Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Category: Recommended Reading

Demis Hassabis, Dario Amodei Debate the World After AGI

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Stuff, Quality, Structure: The Whole Go

David Builes at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

As the reader might have guessed, the views that Strawson defends in the book are far apart from mainstream views in contemporary analytic metaphysics. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that the style of the book is also distinctive. For one, the focus of the book is on developing a unified “big picture” view of fundamental matters in metaphysics, so one might find less detailed argument and critical engagement with alternative views in this book than in other contemporary books in metaphysics, e.g., one could easily write an entire book on categorical monism, or on the powerful qualities view, or on thing-monism, or on kind-monism). The book also seamlessly incorporates references to the history of philosophy throughout. Although Strawson knows full well that his views are not very popular in contemporary metaphysics, he argues that many of his views have been endorsed by some of the most prominent philosophers throughout history (including Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Kant, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Whitehead, Russell, and others).

As the reader might have guessed, the views that Strawson defends in the book are far apart from mainstream views in contemporary analytic metaphysics. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that the style of the book is also distinctive. For one, the focus of the book is on developing a unified “big picture” view of fundamental matters in metaphysics, so one might find less detailed argument and critical engagement with alternative views in this book than in other contemporary books in metaphysics, e.g., one could easily write an entire book on categorical monism, or on the powerful qualities view, or on thing-monism, or on kind-monism). The book also seamlessly incorporates references to the history of philosophy throughout. Although Strawson knows full well that his views are not very popular in contemporary metaphysics, he argues that many of his views have been endorsed by some of the most prominent philosophers throughout history (including Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Kant, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Whitehead, Russell, and others).

In my view, Strawson does an excellent job of bringing out the intuitive motivations for the views that he discusses in an accessible manner, and I strongly recommend the book to anyone who is interested in fundamental metaphysics. In what follows, I will focus on two of Strawson’s main claims: categorical monism and the powerful qualities view.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

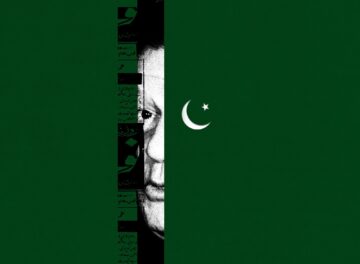

The Hidden Imran: Pakistan’s most famous man

Osman Samiuddin at Equator:

Just so we’re clear, the following is a fact. Not opinion, not a point of view, not a hot take. Fact. There is no Pakistani – male, female, dead, alive, real, imagined – as famous as Imran Khan. Every turn in a multifarious public life has abounded in fame, first as a cricket legend, then as a beloved philanthropist who built a cancer hospital for the poor, latterly as a maverick politician who swept to power promising reform, and now, as the sole occupant of a cell in Pakistan’s most notorious jail. So famous he’s been the subject of two death hoaxes – most recently in November, when he went unseen for so long that many concluded he had died.

Just so we’re clear, the following is a fact. Not opinion, not a point of view, not a hot take. Fact. There is no Pakistani – male, female, dead, alive, real, imagined – as famous as Imran Khan. Every turn in a multifarious public life has abounded in fame, first as a cricket legend, then as a beloved philanthropist who built a cancer hospital for the poor, latterly as a maverick politician who swept to power promising reform, and now, as the sole occupant of a cell in Pakistan’s most notorious jail. So famous he’s been the subject of two death hoaxes – most recently in November, when he went unseen for so long that many concluded he had died.

There have been others with greater accomplishments. There may come others in the future. But in 78 years of Pakistan, in the pure currency of fame, of being known and recognised, of being talked about, of being the one Pakistani everyone can name, there is nobody beyond Imran. It holds even now, two years into the state’s attempts to erase him from public life.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Cheating with John Cheever

Jessica Laser at The Paris Review:

When I read the story, I was convalescing from an affair with a married person. I did love him back, and he didn’t change his life for me, and since you can’t heal at home from a heartbreak nobody knows about, I had gone abroad. Nothing in my life seemed to be working, and I must have searched up Cheever as part of my attempt to try the opposite of everything I had been doing. I had to admit that in the mirror “The Country Husband” held up to me, I appeared a little less broken than I felt. Writing from Francis Weed’s point of view, Cheever had, at a time when I really needed it, validated my experience of how powerful and real and obliterating extramarital love can be—even and especially for the married party. This, by the way, was years before the ubiquity of open marriages made moot the need for affairs, the way de Tocqueville has described the democratic election’s quelling the need for violent revolution. But the impulse to escape, resist, defy; the flirting with destruction, complete overhaul, change—this doesn’t go away just because one container for it has gone licit.

