Category: Recommended Reading

The Voice-O-Graph

Laura Preston at The Believer:

From our contemporary vantage point, voice mail may seem like a quaint artifact of the ’80s and ’90s. But the answering machine was in fact preceded by a lesser-known era of voice messaging, one which began in the early 1900s and grew out of the phonograph. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, and before he unveiled the device to the public, he spent some time colliding morphemes in a notebook. He thought he might call his invention the “antiphone” (back-talker) or the “liguphone” (clear speaker), or perhaps the “bittakophone” (parrot speaker), “hemerologophone” (speaking almanac), or “trematophone” (sound borer). In the end, Edison settled on the straightforward “phonograph,” meaning “sound writer”—an efficient summary of its mechanism. The phonograph received vibrations from the air and transcribed them as calligraphy. Sound waves would cause a needle to quiver, and the needle would etch a continuous line on a turning cylinder. If you reversed the process, the needle would travel along the groove, mining sound from the uneven topography and playing it back through a horn.

From our contemporary vantage point, voice mail may seem like a quaint artifact of the ’80s and ’90s. But the answering machine was in fact preceded by a lesser-known era of voice messaging, one which began in the early 1900s and grew out of the phonograph. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, and before he unveiled the device to the public, he spent some time colliding morphemes in a notebook. He thought he might call his invention the “antiphone” (back-talker) or the “liguphone” (clear speaker), or perhaps the “bittakophone” (parrot speaker), “hemerologophone” (speaking almanac), or “trematophone” (sound borer). In the end, Edison settled on the straightforward “phonograph,” meaning “sound writer”—an efficient summary of its mechanism. The phonograph received vibrations from the air and transcribed them as calligraphy. Sound waves would cause a needle to quiver, and the needle would etch a continuous line on a turning cylinder. If you reversed the process, the needle would travel along the groove, mining sound from the uneven topography and playing it back through a horn.

more here.

Hegel’s Aesthetics

William Desmond at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

One might amplify the point: it is surprising that Hegel’s aesthetic has suffered neglect in our own postmodern age, so-called, when the preeminence of the aesthetic is so marked, to the diminution of the religious, and the sterilization of the philosophical in its high idealistic ambitions. In the quarrel between the poets and the philosophers, the post-Nietzscheans have decided in favor of the poets, and one might expect the richness of Hegel’s aesthetics to be accorded some honorable place in that context. Perhaps the neglect reflects the fact that in the end Hegel places philosophy in an ultimate position in absolute spirit, and indeed seems to place the absolute spiritual significance of the aesthetic behind us. There is an element of discordance with Hegel’s proclamation of the end of art in a time when art seems to have displaced the religious in the lists of spiritual ultimacy, and philosophy itself has contented itself with being more or less an academic specialty, whether of an analytical or hermeneutical sort. Hegel is discordant in that post-Hegelian culture has tended to place in art high hopes for a suitable replacement of lost religious transcendence. It is notable even among philosophers at least in the continental tradition, that art has assumed unprecedented (sometimes metaphysical) significance: Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Adorno, Merleau-Ponty, Badiou, to name some.

One might amplify the point: it is surprising that Hegel’s aesthetic has suffered neglect in our own postmodern age, so-called, when the preeminence of the aesthetic is so marked, to the diminution of the religious, and the sterilization of the philosophical in its high idealistic ambitions. In the quarrel between the poets and the philosophers, the post-Nietzscheans have decided in favor of the poets, and one might expect the richness of Hegel’s aesthetics to be accorded some honorable place in that context. Perhaps the neglect reflects the fact that in the end Hegel places philosophy in an ultimate position in absolute spirit, and indeed seems to place the absolute spiritual significance of the aesthetic behind us. There is an element of discordance with Hegel’s proclamation of the end of art in a time when art seems to have displaced the religious in the lists of spiritual ultimacy, and philosophy itself has contented itself with being more or less an academic specialty, whether of an analytical or hermeneutical sort. Hegel is discordant in that post-Hegelian culture has tended to place in art high hopes for a suitable replacement of lost religious transcendence. It is notable even among philosophers at least in the continental tradition, that art has assumed unprecedented (sometimes metaphysical) significance: Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Adorno, Merleau-Ponty, Badiou, to name some.

more here.

