If the River Was Whiskey,

If I Was a Duck

If our Phrenes, when fusty, could take the waters,

Head to Baden-Baden, play the tables and come

Home fresh, or, infused with saffron, spritzed with anise,

Return as cocktail-drinking cocktails; if the World

Wide Web was Roxy Music; if we were Eno

Seated at a VCS3, helmsman of time’s

Own ship, ever drifting into port, then yeah—I’d

Dive to the bottom too. But they’re not, and it’s not,

And we’re not, and only a god can save us, not

Cybernetics or Gold Bond Cream. For we are the

Bomb, not in the sense of cool, as we used to say

Or still say ironically, but The Bomb, the pearls

We sold regained, only now they’re sad peppercorns

That pull us down like bottles falling into front-

End loaders at 4 a.m. But things hold fast, sure

Us, whether through analogues or discretely, that

Existence is not just some hemispherical

Container filled with drupes, but life, the voice of Bing

Crosby, patience, yes, a true bowl of cherries, a

Question ripe and there as William Williams’s plums

by Robert Farrell

from Narrative Magazine

Of all the resources lacking in the Covid-19 pandemic, the one most desperately needed in the United States is a unified national strategy, as well as the confident, coherent and consistent leadership to see it carried out. The country cannot go from one mixed-message news briefing to the next, and from tweet to tweet, to define policy priorities. It needs a science-based plan that looks to the future rather than merely reacting to latest turn in the crisis.

Of all the resources lacking in the Covid-19 pandemic, the one most desperately needed in the United States is a unified national strategy, as well as the confident, coherent and consistent leadership to see it carried out. The country cannot go from one mixed-message news briefing to the next, and from tweet to tweet, to define policy priorities. It needs a science-based plan that looks to the future rather than merely reacting to latest turn in the crisis. What direction does time point in? None, really, although some people might subconsciously put the past on the left and the future on the right, or the past behind themselves and the future in front, or many other possible orientations. What feels natural to you depends in large degree on the native language you speak, and how it talks about time. This is a clue to a more general phenomenon, how language shapes the way we think. Lera Boroditsky is one of the world’s experts on this phenomenon. She uses how different languages construe time and space (as well as other things) to help tease out the way our brains make sense of the world.

What direction does time point in? None, really, although some people might subconsciously put the past on the left and the future on the right, or the past behind themselves and the future in front, or many other possible orientations. What feels natural to you depends in large degree on the native language you speak, and how it talks about time. This is a clue to a more general phenomenon, how language shapes the way we think. Lera Boroditsky is one of the world’s experts on this phenomenon. She uses how different languages construe time and space (as well as other things) to help tease out the way our brains make sense of the world. Defeating Covid-19 will call for more than vaccines; it will involve quarantines, social distancing, antivirals and other drugs, and healthcare for the sick. But the idea of a vaccine – the quintessential silver bullet – has come to bear an almost unreasonable allure. The coronavirus arrived at a ripe moment in genetic technology, when the advances of the past half-decade have made it possible for vaccine projects to explode off the blocks as soon as a virus is sequenced. These cutting-edge vaccines don’t use weakened forms of the germ to build our immunity, as all vaccines once did; rather, they contain short copies of parts of the germ’s genetic code – its DNA or RNA – which can produce fragments of the germ within our bodies.

Defeating Covid-19 will call for more than vaccines; it will involve quarantines, social distancing, antivirals and other drugs, and healthcare for the sick. But the idea of a vaccine – the quintessential silver bullet – has come to bear an almost unreasonable allure. The coronavirus arrived at a ripe moment in genetic technology, when the advances of the past half-decade have made it possible for vaccine projects to explode off the blocks as soon as a virus is sequenced. These cutting-edge vaccines don’t use weakened forms of the germ to build our immunity, as all vaccines once did; rather, they contain short copies of parts of the germ’s genetic code – its DNA or RNA – which can produce fragments of the germ within our bodies. In response to the swiftly escalating COVID-19 epidemic, whole countries are

In response to the swiftly escalating COVID-19 epidemic, whole countries are  As hundreds of millions of people, maybe billions, avoid social contact to spare themselves and their communities from coronavirus, researchers are discussing a dramatic approach to research that could help end the pandemic: infecting a handful of healthy volunteers with the virus to rapidly test a vaccine. Many scientists see a vaccine as the only solution to the pandemic. Clinical safety trials began this month for one candidate vaccine, and others will soon follow. But one of the biggest hurdles will be showing that a vaccine works. Typically, this is done through large phase III studies, in which thousands to tens of thousands of people receive either a vaccine or a placebo, and researchers track who becomes infected in the course of their daily lives. A quicker option would be to conduct a ‘human challenge’ study, argue scientists in a provocative preprint published this week

As hundreds of millions of people, maybe billions, avoid social contact to spare themselves and their communities from coronavirus, researchers are discussing a dramatic approach to research that could help end the pandemic: infecting a handful of healthy volunteers with the virus to rapidly test a vaccine. Many scientists see a vaccine as the only solution to the pandemic. Clinical safety trials began this month for one candidate vaccine, and others will soon follow. But one of the biggest hurdles will be showing that a vaccine works. Typically, this is done through large phase III studies, in which thousands to tens of thousands of people receive either a vaccine or a placebo, and researchers track who becomes infected in the course of their daily lives. A quicker option would be to conduct a ‘human challenge’ study, argue scientists in a provocative preprint published this week Jake Wojtowicz in Aeon:

Jake Wojtowicz in Aeon: Christopher Mackin in TNR:

Christopher Mackin in TNR: David Runciman in The Guardian:

David Runciman in The Guardian:

People around the world are processing the news that the revered spiritual leader

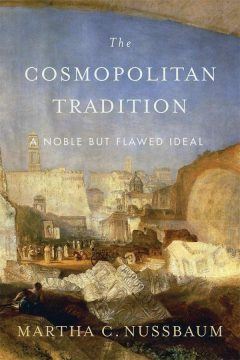

People around the world are processing the news that the revered spiritual leader  LIKE MARTHA NUSSBAUM’S other books, The Cosmopolitan Tradition is a profound and insightful interrogation of central issues in philosophy and our everyday lives. Nussbaum’s newest contribution analyzes the “Cosmopolitan tradition” — that is, the view that we are citizens of the world who enjoy the equal and unconditional worth of all human beings. This worth is independent of people’s individual traits, which depend on fortuitous natural or social arrangements. As Nussbaum claims, the “insight that politics ought to treat human beings both as equal and as having a worth beyond price is one of the deepest and most influential insights of Western thought.” She further argues that, in this tradition, dignity — the right of a person to be treated respectfully for her own sake — is non-hierarchical. It belongs, in equal measure, to all who have some basic threshold capacity for moral learning and choice. Nussbaum persuasively argues that the major flaw of this noble idea is the bifurcation between duties of justice, on the one hand, and duties of material expenditure, on the other.

LIKE MARTHA NUSSBAUM’S other books, The Cosmopolitan Tradition is a profound and insightful interrogation of central issues in philosophy and our everyday lives. Nussbaum’s newest contribution analyzes the “Cosmopolitan tradition” — that is, the view that we are citizens of the world who enjoy the equal and unconditional worth of all human beings. This worth is independent of people’s individual traits, which depend on fortuitous natural or social arrangements. As Nussbaum claims, the “insight that politics ought to treat human beings both as equal and as having a worth beyond price is one of the deepest and most influential insights of Western thought.” She further argues that, in this tradition, dignity — the right of a person to be treated respectfully for her own sake — is non-hierarchical. It belongs, in equal measure, to all who have some basic threshold capacity for moral learning and choice. Nussbaum persuasively argues that the major flaw of this noble idea is the bifurcation between duties of justice, on the one hand, and duties of material expenditure, on the other. There is a box in my apartment labeled “Old Not Good Photos.” This is an understatement. Most of the photos are two-and-a-half-inch squares, showing little blurred black-and-white images, taken from too far away of people whose features you can barely make out, standing or sitting alone or in groups, against backgrounds of gray uninterestingness. They are like the barely flickering dreams that dissipate as we awaken, rather than the self-important ones that follow us into the day and seem to be crying out for interpretation. However, as psychoanalysis has taught us, it is the least prepossessing dreams, disguised as such to put us off the scent, that sometimes bear the most important messages from inner life. So too, some of the drab little photographs, if stared at long enough, begin to speak to us.

There is a box in my apartment labeled “Old Not Good Photos.” This is an understatement. Most of the photos are two-and-a-half-inch squares, showing little blurred black-and-white images, taken from too far away of people whose features you can barely make out, standing or sitting alone or in groups, against backgrounds of gray uninterestingness. They are like the barely flickering dreams that dissipate as we awaken, rather than the self-important ones that follow us into the day and seem to be crying out for interpretation. However, as psychoanalysis has taught us, it is the least prepossessing dreams, disguised as such to put us off the scent, that sometimes bear the most important messages from inner life. So too, some of the drab little photographs, if stared at long enough, begin to speak to us. On 29 August 1966, the Beatles closed their set at the Candlestick Park baseball stadium in San Francisco with “Long Tall Sally”, an old Little Richard number that had been part of their repertoire from the very start. “See you again next year,” said John as they left the stage. The group then clambered into an armoured car and were driven away. It was to be their last proper concert. Their American tour had been exhausting, sporadically frightening, and unrewarding. By this stage their delight in their own fame had worn off. They were fed up with all the hassle of touring, and tired of the way the screaming continued to drown out the music, so that even they were unable to hear it. Having been shepherded into an empty, windowless truck after a particularly miserable show in a rainy St Louis, Paul said to the others: “I really fucking agree with you. I’ve fucking had it up to here too.”

On 29 August 1966, the Beatles closed their set at the Candlestick Park baseball stadium in San Francisco with “Long Tall Sally”, an old Little Richard number that had been part of their repertoire from the very start. “See you again next year,” said John as they left the stage. The group then clambered into an armoured car and were driven away. It was to be their last proper concert. Their American tour had been exhausting, sporadically frightening, and unrewarding. By this stage their delight in their own fame had worn off. They were fed up with all the hassle of touring, and tired of the way the screaming continued to drown out the music, so that even they were unable to hear it. Having been shepherded into an empty, windowless truck after a particularly miserable show in a rainy St Louis, Paul said to the others: “I really fucking agree with you. I’ve fucking had it up to here too.”