When I read the story, I was convalescing from an affair with a married person. I did love him back, and he didn’t change his life for me, and since you can’t heal at home from a heartbreak nobody knows about, I had gone abroad. Nothing in my life seemed to be working, and I must have searched up Cheever as part of my attempt to try the opposite of everything I had been doing. I had to admit that in the mirror “The Country Husband” held up to me, I appeared a little less broken than I felt. Writing from Francis Weed’s point of view, Cheever had, at a time when I really needed it, validated my experience of how powerful and real and obliterating extramarital love can be—even and especially for the married party. This, by the way, was years before the ubiquity of open marriages made moot the need for affairs, the way de Tocqueville has described the democratic election’s quelling the need for violent revolution. But the impulse to escape, resist, defy; the flirting with destruction, complete overhaul, change—this doesn’t go away just because one container for it has gone licit.

Cheever lived with his wife and children in the real Westchester, during a time when, as Susan Cheever’s new memoir reminds us, you could pay for your daughter’s braces by publishing a short story.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Chuck Mangione Land of Make Believe

(Note: For Ga and Jim who introduced me to CM in 1974.)

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

It Makes Sense That People See A.I. as God

Joseph Bernstein in The New York Times:

Hark! A sign of the End Times. No, not the Four Horsemen, nor a black sun, nor the resurrection of the dead. The omen that the rapture is upon us is none other than artificial intelligence.

Hark! A sign of the End Times. No, not the Four Horsemen, nor a black sun, nor the resurrection of the dead. The omen that the rapture is upon us is none other than artificial intelligence.

At least, such is the prophecy that has issued forth from the great syncretic dorm room of American culture: Joe Rogan’s mind. In November, the most popular podcaster in the country suggested that the next holy manger might be located not in the Middle East, but inside a mainframe instead. “Jesus was born out of a virgin mother; what’s more virgin than a computer?” he mused on the “American Alchemy” podcast. He added: “If Jesus does return — even if Jesus was a physical person in the past — you don’t think that he could return as artificial intelligence?”

After all, he noted: “It reads your mind, and it loves you.”

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Friday Poem

the Falls of the Ohio on October 26, 1803.

God’s House

.

By Frank X Walker

From: Buffalo Dance: The Journey of York

Accents Publishing, 2022

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday, January 22, 2026

The Philosophy of Owen Barfield

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

On Writers and Their Day Jobs

Ed Simon at Literary Hub:

For nineteen years, until his retirement in 1885, Herman Melville would awake, slick back his dark hair and unsnarl the snags from his beard, don a uniform of dark navy pilot cloth and affix to his chest the brass badge of a U.S. Customs Inspector. Operating at the Lower Manhattan docks, Melville’s task was to examine ship manifests against unloaded cargo. “I am tormented with an everlasting itch for things remote,” said Ishmael in Moby-Dick. “I love to sail forbidden seas, and land on barbarous coasts.”

For nineteen years, until his retirement in 1885, Herman Melville would awake, slick back his dark hair and unsnarl the snags from his beard, don a uniform of dark navy pilot cloth and affix to his chest the brass badge of a U.S. Customs Inspector. Operating at the Lower Manhattan docks, Melville’s task was to examine ship manifests against unloaded cargo. “I am tormented with an everlasting itch for things remote,” said Ishmael in Moby-Dick. “I love to sail forbidden seas, and land on barbarous coasts.”

Before penning those watery books Typee, Benito Cereno, The Confidence Man, and Billy Budd (and of course the one about the whale), Melville had been a sailor on the St. Lawrence in 1839, a harpooner aboard the Acushnet in 1841, even a mutineer briefly on the Lucy Ann a year later. In middle age, though, the only seaway Melville encountered was the brackish Hudson and his journeys consisted of tabulating the wool unloaded from Manchester, rum from Havana, and tea from Calcutta.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Somebody Is Walking on Your Grave

Mariana Enriquez at Bomb Magazine:

New Orleans has around 350 thousand inhabitants—over a million if you include its metropolitan area—and forty-two cemeteries. That’s a lot. Graves here are aboveground; there are almost no burials. The city is in a swamp, so close to the water table that it’s as if it were floating. To attempt an underground grave means condemning the coffin to float out someday, when the water rises. That’s why there are only niches, vaults, mausoleums.