Animals, Sex and Guns? Eric Goode Knew ‘Tiger King’ Had Potential

Dave Itzkoff in The New York Times:

When he set out to investigate the inner world of exotic animal breeders, Eric Goode had no idea he would end up making the hit Netflix series “Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness.”

When he set out to investigate the inner world of exotic animal breeders, Eric Goode had no idea he would end up making the hit Netflix series “Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness.”

Released less than two weeks ago, the series is already a sensation, immersing viewers in the lives and rivalries of vivid subjects like Bhagavan Antle, known as Doc, the bombastic proprietor of an animal preserve and safari tour in Myrtle Beach, S.C., and Carole Baskin, an animal activist and sanctuary owner in Tampa, Fla., whose former husband disappeared in 1997. And then, of course, there’s the Tiger King himself, Joseph Maldonado-Passage, better known as Joe Exotic, a flamboyant Oklahoma zookeeper, political candidate and aspiring celebrity who was sentenced in January to 22 years in prison for his involvement in a failed plot to kill Baskin and for killing five tiger cubs. Goode, who directed “Tiger King” with Rebecca Chaiklin, said that he had been reasonably confident the series would be successful. “How can you not be fascinated with polygamy, drugs, cults, tigers, potential murder?” Goode said in an interview on Tuesday. “It had all the ingredients that one finds salacious. So we knew that there would be an appetite for it.”

But he could hardly have suspected that “Tiger King” would arrive during the coronavirus pandemic, during which audiences have had ample time to pore over its jaw-dropping plot twists while they shelter in their homes. For some viewers, “Tiger King” has also been an introduction to Goode, 62, a founder of the fabled 1980s-era New York nightspot Area who is now an owner of downtown Manhattan establishments like the Bowery Hotel and the Waverly Inn. In an interview, Chaiklin said she first worked for Goode in the mid 1990s as a door girl and manager at the Bowery Bar and Grill. More recently, over a “crazy posh dinner,” Goode first told her about the wild kingdoms they would end up traveling together.

More here.

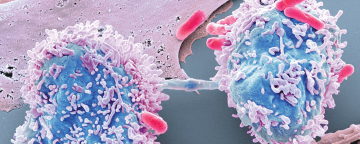

Bacteria as Living Microrobots to Fight Cancer

Simone Schuerle, and Tal Danino in The Scientist:

In the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, a team of scientists is shrunk to fit into a tiny submarine so that they can navigate their colleague’s vasculature and rid him of a deadly blood clot in his brain. This classic film is one of many such imaginative biological journeys that have made it to the big screen over the past several decades. At the same time, scientists have been working to make a similar vision a reality: tiny robots roaming the human body to detect and treat disease.

In the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, a team of scientists is shrunk to fit into a tiny submarine so that they can navigate their colleague’s vasculature and rid him of a deadly blood clot in his brain. This classic film is one of many such imaginative biological journeys that have made it to the big screen over the past several decades. At the same time, scientists have been working to make a similar vision a reality: tiny robots roaming the human body to detect and treat disease.

