Jill Lepore in The New Yorker:

When the plague came to London in 1665, Londoners lost their wits. They consulted astrologers, quacks, the Bible. They searched their bodies for signs, tokens of the disease: lumps, blisters, black spots. They begged for prophecies; they paid for predictions; they prayed; they yowled. They closed their eyes; they covered their ears. They wept in the street. They read alarming almanacs: “Certain it is, books frighted them terribly.” The government, keen to contain the panic, attempted “to suppress the Printing of such Books as terrify’d the People,” according to Daniel Defoe, in “A Journal of the Plague Year,” a history that he wrote in tandem with an advice manual called “Due Preparations for the Plague,” in 1722, a year when people feared that the disease might leap across the English Channel again, after having journeyed from the Middle East to Marseille and points north on a merchant ship. Defoe hoped that his books would be useful “both to us and to posterity, though we should be spared from that portion of this bitter cup.” That bitter cup has come out of its cupboard.

When the plague came to London in 1665, Londoners lost their wits. They consulted astrologers, quacks, the Bible. They searched their bodies for signs, tokens of the disease: lumps, blisters, black spots. They begged for prophecies; they paid for predictions; they prayed; they yowled. They closed their eyes; they covered their ears. They wept in the street. They read alarming almanacs: “Certain it is, books frighted them terribly.” The government, keen to contain the panic, attempted “to suppress the Printing of such Books as terrify’d the People,” according to Daniel Defoe, in “A Journal of the Plague Year,” a history that he wrote in tandem with an advice manual called “Due Preparations for the Plague,” in 1722, a year when people feared that the disease might leap across the English Channel again, after having journeyed from the Middle East to Marseille and points north on a merchant ship. Defoe hoped that his books would be useful “both to us and to posterity, though we should be spared from that portion of this bitter cup.” That bitter cup has come out of its cupboard.

In 1665, the skittish fled to the country, and alike the wise, and those who tarried had reason for remorse: by the time they decided to leave, “there was hardly a Horse to be bought or hired in the whole City,” Defoe recounted, and, in the event, the gates had been shut, and all were trapped. Everyone behaved badly, though the rich behaved the worst: having failed to heed warnings to provision, they sent their poor servants out for supplies. “This Necessity of going out of our Houses to buy Provisions, was in a great Measure the Ruin of the whole City,” Defoe wrote. One in five Londoners died, notwithstanding the precautions taken by merchants. The butcher refused to hand the cook a cut of meat; she had to take it off the hook herself. And he wouldn’t touch her money; she had to drop her coins into a bucket of vinegar. Bear that in mind when you run out of Purell.

“Sorrow and sadness sat upon every Face,” Defoe wrote. The government’s stricture on the publication of terrifying books proved pointless, there being plenty of terror to be read on the streets. You could read the weekly bills of mortality, or count the bodies as they piled up in the lanes. You could read the orders published by the mayor: “If any Person shall have visited any Man known to be infected of the Plague, or entered willingly into any known infected House, being not allowed: The House wherein he inhabiteth shall be shut up.” And you could read the signs on the doors of those infected houses, guarded by watchmen, each door marked by a foot-long red cross, above which was to be printed, in letters big enough to be read at a distance, “Lord, Have Mercy Upon Us.”

More here.

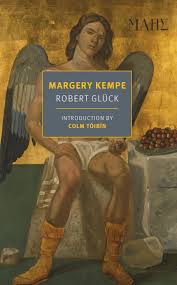

The cumulative strength of the New Narrative, which consisted of a core group of writers who took government-funded workshops run by Glück and the similarly under-sung Bruce Boone as well as some kindred, famous spirits far from Northern California—Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper, Gary Indiana, and Chris Kraus—ensured that Glück’s name has remained in certain corners of the American literary edifice over the past few decades. Yet time and a shifting sensibility has relegated his own fiction to creaky personal libraries such as my own. I crack open original editions of Jack the Modernist and Margery Kempe and see the names of lost, idealistic imprints, SeaHorse and High Risk Books, which went down with the sinking ship of American publishing while larger houses bought space on the lifeboats. The paper trail of gay literature—put out by presses little and big—is inherently splotchy: so many people who had reason to remember died of AIDS.