New Orleans has around 350 thousand inhabitants—over a million if you include its metropolitan area—and forty-two cemeteries. That’s a lot. Graves here are aboveground; there are almost no burials. The city is in a swamp, so close to the water table that it’s as if it were floating. To attempt an underground grave means condemning the coffin to float out someday, when the water rises. That’s why there are only niches, vaults, mausoleums.

St. Louis No. 1 is the city’s oldest cemetery. It’s not far from Congo Square, the plaza where, two hundred years ago, enslaved people could congregate, dance, sing, and were even allowed to drum. That’s where jazz was born. For many years, the graves of St. Louis No. 1 were crumbling and collapsing, and bones were scattered. The city’s cemeteries were badly neglected. However, for some time now, NGOs have been working to protect and restore them—in particular, Save Our Cemeteries, which takes care of all New Orleans graveyards. No other city in the world has so many: New Orleans has forty-two cities of the dead.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Filoplumes: Nature’s Super Feathers

Jim Robbins in the New York Times:

Vanya Gregor Rohwer slid open a drawer to display the rich pink spread wing of a roseate spoonbill, one of thousands of mounted wings at the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates.

Vanya Gregor Rohwer slid open a drawer to display the rich pink spread wing of a roseate spoonbill, one of thousands of mounted wings at the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates.

He pulled up a long flight feather to expose, at its base, a palm-tree shaped feather so minuscule it could easily be missed. For a long time, this tiny feature called a filoplume was indeed obscure.

“The history of research on filoplumes is not super robust. They are kind of an overlooked feather,” said Dr. Rohwer, a curator of birds and mammals at the museum. “They were considered a degenerate feather or a useless feather, a relic.”

No longer.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The Life of Indian Physicist Satyendra Nath Bose

Somaditya (Soma) Banerjee at Aeon Magazine:

On a summer day in 1924, a young Indian physicist named Satyendra Nath Bose sent a paper and a letter to Albert Einstein. It would shape the nascent field of quantum mechanics and secure Bose a place in the annals of scientific history.

On a summer day in 1924, a young Indian physicist named Satyendra Nath Bose sent a paper and a letter to Albert Einstein. It would shape the nascent field of quantum mechanics and secure Bose a place in the annals of scientific history.

At the time, Bose was teaching in colonial India, thousands of miles from the centres of European science. In his letter, the 30-year-old Bose explained that he had found a more elegant way to derive one of the pivotal laws of physics (Planck’s law of radiation) and asked for Einstein’s help in publishing it. To Bose’s astonishment, Einstein replied enthusiastically. He translated Bose’s manuscript into German and arranged for it to be published in Zeitschrift für Physik, a leading physics journal of the time. Thus was born Bose-Einstein statistics, a cornerstone of quantum physics.

What made it so significant? In plain terms, Bose devised a new way to count and describe the behaviour of identical quantum particles, most famously, particles of light called photons.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sean Carroll: The problem with pretending quantum mechanics makes sense

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

How The ‘AI Job Shock’ Will Differ From The ‘China Trade Shock’

Nathan Gardels at Noema:

Among the job doomsayers of the AI revolution, David Autor is a bit of an outlier. As the MIT economist has written in Noema, the capacity of mid-level professions such as nursing, design or production management to access greater expertise and knowledge once available only to doctors or specialists will boost the “applicable” value of their labor, and thus the wages and salaries that can sustain a middle class.

Among the job doomsayers of the AI revolution, David Autor is a bit of an outlier. As the MIT economist has written in Noema, the capacity of mid-level professions such as nursing, design or production management to access greater expertise and knowledge once available only to doctors or specialists will boost the “applicable” value of their labor, and thus the wages and salaries that can sustain a middle class.

Unlike rote, low-level clerical work, cognitive labor of this sort is more likely to be augmented by decision-support information afforded by AI than displaced by intelligent machines.

By contrast, “inexpert” tasks, such as those performed by retirement home orderlies, child-care providers, security guards, janitors or food service workers, will be poorly remunerated even as they remain socially valuable. Since these jobs cannot be automated or enhanced by further knowledge, those who labor in them are a “bottleneck” to improved productivity that would lead to higher wages. Since there will be a vast pool of people without skills who can take those jobs, the value of their labor will be driven down even further.