Although systems with nanomotors and onboard computation for autonomous navigation remain fodder for fiction, researchers have designed and built a multitude of micro- and nanoscale systems for diagnostic and therapeutic applications, especially in the context of cancer, that could be considered early prototypes of nanorobots. Since 1995, more than 50 nanopharmaceuticals, basically some sort of nanoscale device incorporating a drug, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. If a drug of this class possesses one or more robotic characteristics, such as sensing, onboard computation, navigation, or a way to power itself, scientists may call it a nanorobot. It could be a nanovehicle that carries a drug, navigates to or preferentially aggregates at a tumor site, and opens up to release a drug only upon a certain trigger. The first approved nanopharmaceutical was DOXIL, a liposomal nanoshell carrying the chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin, which nonselectively kills cells and is commonly used to treat a range of cancers. The intravenously administered nanoshells preferentially accumulate in tumors, thanks to a leaky vasculature and inadequate drainage by the lymphatic system. There, the nanoparticles slowly release the drug over time. In that sense, basic forms of nanorobots are already in clinical use.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Small Comfort

Coffee and cigarettes in a clean cafe,

forsythia lit like a damp match against

a thundery sky drunk on its own ozone,

the laundry cool and crisp and folded away

again in the lavender closet —too late to find

comfort enough in such small daily moments

of beauty, renewal, calm, too late to imagine

people would rather be happy than suffering

and inflicting suffering. We’re near the end,

but O before the end, as the sparrows wing

each night to their secret nests in the elm’s green dome

O let the last bus bring

love to lover, let the starveling

dog turn the corner and lope suddenly

miraculously, down its own street, home.

by Katha Pollitt

from Poetry 180

Random House, 2003

Wednesday, April 1, 2020

Ken Roth: How Authoritarians Are Exploiting the Covid-19 Crisis to Grab Power

Ken Roth in the New York Review of Books:

For authoritarian-minded leaders, the coronavirus crisis is offering a convenient pretext to silence critics and consolidate power. Censorship in China and elsewhere has fed the pandemic, helping to turn a potentially containable threat into a global calamity. The health crisis will inevitably subside, but autocratic governments’ dangerous expansion of power may be one of the pandemic’s most enduring legacies.

For authoritarian-minded leaders, the coronavirus crisis is offering a convenient pretext to silence critics and consolidate power. Censorship in China and elsewhere has fed the pandemic, helping to turn a potentially containable threat into a global calamity. The health crisis will inevitably subside, but autocratic governments’ dangerous expansion of power may be one of the pandemic’s most enduring legacies.

In times of crisis, people’s health depends at minimum on free access to timely, accurate information. The Chinese government illustrated the disastrous consequence of ignoring that reality. When doctors in Wuhan tried to sound the alarm in December about the new coronavirus, authorities silenced and reprimanded them. The failure to heed their warnings gave Covid-19 a devastating three-week head start. As millions of travelers left or passed through Wuhan, the virus spread across China and around the world.

Even now, the Chinese government is placing its political goals above public health. It claims that the coronavirus has been tamed but won’t allow independent verification. It is expelling journalists from several leading US publications, including those that have produced incisive reporting, and has detained independent Chinese reporters who venture to Wuhan. Meanwhile, Beijing is pushing wild conspiracy theories about the origin of the virus, hoping to deflect attention from the tragic results of its early cover-up.

Others are following China’s example.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: David Kaiser on Science, Money, and Power

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Science costs money. And for a brief, glorious period between the start of the Manhattan Project in 1939 and the cancellation of the Superconducting Super Collider in 1993, physics was awash in it, largely sustained by the Cold War. Things are now different, as physics — and science more broadly — has entered a funding crunch. David Kaiser, who is both a working physicist and an historian of science, talks with me about the fraught relationship between scientists and their funding sources throughout history, from Galileo and his patrons to the current rise of private foundations. It’s an interesting listen for anyone who wonders about the messy reality of how science gets done.

Science costs money. And for a brief, glorious period between the start of the Manhattan Project in 1939 and the cancellation of the Superconducting Super Collider in 1993, physics was awash in it, largely sustained by the Cold War. Things are now different, as physics — and science more broadly — has entered a funding crunch. David Kaiser, who is both a working physicist and an historian of science, talks with me about the fraught relationship between scientists and their funding sources throughout history, from Galileo and his patrons to the current rise of private foundations. It’s an interesting listen for anyone who wonders about the messy reality of how science gets done.