The cumulative strength of the New Narrative, which consisted of a core group of writers who took government-funded workshops run by Glück and the similarly under-sung Bruce Boone as well as some kindred, famous spirits far from Northern California—Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper, Gary Indiana, and Chris Kraus—ensured that Glück’s name has remained in certain corners of the American literary edifice over the past few decades. Yet time and a shifting sensibility has relegated his own fiction to creaky personal libraries such as my own. I crack open original editions of Jack the Modernist and Margery Kempe and see the names of lost, idealistic imprints, SeaHorse and High Risk Books, which went down with the sinking ship of American publishing while larger houses bought space on the lifeboats. The paper trail of gay literature—put out by presses little and big—is inherently splotchy: so many people who had reason to remember died of AIDS.

It is not surprising to find Rusty Reno, editor of First Things,

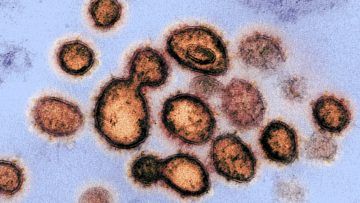

It is not surprising to find Rusty Reno, editor of First Things,  Drugs that slow or kill the novel coronavirus, called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), could save the lives of severely ill patients, but might also be given prophylactically to protect health care workers and others at high risk of infection. Treatments may also reduce the time patients spend in intensive care units, freeing critical hospital beds. Scientists have suggested dozens of existing compounds for testing, but WHO is focusing on what it says are the four most promising therapies: an experimental antiviral compound called remdesivir; the malaria medications chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine; a combination of two HIV drugs, lopinavir and ritonavir; and that same combination plus interferon-beta, an immune system messenger that can help cripple viruses. Some data on their use in COVID-19 patients have already emerged—the HIV combo failed in a small study in China—but WHO believes a large trial with a greater variety of patients is warranted.

Drugs that slow or kill the novel coronavirus, called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), could save the lives of severely ill patients, but might also be given prophylactically to protect health care workers and others at high risk of infection. Treatments may also reduce the time patients spend in intensive care units, freeing critical hospital beds. Scientists have suggested dozens of existing compounds for testing, but WHO is focusing on what it says are the four most promising therapies: an experimental antiviral compound called remdesivir; the malaria medications chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine; a combination of two HIV drugs, lopinavir and ritonavir; and that same combination plus interferon-beta, an immune system messenger that can help cripple viruses. Some data on their use in COVID-19 patients have already emerged—the HIV combo failed in a small study in China—but WHO believes a large trial with a greater variety of patients is warranted. Though mild, I have what I am fairly sure are the symptoms of coronavirus. Three weeks ago I was in extended and close contact with someone who has since tested positive. When I learned this, I spent some time trying to figure out how to get tested myself, but now the last thing I want to do is to go stand in a line in front of a Brooklyn hospital along with others who also have symptoms. My wife and I have not been outside our apartment since March 10th. We have opened the door just three times since then, to receive groceries that had been left for us by an unseen deliveryman, as per our instructions, on the other side. We read of others going on walks, but that seems like a selfish extravagance when you have a dry cough and a sore throat. This is the smallest apartment I’ve ever lived in. I am noticing features of it, and of the trees, the sky and the light outside our windows, that escaped my attention—shamefully, it now seems—over the first several months since we arrived here in August. I know when we finally get out I will be like the protagonist of Halldór Laxness’s stunning novel, World Light, who, after years of bedridden illness, weeps when he bids farewell to all the knots and grooves in the wood beams of his attic ceiling.

Though mild, I have what I am fairly sure are the symptoms of coronavirus. Three weeks ago I was in extended and close contact with someone who has since tested positive. When I learned this, I spent some time trying to figure out how to get tested myself, but now the last thing I want to do is to go stand in a line in front of a Brooklyn hospital along with others who also have symptoms. My wife and I have not been outside our apartment since March 10th. We have opened the door just three times since then, to receive groceries that had been left for us by an unseen deliveryman, as per our instructions, on the other side. We read of others going on walks, but that seems like a selfish extravagance when you have a dry cough and a sore throat. This is the smallest apartment I’ve ever lived in. I am noticing features of it, and of the trees, the sky and the light outside our windows, that escaped my attention—shamefully, it now seems—over the first several months since we arrived here in August. I know when we finally get out I will be like the protagonist of Halldór Laxness’s stunning novel, World Light, who, after years of bedridden illness, weeps when he bids farewell to all the knots and grooves in the wood beams of his attic ceiling. I had a bone marrow transplant in 2017. Most people don’t really know what that is. In the simplest possible terms, it means that my doctors gave me a new immune system, by replacing my sick bone marrow with healthy bone marrow from my sister.