This is problematic from the perspective of economic disparity because four out of every five jobs created in the U.S. are in this service sector.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

What Goes Wrong in Cancer?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The real da Vinci code

From Science:

In April 2024, microbial geneticist Norberto Gonzalez-Juarbe stood over an enigmatic drawing in a private New York City collection. Gently, he rubbed its centuries-old surface, front and back, with a swab like those used in COVID-19 testing. “It’s not every day,” Gonzalez-Juarbe recalls with a laugh, “that one gets to touch a Leonardo.” Rendered in red chalk on paper, Holy Child shows a young boy’s head inclined slightly to the side, his features sketched with feathery strokes. Light pools softly around his cheeks and brow, dissolving the edges of his pensive face in a haze of sfumato. The late art dealer Fred Kline, who acquired the drawing in the early 2000s, had claimed stylistic features such as left-handed hatching, a trademark of Leonardo da Vinci’s, link Holy Child to the Renaissance master. But its authorship remains in dispute; experts say one of his students could have produced it.

In April 2024, microbial geneticist Norberto Gonzalez-Juarbe stood over an enigmatic drawing in a private New York City collection. Gently, he rubbed its centuries-old surface, front and back, with a swab like those used in COVID-19 testing. “It’s not every day,” Gonzalez-Juarbe recalls with a laugh, “that one gets to touch a Leonardo.” Rendered in red chalk on paper, Holy Child shows a young boy’s head inclined slightly to the side, his features sketched with feathery strokes. Light pools softly around his cheeks and brow, dissolving the edges of his pensive face in a haze of sfumato. The late art dealer Fred Kline, who acquired the drawing in the early 2000s, had claimed stylistic features such as left-handed hatching, a trademark of Leonardo da Vinci’s, link Holy Child to the Renaissance master. But its authorship remains in dispute; experts say one of his students could have produced it.

Gonzalez-Juarbe’s swabs may have captured a biological clue. In a remarkable milestone in a decadelong odyssey, he and other members of the Leonardo da Vinci DNA Project (LDVP), a global scientific collective, report in a paper posted today on bioRxiv that they have recovered DNA from Holy Child and other objects—and some may be from Leonardo himself.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Thursday Poem

How to Teach a Child to Pray

Humiliate her at every checkpoint. Replace

the Second Surah with air raids and shelling.

—

Reduce everything she knows to rubble.

Bury her younger brother under his school.

—

Laugh when she raises her hands in front of her face

and asks your God for peace.

—

Surveil her dreams of clean water and fresh bread.

Reduce everything she knows to rubble, again.

—

Direct her to ignore the smell of decaying bodies

when bowing down to perform Ruku.

—

Strip search her grandparents in the street

let her hold their shame.

—

Expect her gratitude for being able to count

on one hand cousins who have one hand.

—

Teach her to dread shelters and refugee camps

instead of periods.

—

Assume her capacity to forgive will be longer

than her memory.

—

Dare her to stand up and repeat

“God is Good!.”

—

by Frank X Walker

from Kinfolk.

Poetry Magazine January/February 2026 issue of Poetry.

—

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Wednesday, January 21, 2026

Could This Portrait of an Elderly Man With a Young Woman’s Face Hidden in His Beard Be a Long-Lost Study by Peter Paul Rubens?

Sonja Anderson at Smithsonian Magazine:

Three years ago, Belgian art dealer Klaas Muller paid about $115,000 for an undated, unsigned painting of an elderly man. Offered online by a “lesser-known auction house in northern Europe,” the piece was billed as a study by an unknown master of the “Flemish school,” Muller tells the Guardian’s Philip Oltermann.

Three years ago, Belgian art dealer Klaas Muller paid about $115,000 for an undated, unsigned painting of an elderly man. Offered online by a “lesser-known auction house in northern Europe,” the piece was billed as a study by an unknown master of the “Flemish school,” Muller tells the Guardian’s Philip Oltermann.

However, the oil-on-paper piece may be the work of Peter Paul Rubens, the renowned Flemish painter of the 17th century. When Muller first glimpsed the warm-toned painting—depicting a man gazing downward past his long, wavy beard—he recognized something in it.

“I wasn’t sure it was a Rubens. I just knew it was very Rubens-esque, so it was still a gamble,” Muller tells the Guardian. “I have a library of books about [Rubens] at home and look at them most evenings. … It’s a bit of an addiction.”

Muller also thought the man in the painting looked familiar. He guessed it was St. Peter the Apostle or the Roman god Neptune, he tells the Belgian newspaper De Standaard’s Geert Sels. Muller began combing his reference books.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Does OnlyFans Empower Or Exploit Women?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.