More here.

Corona Affairs, Iranian Style

Mohammad Memarian in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

On Friday, March 20, I called my father to congratulate him on the Persian New Year. It felt gloomy, to put it mildly. We used to do it in person, shaking hands, hugging, and the three traditional kisses on the cheeks. As we are in self-quarantine, 300 miles away from each other, he acquired his very first smartphone just a week ago, rapidly catching up with technology to keep in touch with me. I watched him as he tried to turn on the selfie camera. He kept the phone so close that I could only see him with difficulty. But I could observe parts of him that usually go unnoticed: details of the wrinkles on his face, the tears he was struggling to hold back, a bruise on his left cheek, speckles I hadn’t seen before. We talked for a while, five minutes maybe, the longest routine call we had in years, and then we retreated into solitude, each into his own. The whole episode reminded me of stories of families torn apart by immigration. We are now torn apart by another, equally invisible force.

On Friday, March 20, I called my father to congratulate him on the Persian New Year. It felt gloomy, to put it mildly. We used to do it in person, shaking hands, hugging, and the three traditional kisses on the cheeks. As we are in self-quarantine, 300 miles away from each other, he acquired his very first smartphone just a week ago, rapidly catching up with technology to keep in touch with me. I watched him as he tried to turn on the selfie camera. He kept the phone so close that I could only see him with difficulty. But I could observe parts of him that usually go unnoticed: details of the wrinkles on his face, the tears he was struggling to hold back, a bruise on his left cheek, speckles I hadn’t seen before. We talked for a while, five minutes maybe, the longest routine call we had in years, and then we retreated into solitude, each into his own. The whole episode reminded me of stories of families torn apart by immigration. We are now torn apart by another, equally invisible force.

This invisible force, otherwise known as COVID-19, intruded into our lives in pretty much the same way it did into the lives of countless other people elsewhere. Except, perhaps, the context. For us Iranians, the disease came as the culmination of a long streak of unfortunate events, which inflicted upon many here a deep sense of helplessness.

More here.

Simulating an epidemic

The Munich Necromancer’s Manual

Dorothea Lange’s Angel of History

Rebecca Solnit at The Paris Review:

This woman seems to have been standing in the meadow forever, with it and of it, welcoming us all, an earthbound archangel of the topsoil. You could imagine that below her housedress her feet have taken root or her torso has become a tree trunk, and the way she smiles and reaches out that right hand seems like the most generous way to say that this place is hers.

Everything in the picture affirms a sense of stability. The square photograph is bisected horizontally by the straight line where the flowering meadow joins the bare hill on the right and the tree-covered hill on the left that rise up from either side of her like wings. That line is even with her bosom, and her outstretched hand seems almost to rest on it.

more here.

Lives of Houses

Kevin Jackson at Literary Review:

My favourite essay, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst’s ‘At Home with Tennyson’, is both a bravura work of close reading and a highly sensitive study of the poet’s loyalties, yearnings and fears about homes and homelessness. Tennyson, he demonstrates, was profoundly touched by the idea of home and ‘was equally good at evoking home when it existed only as an idea, as in “The Lotos-Eaters”, where so much of what the speaker broods over – “roam”, “foam”, “honeycomb” – has the word “home” flickering through it like a nagging but elusive memory’. Douglas-Fairhurst is yet another of the essayists here to be attracted by the word ‘nest’: Tennyson produces a ‘voice that is keen to create a nest of words for itself but also appears to be nervously eyeing up the lines of each stanza like a little set of prison bars’. This is criticism that draws quite close to the status of poetry.

