Dave Itzkoff in The New York Times:

When he set out to investigate the inner world of exotic animal breeders, Eric Goode had no idea he would end up making the hit Netflix series “Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness.”

When he set out to investigate the inner world of exotic animal breeders, Eric Goode had no idea he would end up making the hit Netflix series “Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness.”

Released less than two weeks ago, the series is already a sensation, immersing viewers in the lives and rivalries of vivid subjects like Bhagavan Antle, known as Doc, the bombastic proprietor of an animal preserve and safari tour in Myrtle Beach, S.C., and Carole Baskin, an animal activist and sanctuary owner in Tampa, Fla., whose former husband disappeared in 1997. And then, of course, there’s the Tiger King himself, Joseph Maldonado-Passage, better known as Joe Exotic, a flamboyant Oklahoma zookeeper, political candidate and aspiring celebrity who was sentenced in January to 22 years in prison for his involvement in a failed plot to kill Baskin and for killing five tiger cubs. Goode, who directed “Tiger King” with Rebecca Chaiklin, said that he had been reasonably confident the series would be successful. “How can you not be fascinated with polygamy, drugs, cults, tigers, potential murder?” Goode said in an interview on Tuesday. “It had all the ingredients that one finds salacious. So we knew that there would be an appetite for it.”

But he could hardly have suspected that “Tiger King” would arrive during the coronavirus pandemic, during which audiences have had ample time to pore over its jaw-dropping plot twists while they shelter in their homes. For some viewers, “Tiger King” has also been an introduction to Goode, 62, a founder of the fabled 1980s-era New York nightspot Area who is now an owner of downtown Manhattan establishments like the Bowery Hotel and the Waverly Inn. In an interview, Chaiklin said she first worked for Goode in the mid 1990s as a door girl and manager at the Bowery Bar and Grill. More recently, over a “crazy posh dinner,” Goode first told her about the wild kingdoms they would end up traveling together.

More here.

Imagine you are in a small boat far, far from shore. A surprise storm capsizes the boat and tosses you into the sea. You try to tame your panic, somehow find the boat’s flimsy but still floating life raft, and struggle into it. You catch your breath, look around, and try to think what to do next. Thinking clearly is hard to do after a near-drowning experience.

Imagine you are in a small boat far, far from shore. A surprise storm capsizes the boat and tosses you into the sea. You try to tame your panic, somehow find the boat’s flimsy but still floating life raft, and struggle into it. You catch your breath, look around, and try to think what to do next. Thinking clearly is hard to do after a near-drowning experience.

On autopsy, the brain of an Alzheimer’s patient can weigh as little as 30 percent of a healthy brain. The tissue grows porous. It is a sieve through which the past slips. As her mother loses her grasp on their shared history, Elizabeth Kadetsky sifts through boxes of the snapshots, newspaper clippings, pamphlets, and notebooks that remain, hoping to uncover the memories that her mother is actively losing as her dementia progresses. These remnants offer the false yet beguiling suggestion that the past is easy to reconstruct—easy to hold. At turns lyrical, poignant, and alluring, The Memory Eaters tells the story of a family’s cyclical and intergenerational incidents of trauma, secret-keeping, and forgetting in the context of the 1970s and 1980s New York City. Moving from her parents’ divorce to her mother’s career as a Seventh Avenue fashion model and from her sister’s addiction and homelessness to her own experiences with therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder, Kadetsky takes readers on a spiraling trip through memory, consciousness fractured by addiction and dementia, and a compulsion for the past salved by nostalgia.