I had a bone marrow transplant in 2017. Most people don’t really know what that is. In the simplest possible terms, it means that my doctors gave me a new immune system, by replacing my sick bone marrow with healthy bone marrow from my sister. Bill Gates rebuked proposals, floated over the last two days by leaders like Donald Trump, to reopen the global economy despite

Bill Gates rebuked proposals, floated over the last two days by leaders like Donald Trump, to reopen the global economy despite  It happened slowly and then suddenly. On Monday, March 9th, the spectre of a pandemic in New York was still off on the puzzling horizon. By Friday, it was the dominant fact of life. New Yorkers began to adopt a grim new dance of “social distancing.” On a sparsely peopled 5 train, heading down to Grand Central Terminal on Saturday morning, passengers warily tried to achieve an even, strategic spacing, like chess pieces during an endgame: the rook all the way down here, but threatening the king from the back row. Then, when the doors opened, they got off the train one by one, in single, hesitant file, unlearning in a minute New York habits ingrained over lifetimes, the elbowed rush for the door. In the relatively empty subway cars, one can focus on the human details of the riders. A. J. Liebling, in a piece published in these pages some sixty years ago, recounted the tale of a once famous New York murder, in which the headless torso of a man was found wrapped in oilcloth, floating in the East River. The hero of the tale, as Liebling chose to tell it, was a young reporter for the great New York World, who identified the body by type before anyone else did: he saw that the corpse’s fingertips were wrinkled in a way that characterized “rubbers”—masseurs—in Turkish baths. Only someone whose hands were wet that often would have those fingertips. On the subway, in the street, nearly everyone has rubbers’ hands now, with skin shrivelled from excessive washing.

It happened slowly and then suddenly. On Monday, March 9th, the spectre of a pandemic in New York was still off on the puzzling horizon. By Friday, it was the dominant fact of life. New Yorkers began to adopt a grim new dance of “social distancing.” On a sparsely peopled 5 train, heading down to Grand Central Terminal on Saturday morning, passengers warily tried to achieve an even, strategic spacing, like chess pieces during an endgame: the rook all the way down here, but threatening the king from the back row. Then, when the doors opened, they got off the train one by one, in single, hesitant file, unlearning in a minute New York habits ingrained over lifetimes, the elbowed rush for the door. In the relatively empty subway cars, one can focus on the human details of the riders. A. J. Liebling, in a piece published in these pages some sixty years ago, recounted the tale of a once famous New York murder, in which the headless torso of a man was found wrapped in oilcloth, floating in the East River. The hero of the tale, as Liebling chose to tell it, was a young reporter for the great New York World, who identified the body by type before anyone else did: he saw that the corpse’s fingertips were wrinkled in a way that characterized “rubbers”—masseurs—in Turkish baths. Only someone whose hands were wet that often would have those fingertips. On the subway, in the street, nearly everyone has rubbers’ hands now, with skin shrivelled from excessive washing. Hospitals in New York City are gearing up to use the blood of people who have recovered from COVID-19 as a possible antidote for the disease. Researchers hope that the century-old approach of infusing patients with the antibody-laden blood of those who have survived an infection will help the metropolis — now the US epicentre of the outbreak — to avoid the fate of Italy, where intensive-care units (ICUs) are so crowded that doctors have turned away patients who need ventilators to breathe. The efforts follow studies in China that attempted the measure with plasma — the fraction of blood that contains antibodies, but not red blood cells — from people who had recovered from COVID-19. But these studies have reported only preliminary results so far. The convalescent plasma approach has also seen modest success during past severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Ebola outbreaks — but US researchers are hoping to increase the value of the treatment by selecting donor blood that is packed with antibodies and giving it to the patients who are most likely to benefit.