My favourite essay, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst’s ‘At Home with Tennyson’, is both a bravura work of close reading and a highly sensitive study of the poet’s loyalties, yearnings and fears about homes and homelessness. Tennyson, he demonstrates, was profoundly touched by the idea of home and ‘was equally good at evoking home when it existed only as an idea, as in “The Lotos-Eaters”, where so much of what the speaker broods over – “roam”, “foam”, “honeycomb” – has the word “home” flickering through it like a nagging but elusive memory’. Douglas-Fairhurst is yet another of the essayists here to be attracted by the word ‘nest’: Tennyson produces a ‘voice that is keen to create a nest of words for itself but also appears to be nervously eyeing up the lines of each stanza like a little set of prison bars’. This is criticism that draws quite close to the status of poetry.

more here.

Ending Covid: It will take some time, but rest assured: a coronavirus vaccine is coming, and it will work

Peter Kolchinsky in City Journal:

The biopharmaceutical industry will be able to make a Covid-19 vaccine— probably a few of them—using various existing vaccine technologies. But many people worry that Covid-19 will mutate and evade our vaccines, as the flu virus does each season. Covid-19 is fundamentally different from flu viruses, though, in ways that will allow our first-generation vaccines to hold up well. To the extent that Covid does mutate, it’s likely to do so much more slowly than the flu virus does, buying us time to create new and improved vaccines. Every virus has a genome composed of genetic material (either RNA or DNA) that encodes instructions for replicating the virus. When a virus infects a cell, it accesses machinery for making copies of its genomic instructions and follows those instructions to make viral proteins that assemble, with copies of the instructions, to form more viruses (which then pop out of the cell to infect new cells, either in the same host or in someone new). There is a critical difference between coronaviruses and flu. The novel coronavirus genome is made of one long strand of genetic code. This makes it an “unsegmented” virus—like a set of instructions that fit on a single page. The flu virus has eight genomic segments, so its code fits on eight “pages.” That’s not common for viruses, and it gives the flu a special ability. Because the major parts of the flu virus are described on separate pages (segments) of its genome, when two different flu viruses infect the same cell, they can swap pages.

The biopharmaceutical industry will be able to make a Covid-19 vaccine— probably a few of them—using various existing vaccine technologies. But many people worry that Covid-19 will mutate and evade our vaccines, as the flu virus does each season. Covid-19 is fundamentally different from flu viruses, though, in ways that will allow our first-generation vaccines to hold up well. To the extent that Covid does mutate, it’s likely to do so much more slowly than the flu virus does, buying us time to create new and improved vaccines. Every virus has a genome composed of genetic material (either RNA or DNA) that encodes instructions for replicating the virus. When a virus infects a cell, it accesses machinery for making copies of its genomic instructions and follows those instructions to make viral proteins that assemble, with copies of the instructions, to form more viruses (which then pop out of the cell to infect new cells, either in the same host or in someone new). There is a critical difference between coronaviruses and flu. The novel coronavirus genome is made of one long strand of genetic code. This makes it an “unsegmented” virus—like a set of instructions that fit on a single page. The flu virus has eight genomic segments, so its code fits on eight “pages.” That’s not common for viruses, and it gives the flu a special ability. Because the major parts of the flu virus are described on separate pages (segments) of its genome, when two different flu viruses infect the same cell, they can swap pages.

Imagine two people with eight-page reports fighting over a copy machine. In the tussle, some copies might turn out to have a mix of pages from two different reports. This page-swapping process, where viruses exchange parts of their genome, is called reassortment. The flu can change rapidly when multiple strains pass through the same host. But coronavirus, as a one-page report, tends to stay together, and while coronaviruses can swap sections—in a process known as recombination—it is difficult to achieve and thus rare. (Imagine two pages ripping in the same way and swapping pieces that get glued together again.)