On autopsy, the brain of an Alzheimer’s patient can weigh as little as 30 percent of a healthy brain. The tissue grows porous. It is a sieve through which the past slips. As her mother loses her grasp on their shared history, Elizabeth Kadetsky sifts through boxes of the snapshots, newspaper clippings, pamphlets, and notebooks that remain, hoping to uncover the memories that her mother is actively losing as her dementia progresses. These remnants offer the false yet beguiling suggestion that the past is easy to reconstruct—easy to hold. At turns lyrical, poignant, and alluring, The Memory Eaters tells the story of a family’s cyclical and intergenerational incidents of trauma, secret-keeping, and forgetting in the context of the 1970s and 1980s New York City. Moving from her parents’ divorce to her mother’s career as a Seventh Avenue fashion model and from her sister’s addiction and homelessness to her own experiences with therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder, Kadetsky takes readers on a spiraling trip through memory, consciousness fractured by addiction and dementia, and a compulsion for the past salved by nostalgia. From our contemporary vantage point, voice mail may seem like a quaint artifact of the ’80s and ’90s. But the answering machine was in fact preceded by a lesser-known era of voice messaging, one which began in the early 1900s and grew out of the phonograph. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, and before he unveiled the device to the public, he spent some time colliding morphemes in a notebook. He thought he might call his invention the “antiphone” (back-talker) or the “liguphone” (clear speaker), or perhaps the “bittakophone” (parrot speaker), “hemerologophone” (speaking almanac), or “trematophone” (sound borer). In the end, Edison settled on the straightforward “phonograph,” meaning “sound writer”—an efficient summary of its mechanism. The phonograph received vibrations from the air and transcribed them as calligraphy. Sound waves would cause a needle to quiver, and the needle would etch a continuous line on a turning cylinder. If you reversed the process, the needle would travel along the groove, mining sound from the uneven topography and playing it back through a horn.

From our contemporary vantage point, voice mail may seem like a quaint artifact of the ’80s and ’90s. But the answering machine was in fact preceded by a lesser-known era of voice messaging, one which began in the early 1900s and grew out of the phonograph. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, and before he unveiled the device to the public, he spent some time colliding morphemes in a notebook. He thought he might call his invention the “antiphone” (back-talker) or the “liguphone” (clear speaker), or perhaps the “bittakophone” (parrot speaker), “hemerologophone” (speaking almanac), or “trematophone” (sound borer). In the end, Edison settled on the straightforward “phonograph,” meaning “sound writer”—an efficient summary of its mechanism. The phonograph received vibrations from the air and transcribed them as calligraphy. Sound waves would cause a needle to quiver, and the needle would etch a continuous line on a turning cylinder. If you reversed the process, the needle would travel along the groove, mining sound from the uneven topography and playing it back through a horn. One might amplify the point: it is surprising that Hegel’s aesthetic has suffered neglect in our own postmodern age, so-called, when the preeminence of the aesthetic is so marked, to the diminution of the religious, and the sterilization of the philosophical in its high idealistic ambitions. In the quarrel between the poets and the philosophers, the post-Nietzscheans have decided in favor of the poets, and one might expect the richness of Hegel’s aesthetics to be accorded some honorable place in that context. Perhaps the neglect reflects the fact that in the end Hegel places philosophy in an ultimate position in absolute spirit, and indeed seems to place the absolute spiritual significance of the aesthetic behind us. There is an element of discordance with Hegel’s proclamation of the end of art in a time when art seems to have displaced the religious in the lists of spiritual ultimacy, and philosophy itself has contented itself with being more or less an academic specialty, whether of an analytical or hermeneutical sort. Hegel is discordant in that post-Hegelian culture has tended to place in art high hopes for a suitable replacement of lost religious transcendence. It is notable even among philosophers at least in the continental tradition, that art has assumed unprecedented (sometimes metaphysical) significance: Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Adorno, Merleau-Ponty, Badiou, to name some.

One might amplify the point: it is surprising that Hegel’s aesthetic has suffered neglect in our own postmodern age, so-called, when the preeminence of the aesthetic is so marked, to the diminution of the religious, and the sterilization of the philosophical in its high idealistic ambitions. In the quarrel between the poets and the philosophers, the post-Nietzscheans have decided in favor of the poets, and one might expect the richness of Hegel’s aesthetics to be accorded some honorable place in that context. Perhaps the neglect reflects the fact that in the end Hegel places philosophy in an ultimate position in absolute spirit, and indeed seems to place the absolute spiritual significance of the aesthetic behind us. There is an element of discordance with Hegel’s proclamation of the end of art in a time when art seems to have displaced the religious in the lists of spiritual ultimacy, and philosophy itself has contented itself with being more or less an academic specialty, whether of an analytical or hermeneutical sort. Hegel is discordant in that post-Hegelian culture has tended to place in art high hopes for a suitable replacement of lost religious transcendence. It is notable even among philosophers at least in the continental tradition, that art has assumed unprecedented (sometimes metaphysical) significance: Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Adorno, Merleau-Ponty, Badiou, to name some. When he set out to investigate the inner world of exotic animal breeders, Eric Goode had no idea he would end up making the hit Netflix series

