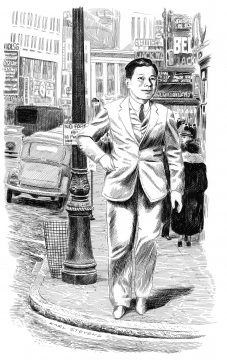

Ed Park in the New York Review of Books:

What if the finest, funniest, craziest, sanest, most cheerfully depressing Korean-American novel was also one of the first? To a modern reader, the most dated thing about Younghill Kang’s East Goes West, published by Scribner’s in 1937, is its tired title. (Either that or its subtitle, “The Making of an Oriental Yankee.”) Practically everything else about this brash modernist comic novel still feels electric.

East Goes West has a ghostly history: at times vaguely canonical, yet without discernible influence, it has been out of print for decades at a stretch, and surfaces every quarter-century or so as a sort of literary Brigadoon. (Last year’s Penguin Classics edition is its third major republication.) Kang’s debut, The Grass Roof (1931), captures the twilight of the Korean kingdom in the first two decades of the twentieth century, as Japan colonizes the peninsula. Its narrator, Chungpa Han, is a precocious child whose thirst for education takes him from his secluded home village to Seoul, three hundred miles away; into the heart of Japan; and finally to America, where East Goes West picks up on the pilgrim’s progress.

Though both novels were first published to great acclaim by Maxwell Perkins—the legendary editor of Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Thomas Wolfe—they stand as the alpha and omega of Kang’s fiction career: an explosion of talent, followed by thirty-five years of silence.

More here.

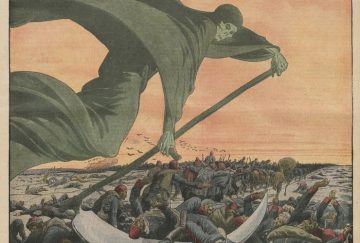

Fear sweeps the land. Many businesses collapse. Some huge fortunes are made. Panicked consumers stockpile paper, food, and weapons. The government’s reaction is inconsistent and ineffectual. Ordinary commerce grinds to a halt; investors can find no safe assets. Political factionalism grows more intense. Everything falls apart. This was all as true of revolutionary France in 1789 and 1790 as it is of the United States today. Are we at the beginning of a revolution that has yet to be named? Do we want to be? That we are on the verge of a major transformation seems obvious. The onset of the next Depression, a challenge akin to World War II, a

Fear sweeps the land. Many businesses collapse. Some huge fortunes are made. Panicked consumers stockpile paper, food, and weapons. The government’s reaction is inconsistent and ineffectual. Ordinary commerce grinds to a halt; investors can find no safe assets. Political factionalism grows more intense. Everything falls apart. This was all as true of revolutionary France in 1789 and 1790 as it is of the United States today. Are we at the beginning of a revolution that has yet to be named? Do we want to be? That we are on the verge of a major transformation seems obvious. The onset of the next Depression, a challenge akin to World War II, a  Over at the NYRB Blog, Ali Bhutto, Jamie Quatro, Edward Stephens, Carl Elliott, and Liza Batkin, et al.:

Over at the NYRB Blog, Ali Bhutto, Jamie Quatro, Edward Stephens, Carl Elliott, and Liza Batkin, et al.: Omar Shaban in Counterpunch:

Omar Shaban in Counterpunch:

Alex de Waal in Boston Review:

Alex de Waal in Boston Review: Over at NDPR, Allen Wood reviews Henry Allison’s Kant’s Conception of Freedom: A Developmental and Critical Analysis:

Over at NDPR, Allen Wood reviews Henry Allison’s Kant’s Conception of Freedom: A Developmental and Critical Analysis: What makes My Morningless Mornings so notable, though, is not just the story of a ruminative young person who rejects the thrills associated with teenage life or even the early onset of her adulthood. Golberg’s work also functions as an abstract, winding, and rebellious consideration of the mundane qualities of the day’s earliest hours. Whereas the morning often is referred to as a beginning or a renewal of possibilities, Golberg instead asks her readers to consider it night’s ending and the conclusion of dream-induced wanderings and endless darkness.