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Take This Poem and Copy it

Take this poem and copy it in your handwriting on a piece of paper and insert words from your soul between the words your hands copied. And notice the additions made by the words from your hands and the subtractions made by punctuation, the spaces and the lines which are broken within your life. Take this poem and copy it a thousand times and distribute it to people on the city’s main street. And say to them I wrote this poem this is a poem I wrote this is a poem I wrote this I wrote this poem I wrote this I wrote this I wrote. Take this poem and put it in an envelope and send it to the one your heart desires and include a short letter with it. And before you send it change its title and at the end add rhymes of your own. Sweeten the bitter and enrich the spare and bridge the cracked and simplify the clumsy and enliven the dead and square the truth. A person could take many poems and make them his. Take this very poem and make only this one yours for even though it has nothing special which ignites your desire to make it yours it also has no possessiveness of the kind which says a man’s poems are his property and his only and you have no right to meddle or ask anything of them but this is a poem which asks you to meddle with it to erase and to add and it is given to you freely for free ready to be changed by your hands. Take this poem and make it yours and sign your name on it and erase the previous name but remember it and remember that every word is poetry is the offspring of poetry and poetry is the poetry of many not one. And someone after you will take your poem and make it his and command those after him the children of poets take this poem and copy it on a piece of paper and make it yours in your handwriting.

by Almog Behar

from Wells’ Thirst

publisher: Am Oved, Tel Aviv,2008

Translation: 2017, Alexandra Berger-Polsky

Coronavirus lockdowns have changed the way Earth moves

Elizabeth Gibney in Nature:

The coronavirus pandemic has brought chaos to lives and economies around the world. But efforts to curb the spread of the virus might mean that the planet itself is moving a little less. Researchers who study Earth’s movement are reporting a drop in seismic noise — the hum of vibrations in the planet’s crust — that could be the result of transport networks and other human activities being shut down. They say this could allow detectors to spot smaller earthquakes and boost efforts to monitor volcanic activity and other seismic events. A noise reduction of this magnitude is usually only experienced briefly around Christmas, says Thomas Lecocq, a seismologist the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Brussels, where the drop has been observed. Just as natural events such as earthquakes cause Earth’s crust to move, so do vibrations caused by moving vehicles and industrial machinery. And although the effects from individual sources might be small, together they produce background noise, which reduces seismologists’ ability to detect other signals occurring at the same frequency.

The coronavirus pandemic has brought chaos to lives and economies around the world. But efforts to curb the spread of the virus might mean that the planet itself is moving a little less. Researchers who study Earth’s movement are reporting a drop in seismic noise — the hum of vibrations in the planet’s crust — that could be the result of transport networks and other human activities being shut down. They say this could allow detectors to spot smaller earthquakes and boost efforts to monitor volcanic activity and other seismic events. A noise reduction of this magnitude is usually only experienced briefly around Christmas, says Thomas Lecocq, a seismologist the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Brussels, where the drop has been observed. Just as natural events such as earthquakes cause Earth’s crust to move, so do vibrations caused by moving vehicles and industrial machinery. And although the effects from individual sources might be small, together they produce background noise, which reduces seismologists’ ability to detect other signals occurring at the same frequency.

Data from a seismometer at the observatory show that measures to curb the spread of COVID-19 in Brussels caused human-induced seismic noise to fall by about one-third, says Lecocq. The measures included closing schools, restaurants and other public venues from 14 March, and banning all non-essential travel from 18 March (see ‘Seismic noise’). The current drop has boosted the sensitivity of the observatory’s equipment, improving its ability to detect waves in the same high frequency range as the noise. The facility’s surface seismometer is now almost as sensitive to small quakes and quarry blasts as a counterpart detector buried in a 100-metre borehole, he adds. “This is really getting quiet now in Belgium.”

More here.