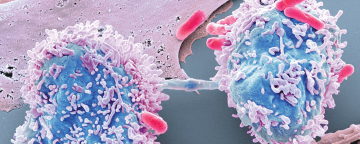

When he set out to investigate the inner world of exotic animal breeders, Eric Goode had no idea he would end up making the hit Netflix series  In the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, a team of scientists is shrunk to fit into a tiny submarine so that they can navigate their colleague’s vasculature and rid him of a deadly blood clot in his brain. This classic film is one of many such imaginative biological journeys that have made it to the big screen over the past several decades. At the same time, scientists have been working to make a similar vision a reality: tiny robots roaming the human body to detect and treat disease.

In the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, a team of scientists is shrunk to fit into a tiny submarine so that they can navigate their colleague’s vasculature and rid him of a deadly blood clot in his brain. This classic film is one of many such imaginative biological journeys that have made it to the big screen over the past several decades. At the same time, scientists have been working to make a similar vision a reality: tiny robots roaming the human body to detect and treat disease. For authoritarian-minded leaders, the coronavirus crisis is offering a convenient pretext to silence critics and consolidate power. Censorship in China and elsewhere has fed the pandemic, helping to turn a potentially containable threat into a global calamity. The health crisis will inevitably subside, but autocratic governments’ dangerous expansion of power may be one of the pandemic’s most enduring legacies.

For authoritarian-minded leaders, the coronavirus crisis is offering a convenient pretext to silence critics and consolidate power. Censorship in China and elsewhere has fed the pandemic, helping to turn a potentially containable threat into a global calamity. The health crisis will inevitably subside, but autocratic governments’ dangerous expansion of power may be one of the pandemic’s most enduring legacies. Science costs money. And for a brief, glorious period between the start of the Manhattan Project in 1939 and the cancellation of the Superconducting Super Collider in 1993, physics was awash in it, largely sustained by the Cold War. Things are now different, as physics — and science more broadly — has entered a funding crunch. David Kaiser, who is both a working physicist and an historian of science, talks with me about the fraught relationship between scientists and their funding sources throughout history, from Galileo and his patrons to the current rise of private foundations. It’s an interesting listen for anyone who wonders about the messy reality of how science gets done.

Science costs money. And for a brief, glorious period between the start of the Manhattan Project in 1939 and the cancellation of the Superconducting Super Collider in 1993, physics was awash in it, largely sustained by the Cold War. Things are now different, as physics — and science more broadly — has entered a funding crunch. David Kaiser, who is both a working physicist and an historian of science, talks with me about the fraught relationship between scientists and their funding sources throughout history, from Galileo and his patrons to the current rise of private foundations. It’s an interesting listen for anyone who wonders about the messy reality of how science gets done. On Friday, March 20, I called my father to congratulate him on the Persian New Year. It felt gloomy, to put it mildly. We used to do it in person, shaking hands, hugging, and the three traditional kisses on the cheeks. As we are in self-quarantine, 300 miles away from each other, he acquired his very first smartphone just a week ago, rapidly catching up with technology to keep in touch with me. I watched him as he tried to turn on the selfie camera. He kept the phone so close that I could only see him with difficulty. But I could observe parts of him that usually go unnoticed: details of the wrinkles on his face, the tears he was struggling to hold back, a bruise on his left cheek, speckles I hadn’t seen before. We talked for a while, five minutes maybe, the longest routine call we had in years, and then we retreated into solitude, each into his own. The whole episode reminded me of stories of families torn apart by immigration. We are now torn apart by another, equally invisible force.