Hospitals in New York City are gearing up to use the blood of people who have recovered from COVID-19 as a possible antidote for the disease. Researchers hope that the century-old approach of infusing patients with the antibody-laden blood of those who have survived an infection will help the metropolis — now the US epicentre of the outbreak — to avoid the fate of Italy, where intensive-care units (ICUs) are so crowded that doctors have turned away patients who need ventilators to breathe. The efforts follow studies in China that attempted the measure with plasma — the fraction of blood that contains antibodies, but not red blood cells — from people who had recovered from COVID-19. But these studies have reported only preliminary results so far. The convalescent plasma approach has also seen modest success during past severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Ebola outbreaks — but US researchers are hoping to increase the value of the treatment by selecting donor blood that is packed with antibodies and giving it to the patients who are most likely to benefit. I personally believe we will blunt this epidemic, but I think we wasted a good four to six weeks largely because of lack of testing and lack of a certain preparedness. But I think we could still make a difference and bring it under control with very harsh measures.

I personally believe we will blunt this epidemic, but I think we wasted a good four to six weeks largely because of lack of testing and lack of a certain preparedness. But I think we could still make a difference and bring it under control with very harsh measures. As the subtitle of this collection of essays plainly implies, Barnes did modernism her way. She might have been ambivalent about the movement, resulting in what Daniela Caselli calls her “aesthetics of uncertainty”. But there is no doubting her credentials as a modernist mover and shaker: as a Left Bank journalist, an interviewer of James Joyce, the author of that late modernist masterpiece Nightwood (1936) and the beneficiary of Peggy Guggenheim’s largesse. Yet Barnes also slips away from easy chronology and canonization, not least because of her longevity. Born in 1892, she died in 1982, at the age of ninety, having outlived many of her peers by decades. On its dust jacket and between chapters, Shattered Objects acknowledges that longevity by featuring photographs of her in later life. The visual representation matters. Barnes’s reputation has long been framed as a story of decline – as that of a once dazzling author turned (by the mid-century) recluse.

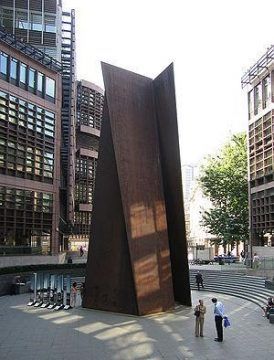

As the subtitle of this collection of essays plainly implies, Barnes did modernism her way. She might have been ambivalent about the movement, resulting in what Daniela Caselli calls her “aesthetics of uncertainty”. But there is no doubting her credentials as a modernist mover and shaker: as a Left Bank journalist, an interviewer of James Joyce, the author of that late modernist masterpiece Nightwood (1936) and the beneficiary of Peggy Guggenheim’s largesse. Yet Barnes also slips away from easy chronology and canonization, not least because of her longevity. Born in 1892, she died in 1982, at the age of ninety, having outlived many of her peers by decades. On its dust jacket and between chapters, Shattered Objects acknowledges that longevity by featuring photographs of her in later life. The visual representation matters. Barnes’s reputation has long been framed as a story of decline – as that of a once dazzling author turned (by the mid-century) recluse. When you look at the work of an artist like Richard Serra, or better yet, stand next to a classic Serra piece, you begin to understand how important the physical problem of balance and uprightness is for contemporary sculpture. Take one such classic work, Fulcrum (1987). The work consists of five fifty-five-foot tall slabs of COR-TEN steel. It dominates one of the entrances to the Liverpool Street station in London. Standing next to Fulcrum can be genuinely scary, all the more so when (and if) you realize that the huge slabs of steel are balanced one against the other simply by weight and angle. So, these slabs of steel can, theoretically, kill you. In fact, Serra’s sculptures have killed before and might do so again. Serra’s Sculpture No. 3 famously ended the life of a rigger named Raymond Johnson, who was crushed by it during installation at the Walker Art Center in 1977.

When you look at the work of an artist like Richard Serra, or better yet, stand next to a classic Serra piece, you begin to understand how important the physical problem of balance and uprightness is for contemporary sculpture. Take one such classic work, Fulcrum (1987). The work consists of five fifty-five-foot tall slabs of COR-TEN steel. It dominates one of the entrances to the Liverpool Street station in London. Standing next to Fulcrum can be genuinely scary, all the more so when (and if) you realize that the huge slabs of steel are balanced one against the other simply by weight and angle. So, these slabs of steel can, theoretically, kill you. In fact, Serra’s sculptures have killed before and might do so again. Serra’s Sculpture No. 3 famously ended the life of a rigger named Raymond Johnson, who was crushed by it during installation at the Walker Art Center in 1977. Raza argues that we have made little progress in fighting cancer over the last 50 years. The tools available to oncologists haven’t changed much–the bulk of the progress that has been made has been through earlier and earlier detection rather than more effective or compassionate treatment options. Raza wants to see a different approach from the current strategy of marginal improvements on narrowly defined problems at the cellular level. Instead, she suggests an alternative approach that might better take account of the complexity of human beings and the way that cancer morphs and spreads differently across people and even within individuals. The conversation includes the challenges of dealing with dying patients, the importance of listening, and the bittersweet nature of our mortality.

