of ‘human fracking’?

From The Guardian:

In the last 15 years, a linked series of unprecedented technologies have changed the experience of personhood across most of the world. It is estimated that nearly 70% of the human population of the Earth currently possesses a smartphone, and these devices constitute about 95% of internet access-points on the planet. Globally, on average, people seem to spend close to half their waking hours looking at screens, and among young people in the rich world the number is a good deal higher than that.

In the last 15 years, a linked series of unprecedented technologies have changed the experience of personhood across most of the world. It is estimated that nearly 70% of the human population of the Earth currently possesses a smartphone, and these devices constitute about 95% of internet access-points on the planet. Globally, on average, people seem to spend close to half their waking hours looking at screens, and among young people in the rich world the number is a good deal higher than that.

History teaches that new technologies always make possible new forms of exploitation, and this basic fact has been spectacularly exemplified by the rise of society-scale digital platforms. It has been driven by a remarkable new way of extracting money from human beings: call it “human fracking”. Just as petroleum frackers pump high-pressure, high-volume detergents into the ground to force a little monetisable black gold to the surface, human frackers pump high-pressure, high-volume detergent into our faces (in the form of endless streams of addictive slop and maximally disruptive user-generated content), to force a slurry of human attention to the surface, where they can collect it, and take it to market.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

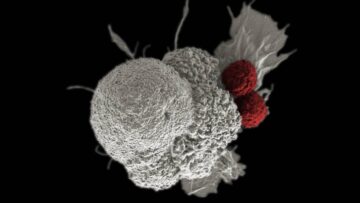

In First Human Trial, Zombie Cancer Cells Train the Body to Fight Tumors

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

Lights, vitamin, action. A combination of vitamin B2 and ultraviolet light hardly sounds like a next-generation cancer treatment. But a small new trial is testing the duo in people with recurrent ovarian cancer. Led by PhotonPharma, this first-in-humans study builds on decades of work investigating whether we can turn whole cancer cells into “vaccines.” Isolated from cancer patients, the cells are stripped of the ability to multiply but keep all other protein signals intact. Once reinfused, the cells can, in theory, alert the immune system that something is awry.

Lights, vitamin, action. A combination of vitamin B2 and ultraviolet light hardly sounds like a next-generation cancer treatment. But a small new trial is testing the duo in people with recurrent ovarian cancer. Led by PhotonPharma, this first-in-humans study builds on decades of work investigating whether we can turn whole cancer cells into “vaccines.” Isolated from cancer patients, the cells are stripped of the ability to multiply but keep all other protein signals intact. Once reinfused, the cells can, in theory, alert the immune system that something is awry.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Joel Primack (1945 – 2025) Physicist

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sunday Poem

Autumn in Portage

You told me autumn in Michigan is revealing

hidden behind yards of transgeographic distance

watching out leaves muddled on pavements like

last season’s motifs jotted in a diary kept away from

others, you must have touched your hair lingering

around lobes, those cracked lips wanting more than

this feast of yellow and russet, the Red oak spilling

wine and the Aspen grieving over getting yellowed

birches standing like seasoned saints absorbing frosting

egos, this witchcraft of visuals, out of the car’s window

made the most of the sight, clicking images for a foreign

hand to touch your autumn, not you wrapped in warmers.

by Rizwan Akhtar

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday, January 16, 2026

The Case for Financial Crime Bounty Hunters

Miles Kellerman at False Positive:

It was just the type of document I was hoping to find.

It was just the type of document I was hoping to find.

Buried beneath endless layers of digital files, each poorly labelled and filled with unsearchable PDFs, was an organizational structure chart. The presence of this chart was not, in itself, surprising. It is one of the many documents financial institutions are required to collect when performing due diligence on new customers. What made this chart notable was who it named as the company’s owner. Namely: an individual with alleged ties to a ruthless terrorist group.1

I was not reviewing these files as a regulator. Nor was I a journalist chasing down some lead. Rather, I was supporting a corporate monitorship, an obscure but highly consequential tool of criminal enforcement. Monitorships arise when prosecutors determine that a company has broken the law at scale. Perhaps a bank has been failing to perform due diligence for years, allowing North Korean agents to launder stolen funds through riverboat casinos. Or maybe it’s a mining conglomerate bribing officials across central Africa. You know, that kind of thing.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Discarding the Shaft-and-Belt Model of Software Development

Steve Newman at Second Thoughts:

It’s often been observed that taking full advantage of AI will require changing work practices, just as taking full advantage of electric motors in manufacturing required changing the way factories were laid out. But what will those changes look like? Early answers are starting to emerge, coming (unsurprisingly) from the field of software development. Interestingly, the biggest impacts may not be cost savings!

It’s often been observed that taking full advantage of AI will require changing work practices, just as taking full advantage of electric motors in manufacturing required changing the way factories were laid out. But what will those changes look like? Early answers are starting to emerge, coming (unsurprisingly) from the field of software development. Interestingly, the biggest impacts may not be cost savings!

My timeline is suddenly awash in engineers (including me!) reporting that Claude Code is revolutionizing their work. I can see the outlines of a new approach to software development, suited for the AI age. The implications may apply to other fields as well. The key ideas…

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Visualizing Richard Feynman’s lecture on the refractive index

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.