On Friday, March 20, I called my father to congratulate him on the Persian New Year. It felt gloomy, to put it mildly. We used to do it in person, shaking hands, hugging, and the three traditional kisses on the cheeks. As we are in self-quarantine, 300 miles away from each other, he acquired his very first smartphone just a week ago, rapidly catching up with technology to keep in touch with me. I watched him as he tried to turn on the selfie camera. He kept the phone so close that I could only see him with difficulty. But I could observe parts of him that usually go unnoticed: details of the wrinkles on his face, the tears he was struggling to hold back, a bruise on his left cheek, speckles I hadn’t seen before. We talked for a while, five minutes maybe, the longest routine call we had in years, and then we retreated into solitude, each into his own. The whole episode reminded me of stories of families torn apart by immigration. We are now torn apart by another, equally invisible force.

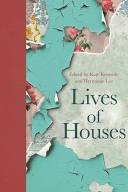

My favourite essay, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst’s ‘At Home with Tennyson’, is both a bravura work of close reading and a highly sensitive study of the poet’s loyalties, yearnings and fears about homes and homelessness. Tennyson, he demonstrates, was profoundly touched by the idea of home and ‘was equally good at evoking home when it existed only as an idea, as in “The Lotos-Eaters”, where so much of what the speaker broods over – “roam”, “foam”, “honeycomb” – has the word “home” flickering through it like a nagging but elusive memory’. Douglas-Fairhurst is yet another of the essayists here to be attracted by the word ‘nest’: Tennyson produces a ‘voice that is keen to create a nest of words for itself but also appears to be nervously eyeing up the lines of each stanza like a little set of prison bars’. This is criticism that draws quite close to the status of poetry.

My favourite essay, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst’s ‘At Home with Tennyson’, is both a bravura work of close reading and a highly sensitive study of the poet’s loyalties, yearnings and fears about homes and homelessness. Tennyson, he demonstrates, was profoundly touched by the idea of home and ‘was equally good at evoking home when it existed only as an idea, as in “The Lotos-Eaters”, where so much of what the speaker broods over – “roam”, “foam”, “honeycomb” – has the word “home” flickering through it like a nagging but elusive memory’. Douglas-Fairhurst is yet another of the essayists here to be attracted by the word ‘nest’: Tennyson produces a ‘voice that is keen to create a nest of words for itself but also appears to be nervously eyeing up the lines of each stanza like a little set of prison bars’. This is criticism that draws quite close to the status of poetry. The biopharmaceutical industry will be able to make a Covid-19 vaccine— probably a few of them—using various existing vaccine technologies. But many people worry that Covid-19 will mutate and evade our vaccines, as the flu virus does each season. Covid-19 is fundamentally different from flu viruses, though, in ways that will allow our first-generation vaccines to hold up well. To the extent that Covid does mutate, it’s likely to do so much more slowly than the flu virus does, buying us time to create new and improved vaccines. Every virus has a genome composed of genetic material (either RNA or DNA) that encodes instructions for replicating the virus. When a virus infects a cell, it accesses machinery for making copies of its genomic instructions and follows those instructions to make viral proteins that assemble, with copies of the instructions, to form more viruses (which then pop out of the cell to infect new cells, either in the same host or in someone new). There is a critical difference between coronaviruses and flu. The novel coronavirus genome is made of one long strand of genetic code. This makes it an “unsegmented” virus—like a set of instructions that fit on a single page. The flu virus has eight genomic segments, so its code fits on eight “pages.” That’s not common for viruses, and it gives the flu a special ability. Because the major parts of the flu virus are described on separate pages (segments) of its genome, when two different flu viruses infect the same cell, they can swap pages.