Raza argues that we have made little progress in fighting cancer over the last 50 years. The tools available to oncologists haven’t changed much–the bulk of the progress that has been made has been through earlier and earlier detection rather than more effective or compassionate treatment options. Raza wants to see a different approach from the current strategy of marginal improvements on narrowly defined problems at the cellular level. Instead, she suggests an alternative approach that might better take account of the complexity of human beings and the way that cancer morphs and spreads differently across people and even within individuals. The conversation includes the challenges of dealing with dying patients, the importance of listening, and the bittersweet nature of our mortality. Those young movie nuts would launch the French New Wave, along with Rohmer, who was its virtual godfather; yet it took him two decades to put his ideas into practice. What made the difference for this group’s movies was a new mode of production—scant budget, small crew, rapid shooting. For Rohmer, these methods helped him fuse his way of filming with his way of living—and

Those young movie nuts would launch the French New Wave, along with Rohmer, who was its virtual godfather; yet it took him two decades to put his ideas into practice. What made the difference for this group’s movies was a new mode of production—scant budget, small crew, rapid shooting. For Rohmer, these methods helped him fuse his way of filming with his way of living—and  To most people, the assertion that we are living in Skinner boxes might sound alarming, but The Age of Surveillance Capitalism goes darker still. Skinner, at least, saw himself as a do-gooder who would save humanity from its own delusions. His behavioral engineering was meant to build a happier humanity, one finally at peace with our lack of agency. “What is love,” Skinner wrote, “except another name for the use of positive reinforcement?”

To most people, the assertion that we are living in Skinner boxes might sound alarming, but The Age of Surveillance Capitalism goes darker still. Skinner, at least, saw himself as a do-gooder who would save humanity from its own delusions. His behavioral engineering was meant to build a happier humanity, one finally at peace with our lack of agency. “What is love,” Skinner wrote, “except another name for the use of positive reinforcement?” When the plague came to London in 1665, Londoners lost their wits. They consulted astrologers, quacks, the Bible. They searched their bodies for signs, tokens of the disease: lumps, blisters, black spots. They begged for prophecies; they paid for predictions; they prayed; they yowled. They closed their eyes; they covered their ears. They wept in the street. They read alarming almanacs: “Certain it is, books frighted them terribly.” The government, keen to contain the panic, attempted “to suppress the Printing of such Books as terrify’d the People,” according to Daniel Defoe, in “A Journal of the Plague Year,” a history that he wrote in tandem with an advice manual called “Due Preparations for the Plague,” in 1722, a year when people feared that the disease might leap across the English Channel again, after having journeyed from the Middle East to Marseille and points north on a merchant ship. Defoe hoped that his books would be useful “both to us and to posterity, though we should be spared from that portion of this bitter cup.” That bitter cup has come out of its cupboard.

When the plague came to London in 1665, Londoners lost their wits. They consulted astrologers, quacks, the Bible. They searched their bodies for signs, tokens of the disease: lumps, blisters, black spots. They begged for prophecies; they paid for predictions; they prayed; they yowled. They closed their eyes; they covered their ears. They wept in the street. They read alarming almanacs: “Certain it is, books frighted them terribly.” The government, keen to contain the panic, attempted “to suppress the Printing of such Books as terrify’d the People,” according to Daniel Defoe, in “A Journal of the Plague Year,” a history that he wrote in tandem with an advice manual called “Due Preparations for the Plague,” in 1722, a year when people feared that the disease might leap across the English Channel again, after having journeyed from the Middle East to Marseille and points north on a merchant ship. Defoe hoped that his books would be useful “both to us and to posterity, though we should be spared from that portion of this bitter cup.” That bitter cup has come out of its cupboard.