What makes My Morningless Mornings so notable, though, is not just the story of a ruminative young person who rejects the thrills associated with teenage life or even the early onset of her adulthood. Golberg’s work also functions as an abstract, winding, and rebellious consideration of the mundane qualities of the day’s earliest hours. Whereas the morning often is referred to as a beginning or a renewal of possibilities, Golberg instead asks her readers to consider it night’s ending and the conclusion of dream-induced wanderings and endless darkness. Two of my favorite essays, by Seamus Perry and Sandra Mayer respectively, offer guided tours of W.H. Auden’s apartment at 77 St. Mark’s Place in New York, where the poet lived between 1954 and 1972, and his late-in-life Kirchstetten house in Austria. Auden famously united minimum attention to his living conditions with maximum regard for routine and order. He wore the same suit day after day, padded around Manhattan in carpet slippers and utilized his kitchen sink as a toilet. Composer Igor Stravinsky called him “the dirtiest man I have ever liked.” Relying on literary journalism to pay his bills, Auden toiled at his desk every day from 9 a.m. till 4 or 5 p.m., then enjoyed a massive cocktail or two, sat down to a well prepared dinner promptly at 6 and toddled off to bed as early as 9:00, sometimes shooing guests out the door. In Austria, the poet acquired a yellow Volkswagen, eventually used as the getaway car in a series of robberies committed by a longtime lover.

Two of my favorite essays, by Seamus Perry and Sandra Mayer respectively, offer guided tours of W.H. Auden’s apartment at 77 St. Mark’s Place in New York, where the poet lived between 1954 and 1972, and his late-in-life Kirchstetten house in Austria. Auden famously united minimum attention to his living conditions with maximum regard for routine and order. He wore the same suit day after day, padded around Manhattan in carpet slippers and utilized his kitchen sink as a toilet. Composer Igor Stravinsky called him “the dirtiest man I have ever liked.” Relying on literary journalism to pay his bills, Auden toiled at his desk every day from 9 a.m. till 4 or 5 p.m., then enjoyed a massive cocktail or two, sat down to a well prepared dinner promptly at 6 and toddled off to bed as early as 9:00, sometimes shooing guests out the door. In Austria, the poet acquired a yellow Volkswagen, eventually used as the getaway car in a series of robberies committed by a longtime lover. The window was sealed behind a sheet of solid steel. The door was locked. Thick chains bound one arm and one ankle. The room was bare apart from a thin foam mat for a bed and a plastic bottle to pee into. I was alone. That was the summer of 1987, when Hizbullah was holding me hostage in Lebanon. They had many other hostages, but I didn’t see them. In fact, I saw no one. When a guard came into the room, I had to put on a blindfold so that I couldn’t identify him. The only conversations I had were a few interrogations, when I was also blindfolded. The questioning involved threats and verbal abuse, but mercifully no torture. As unpleasant as they were, they broke the monotony. The rest of the time left me thinking, remembering, imagining. One way of relieving the loneliness was to pretend that one or another of my children was with me, each on a different day. I made chess pieces out of paper labels on water bottles to play with each one. Sometimes I let them win, or they beat me outright.

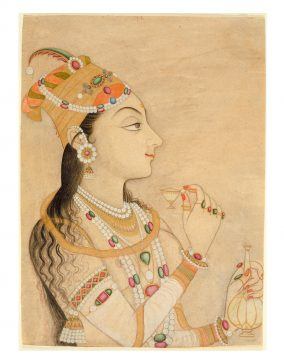

The window was sealed behind a sheet of solid steel. The door was locked. Thick chains bound one arm and one ankle. The room was bare apart from a thin foam mat for a bed and a plastic bottle to pee into. I was alone. That was the summer of 1987, when Hizbullah was holding me hostage in Lebanon. They had many other hostages, but I didn’t see them. In fact, I saw no one. When a guard came into the room, I had to put on a blindfold so that I couldn’t identify him. The only conversations I had were a few interrogations, when I was also blindfolded. The questioning involved threats and verbal abuse, but mercifully no torture. As unpleasant as they were, they broke the monotony. The rest of the time left me thinking, remembering, imagining. One way of relieving the loneliness was to pretend that one or another of my children was with me, each on a different day. I made chess pieces out of paper labels on water bottles to play with each one. Sometimes I let them win, or they beat me outright. Thomas Roe, Britain’s envoy in India during the 1620s, wrote of Empress Nur Jehan’s power over her husband, the Mughal emperor Jehangir, that she “governs him, and wynds him up at her pleasure.”

Thomas Roe, Britain’s envoy in India during the 1620s, wrote of Empress Nur Jehan’s power over her husband, the Mughal emperor Jehangir, that she “governs him, and wynds him up at her pleasure.”