The biopharmaceutical industry will be able to make a Covid-19 vaccine— probably a few of them—using various existing vaccine technologies. But many people worry that Covid-19 will mutate and evade our vaccines, as the flu virus does each season. Covid-19 is fundamentally different from flu viruses, though, in ways that will allow our first-generation vaccines to hold up well. To the extent that Covid does mutate, it’s likely to do so much more slowly than the flu virus does, buying us time to create new and improved vaccines. Every virus has a genome composed of genetic material (either RNA or DNA) that encodes instructions for replicating the virus. When a virus infects a cell, it accesses machinery for making copies of its genomic instructions and follows those instructions to make viral proteins that assemble, with copies of the instructions, to form more viruses (which then pop out of the cell to infect new cells, either in the same host or in someone new). There is a critical difference between coronaviruses and flu. The novel coronavirus genome is made of one long strand of genetic code. This makes it an “unsegmented” virus—like a set of instructions that fit on a single page. The flu virus has eight genomic segments, so its code fits on eight “pages.” That’s not common for viruses, and it gives the flu a special ability. Because the major parts of the flu virus are described on separate pages (segments) of its genome, when two different flu viruses infect the same cell, they can swap pages. The coronavirus pandemic has brought chaos to lives and economies around the world. But efforts to curb the spread of the virus might mean that the planet itself is moving a little less. Researchers who study Earth’s movement are reporting a drop in seismic noise — the hum of vibrations in the planet’s crust — that could be the result of transport networks and other human activities being shut down. They say this could allow detectors to spot smaller earthquakes and boost efforts to monitor volcanic activity and other seismic events. A noise reduction of this magnitude is usually only experienced briefly around Christmas, says Thomas Lecocq, a seismologist the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Brussels, where the drop has been observed. Just as natural events such as earthquakes cause Earth’s crust to move, so do vibrations caused by moving vehicles and industrial machinery. And although the effects from individual sources might be small, together they produce background noise, which reduces seismologists’ ability to detect other signals occurring at the same frequency.

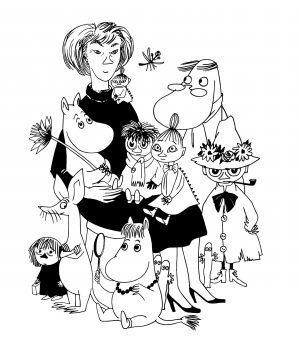

The coronavirus pandemic has brought chaos to lives and economies around the world. But efforts to curb the spread of the virus might mean that the planet itself is moving a little less. Researchers who study Earth’s movement are reporting a drop in seismic noise — the hum of vibrations in the planet’s crust — that could be the result of transport networks and other human activities being shut down. They say this could allow detectors to spot smaller earthquakes and boost efforts to monitor volcanic activity and other seismic events. A noise reduction of this magnitude is usually only experienced briefly around Christmas, says Thomas Lecocq, a seismologist the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Brussels, where the drop has been observed. Just as natural events such as earthquakes cause Earth’s crust to move, so do vibrations caused by moving vehicles and industrial machinery. And although the effects from individual sources might be small, together they produce background noise, which reduces seismologists’ ability to detect other signals occurring at the same frequency. In the nineteen-fifties and sixties, one of the most famous cartoonists in the world was a lesbian artist who lived on a remote island off the coast of Finland. Tove Jansson had the status of a beloved cultural icon—adored by children, celebrated by adults. Before her death, in 2001, at the age of eighty-six, Jansson produced paintings, novels, children’s books, magazine covers, political cartoons, greeting cards, librettos, and much more. But most of Jansson’s fans arrived by way of the Moomins, a friendly species of her invention—rotund white creatures that look a little like upright hippos, and were the subject of nine best-selling books and a daily comic strip that ran for twenty years.

In the nineteen-fifties and sixties, one of the most famous cartoonists in the world was a lesbian artist who lived on a remote island off the coast of Finland. Tove Jansson had the status of a beloved cultural icon—adored by children, celebrated by adults. Before her death, in 2001, at the age of eighty-six, Jansson produced paintings, novels, children’s books, magazine covers, political cartoons, greeting cards, librettos, and much more. But most of Jansson’s fans arrived by way of the Moomins, a friendly species of her invention—rotund white creatures that look a little like upright hippos, and were the subject of nine best-selling books and a daily comic strip that ran for twenty years.