Tuesday, March 31, 2020

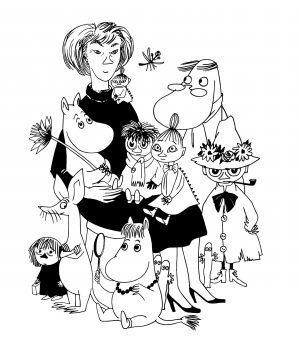

Inside Tove Jansson’s Private Universe

Sheila Heti at The New Yorker:

In the nineteen-fifties and sixties, one of the most famous cartoonists in the world was a lesbian artist who lived on a remote island off the coast of Finland. Tove Jansson had the status of a beloved cultural icon—adored by children, celebrated by adults. Before her death, in 2001, at the age of eighty-six, Jansson produced paintings, novels, children’s books, magazine covers, political cartoons, greeting cards, librettos, and much more. But most of Jansson’s fans arrived by way of the Moomins, a friendly species of her invention—rotund white creatures that look a little like upright hippos, and were the subject of nine best-selling books and a daily comic strip that ran for twenty years.

In the nineteen-fifties and sixties, one of the most famous cartoonists in the world was a lesbian artist who lived on a remote island off the coast of Finland. Tove Jansson had the status of a beloved cultural icon—adored by children, celebrated by adults. Before her death, in 2001, at the age of eighty-six, Jansson produced paintings, novels, children’s books, magazine covers, political cartoons, greeting cards, librettos, and much more. But most of Jansson’s fans arrived by way of the Moomins, a friendly species of her invention—rotund white creatures that look a little like upright hippos, and were the subject of nine best-selling books and a daily comic strip that ran for twenty years.

Jansson travelled frequently to conduct her duties as the ambassador of Moominvalley, mingling at parties where businessmen wore Moomin ties.

more here.

On Anna Sewell’s ‘Black Beauty’

Karen Swallow Prior at Marginalia Review of Books:

It is perhaps partially owing to this plain style that Black Beauty is now classified as children’s literature. (But it is perhaps owing, too, to a modern day disdain for simple things like manual labor, animals, imagination, and kindness.) During the mid-Victorian era, children’s literature was a still-developing category of books. The fact is that Sewell was writing for men. And she was read by them, too, as one review attests: “Both men and boys read it with the greatest avidity, and many declare it to be ‘the best book in the world’.”

It is perhaps partially owing to this plain style that Black Beauty is now classified as children’s literature. (But it is perhaps owing, too, to a modern day disdain for simple things like manual labor, animals, imagination, and kindness.) During the mid-Victorian era, children’s literature was a still-developing category of books. The fact is that Sewell was writing for men. And she was read by them, too, as one review attests: “Both men and boys read it with the greatest avidity, and many declare it to be ‘the best book in the world’.”

While horse stories and talking animals are relegated today to children (especially girls), literary categories were less rigid then. So although the premise—a tale narrated by a horse—might seem childish to modern day readers, such a conceit was a novelty, edgy even, in its day.

more here.

How Genetic Mutations Turned the Coronavirus Deadly

Robert Bazell in Nautilus:

Long before the first reports of a new flu-like illness in China’s Hubei province, a bat—or perhaps a whole colony of them—was flying around the region carrying a new type of coronavirus. At the time, the virus was not yet dangerous to humans. Then, around the end of November, it underwent a slight additional mutation, evolving into the viral strain we now call SARS-CoV-2. With that flip of viral RNA, so began the COVID-19 pandemic. As in almost every outbreak, the mutations that set off this global crisis went undetected at first, even though the family of coronaviruses was already known to cause a variety of human diseases. “These viruses have long been understudied and have not been given the attention or funding they have deserved,” Craig Wilen, a virologist at Yale University, told me.

Long before the first reports of a new flu-like illness in China’s Hubei province, a bat—or perhaps a whole colony of them—was flying around the region carrying a new type of coronavirus. At the time, the virus was not yet dangerous to humans. Then, around the end of November, it underwent a slight additional mutation, evolving into the viral strain we now call SARS-CoV-2. With that flip of viral RNA, so began the COVID-19 pandemic. As in almost every outbreak, the mutations that set off this global crisis went undetected at first, even though the family of coronaviruses was already known to cause a variety of human diseases. “These viruses have long been understudied and have not been given the attention or funding they have deserved,” Craig Wilen, a virologist at Yale University, told me.

A bat coronavirus caused the SARS outbreak that terrified much of the world and killed 774 people in 2002 and 2003 before it was contained. Since then, there have been regular flare-ups of Middle East respiratory Syndrome or MERS, caused by another bat coronavirus that passes through camels; since 2012, it has killed 884 people. Most research on potential pandemics nevertheless continued to focus on influenza viruses, such as bird flu, because they carry a significant annual death toll. COVID-19 is exposing the dangers of such a single-minded approach. A few scientists tried to sound the alarm. In a 2015 study, epidemiologist Ralph Baric and his colleagues at the University of North Carolina analyzed the genomes of bat coronaviruses and warned, “Our work suggests a potential risk of SARS-CoV re-emergence from viruses currently circulating in bat populations.”1 A second paper from the same group the next year warned that another SARS-like disease from bat coronaviruses was “poised for human emergence.”2 Bats are well known as a reservoir for potential new human diseases. The animals carry dozens, perhaps hundreds, of members of the coronavirus family. Most of those viruses are part of the bats’ normal microbiome, living in harmony with their hosts and causing no harm. But coronaviruses, like all forms of life, accumulate random genetic changes as they reproduce. Occasionally the mutations allow the viruses to infect other animals (including humans) and to score the big win in natural selection: producing ever-more descendants.

A win for the virus, that is. For us, not so much.

More here.

You’ve Got Mail. Will You Get the Coronavirus?

Nicola Twilley in The New York Times:

Scientists agree that the main means by which the SARS-CoV-2 virus jumps from an infected person to its next host is by hitching a ride in the tiny droplets that are sprayed into the air with each cough or sneeze. But with deliveries now at holiday levels as locked-down Americans shop online rather than in person, the question remains: Can you catch the coronavirus from the parcels and packages your overburdened mail carrier keeps leaving at your door? The first formal process for curbing the spread of infection by detaining travelers from an affected region until their health was proved was instituted in what is now Dubrovnik, Croatia, in 1377, against the bubonic plague. (This temporal buffer was originally 30 days, but when that proved too short, it was extended to 40 days, or quaranta giorni, from which we derive the word “quarantine.”)

Scientists agree that the main means by which the SARS-CoV-2 virus jumps from an infected person to its next host is by hitching a ride in the tiny droplets that are sprayed into the air with each cough or sneeze. But with deliveries now at holiday levels as locked-down Americans shop online rather than in person, the question remains: Can you catch the coronavirus from the parcels and packages your overburdened mail carrier keeps leaving at your door? The first formal process for curbing the spread of infection by detaining travelers from an affected region until their health was proved was instituted in what is now Dubrovnik, Croatia, in 1377, against the bubonic plague. (This temporal buffer was originally 30 days, but when that proved too short, it was extended to 40 days, or quaranta giorni, from which we derive the word “quarantine.”)

Mail disinfection soon followed, as the then Republic of Venice extended and formalized the quarantine process to include cargo. Items that were considered particularly susceptible, including textiles and letters, were also subject to fumigation: dipped in or sprinkled with vinegar, then often exposed to smoke from aromatic substances, from rosemary to, in later years, chlorine. Once the items were treated, a distinctive wax seal or cancellation was usually applied to them, so the recipient would know where and when the disinfection had been carried out. (Such marks often provide the only remaining evidence of the ebb and flow of disease; some minor outbreaks of plague or typhus in remote areas of medieval Europe, for example, would have been lost to history without their postal traces.) The diseases changed, but for centuries mail disinfection techniques remained largely the same. As recently as 1900, during a plague outbreak in Honolulu, letters were routinely disinfected by clipping off the two opposite corners of each envelope and then spreading a batch of mail out in an airtight room filled with sulfur fumes for three hours.

More here.